Even before Florida became a U.S. territory, Spain’s government tried to give away the largely uninhabited frontier land. In the Spanish territorial years, these efforts were called Spanish Land Grants. After the territory became a U.S. possession, President Abraham Lincoln passed the Homestead Act of 1862. The act allowed any U.S. citizen, or potential citizen, who was either over 21 years of age or who was the head of a household, be it man, woman, immigrant, or freed enslaved person, the ability to claim a parcel of undeveloped and unclaimed land from the public domain.

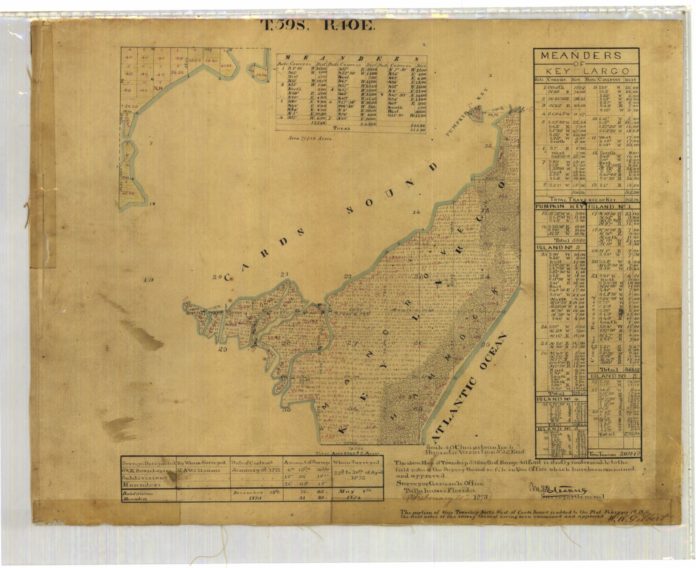

A small fee was required to secure the rights to relatively large swaths of United States soil. In addition, a great deal of sweat equity was necessary. Before a claim could be considered, the land had to be surveyed by a U.S. representative. In the Florida Keys, land surveys began in 1872. The accompanying image is a copy of the original survey conducted by M.A. Williams, whom the government contracted on Jan. 2, 1872, to do survey work. This land survey on North Key Largo and Pumpkin Key, part of Township 59 South of Range 40 East, was conducted between April 22 and April 30, 1872.

The following steps were taken to make a homestead claim. First, a claimant went to the nearest Land Office and filed a claim. The agent then checked the records for any prior claims of ownership. Providing no claims existed, a $10 filing fee was paid to secure the rights to the land. The land agent was paid a $2 commission.

From that point forward, it was up to the homesteader to chip in with the sweat equity end of the deal. The homesteader’s job was to improve the property by clearing the land, producing some kind of crop through farming, and building a home or other dwelling that measured at least 12 feet by 14 feet. Time also had to be spent living on the property. After clearing the land, building a home and spending five years living on the property, the homesteader could file a claim for the land’s title.

In order to receive clear title to the land, an affidavit was filed stating that the homesteader had spent five years living on the property. The document was a standardized, fill-in-the-blank, piece of paper that read, in part: “That the said __ entered upon and made settlement on said land on the __ day of __, 18__ and has built a house thereon __ and has lived in the said house and made it his exclusive home from the __ day of __, 18__ to the present time, and that he has since said settlement ploughed, fenced, and cultivated about __ acres of said land, and has made the following improvements thereon to wit.”

The affidavit was then signed by two neighbors or friends willing to vouch that the homesteader had fulfilled the obligations. Once both witnesses had signed and dated the document, there was one last piece of business. A final $6 payment to the land agent had to be made.

However, this was not the only way to make a homestead claim.

For those individuals that did not want to live on the land for the full five years, the acquisition process could be expedited by paying a fee of $1.25 per acre. A clear title could be procured by living on the land for only six months for those choosing to go this route. The affidavit, signed by two neighbors willing to vouch for the homesteader’s residency, still had to be filled out and filed.

In either case, for the homesteader’s effort, he received a clear deed, or land patent, to his property that the president of the United States signed. While it is sometimes hard to imagine the island chain’s early pioneers as farmers, many Florida Keys homesteaders produced crops to help feed their families and neighbors. They also produced cash crops.

The Key West column of the Dec. 27, 1884 Fort Myers Press stated: “Many of the leading merchants own tracts of land on the Keys which are entirely devoted to the culture of pineapples, tomatoes, Irish potatoes, sweet potatoes, cabbage, cassava, tapias, beets, carrots, turnips and various tropical fruits which flourish in abundance. The average shipments of pineapples alone will reach more than $200,000 per annum.”

On June 20, 1885, the newspaper again stated: “The best melons for this season come from Key Largo.”