Oceanfront properties have always been the most coveted parcels in the Florida Keys and not just because of the unobstructed views. In the pioneer days, before the age of in-home air-conditioning and government-funded mosquito control, ocean breezes were welcomed as both a cooling device and a rudimentary form of pest control. When Israel Lafayette Jones bought Porgy Key in the summer of 1897, one of the reasons the 63-acre island was affordable ($300) was because the mangrove-ringed island is mostly tucked behind Old Rhodes Key. Jones cleared land and planted commercial crops of pineapples and lime trees.

Porgy Key was not the only island he purchased; he eventually acquired Old Rhodes and Totten keys. The birth of his first son, King Arthur Lafayette Jones, would coincide with the purchase of his first island. The 1898 birth of his second son, Sir Lancelot Garfield Jones, occurred the same year he purchased his second island. Just as their father did back in North Carolina, the two boys grew up working in the fields. A primary difference, in this case, was that their father had more than likely been born to slaves, and Arthur and Lancelot had been born to a man in the middle of fulfilling the American dream.

Their initial schooling was provided by a tutor who was brought to Porgy Key. Later, the boys traveled to St. Augustine, where they continued their education at the Florida Baptist Academy, a school their father helped bring to fruition. Eventually, the school would move to Miami and is today recognized as Florida Memorial University. Arthur and Lancelot would become formally trained as a carpenter and mason before coming back to the family farms, which could now be found on Porgy, Old Rhodes and Totten keys.

When they were not working in the fields, as they had since they were boys, the two fished the local waters, perfecting techniques for catching, among other species, bonefish. Their childhood passion led them to learn every nook and cranny of the northern Keys, an education that would serve them for the rest of their lives.

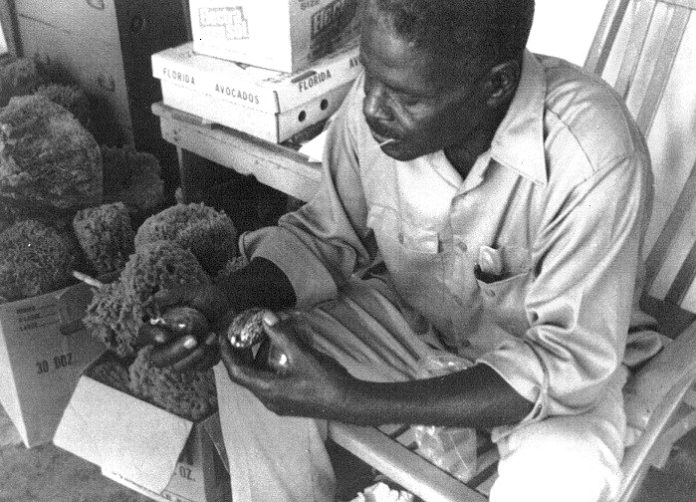

On Totten Key, the family developed a 50-acre lime grove. They created a “rail” system of 2×4 tracks that traveled between the fields and the packing house. To make shipping easier, they carved a trench that led away from the island, through the shallows, and out to the nearest creek. When the limes were producing, the trench made it possible for the Joneses to ship 250 barrels of limes to Miami every week. The family farms made the Joneses one of the largest independent producers of limes in the state.

Like the 1906 Hurricane that devastated the pineapple industry, two future hurricanes would eventually end the Joneses’ lime groves. The 1926 Great Miami Hurricane delivered a massive blow to South Florida and the northern Keys. The Joneses’ lime fields were no exception. Fortunately for Lancelot and Arthur, they were skilled fishermen who knew the local waters as well as they knew each other. In addition to catching fish for sport, the brothers fished commercially, harvesting lobster and stone crab they supplied to the Cocolobo Cay Club built on Adams Key by Carl Fisher in 1921. In 1935, Lancelot began working as a fishing guide for Fisher’s private club. On Sept. 2, Labor Day, the most powerful hurricane ever to strike North America (to this day) struck the Upper Keys.

The Category 5 storm marked the beginning of the end of the Joneses’ farming days, and by 1938 they had left their farming days behind them and began working more steadily as fishermen. Lancelot, guiding for members of the Cocolobo Cay Club, among others, would fish more than his fair share of presidents as well as other people of influence. Listed among them was Daniel Topping, once owner of the New York Yankees, and presidents Herbert Hoover, Lyndon B. Johnson, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon.

King Arthur Lafayette Jones died in 1966. His younger brother would live significantly longer and continue to live a storied life of his own that would include playing a part in the creation of Biscayne National Park. Lancelot and his sister-in-law would sell more than 277 acres of their land to the National Park Service in 1970 for $1.2 million, a transaction that included Lancelot’s island home, Porgy Key. An amendment to the sale was that Lancelot would be able to continue to live in his family home on Porgy Key. In 1992, Hurricane Andrew, a Category 5 storm, was bearing down on South Florida. Lancelot, age 94 at the time, refused to leave his home and had to be evacuated from Porgy Key. The storm destroyed Lancelot’s home.

Sir Lancelot Garfield Jones would live the remainder of his years in Miami. He passed away in 1997, at the age of 99. The Joneses’ property was declared the Jones Family Historic District on Oct. 23, 2013. Not much more than the concrete foundation of their former residence is visible today, plus a plaque providing a brief history of the site that anyone who wanders up can read. Clearly, it is a story worth telling over and over.