By Gabriel Sanchez

In recent months, the crisis surrounding Florida coastlines and the Everglades has exploded into the national spotlight. Stories of algae filled waters, massive fish kills, and seagrass die off have haunted Floridians. Fortunately, scientists like Dr. Mark Butler, Elliot Hart, and Jack Butler are pioneering sponge studies that could have positive implications for restoring nearshore waters.

Currently, the inshore waters of the bay, near Marathon and Pigeon Key, are home to four nurseries, home to 4,000 sponges. Project coordinators plan to expand the project to 15,000 sponges. To accomplish this, the scientists have taken advantage of the sponge’s biology, using fragmentation, much like Mote Marine in the Lower Keys is using fragmentation processes to grow coral faster and stronger.

“Sponges act as nursery for stone crab, lobster, finfish, and provide shelter for these species,” said Elliot Hart, an ecologist with the Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC). “These species aren’t the only ones who depend on sponges to thrive though. The interior the sponges are where species of sea worms, arthropods, and most importantly, snapping shrimp live.”

In addition to the FWC, the project includes input from the Florida Sea Grant, a university-based research foundation, and Old Dominion University of Virginia.

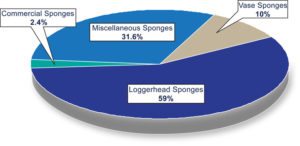

Hart said 30 to 40 percent of the sea floor surrounding the Florida Keys is hard bottom, comprised of mostly limestone with a thin layer of sand. These hard bottoms are typically home to several main species of sponges. With algae blooms and its subsequent effect on coastal waters, the sponges are dying. That’s significant because shellfish and finfish rely on the sponge habitat.

One of the Key players in the sponge habitat are the snapping shrimp. No bigger than grains of rice, the shrimp have sophisticated social systems, complete with a queen and working shrimp. The shrimp emit a sound that scientists believe sends a signal to other species about the health of the habitat.

“If you’ve ever been in the water and heard crackling or barely audible clicking sounds, those could be snapping shrimp you are hearing,” said Hart.

Many of the concepts and their pilot studies were pioneered by Dr. Mark Butler professor of Department of Biological Sciences of Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. Dr. Butler developed techniques for studying sponge fragmentation that FWCC ecologists currently employ. He’s scheduled to visit the Keys and continue his research this month.

Jack Butler, of FWCC, studied ecological sciences under Dr. Mark Butler at Old Dominion University and, six years later, finds himself continuing research on the topic. “In 2010, Dr. Butler started the first feasibility studies with three species commonly found in the bay. Florida Sea Grant is coordinating volunteers to get locals involved,” said Butler. Butler said he looks forward to his former professor, turned colleague, visiting and continuing research.

The process of fragmentation may sound easy enough: cut the sponges into pieces, zip tie them to a brick, and implant them in favorable conditions. However, the number of cuts, the angle of the cuts, and water temperature have all been determined to play a role in the regeneration process, Hart said.

Studies conducted this month will include placing in two locations of a running water system. At one end, levels of chlorophyll and cyanobacteria will measured in the Bay; further downstream, levels will be measured again.

“We’re also looking to see what the optimal density of sponges is to best supplement natural recruitment. Having healthy sponges ready in the nurseries can benefit areas needing it after algae blooms like we’ve recently seen,” said Hart.

—–

What’s that sound?

Snorkelers and divers often hear a crackling or barely audible clicking. The sound, scientists say, is produced by snapping shrimp found in sponge habitats.