Sun-baked Keys residents suffering through “feels-like” temperatures well north of 100 degrees, with nearshore waters that feel more like jacuzzis, aren’t the only ones issuing a cry for help – the Keys’ coral reefs aren’t far behind.

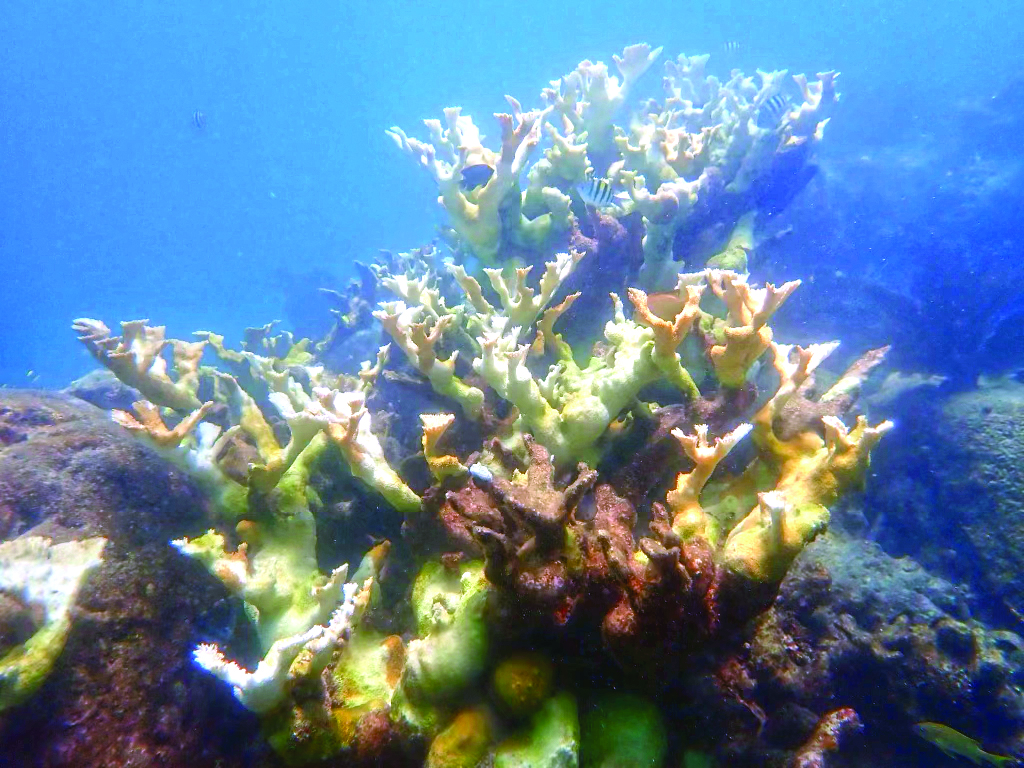

Coral bleaching is a phenomenon that occurs when polyps under stress from a variety of factors, including heat, expel the algal cells (zooxanthellae) that give them their color and provide energy for the coral in a symbiotic relationship. Though bleached corals may survive for short periods of days or a few weeks without re-uptake of the algal cells, without the photosynthetic byproducts that provide the corals with the majority of their energy, they largely lose their ability to feed themselves and protect against other stressors, significantly upping their mortality if stressors continue over a prolonged period.

With bleaching commonly seen in Keys coral species when water temperatures reach a consistent 30.5 degrees Celsius (roughly 87 degrees Fahrenheit), some degree of the phenomenon has become relatively common, in limited quantities, during the sweltering late-summer months.

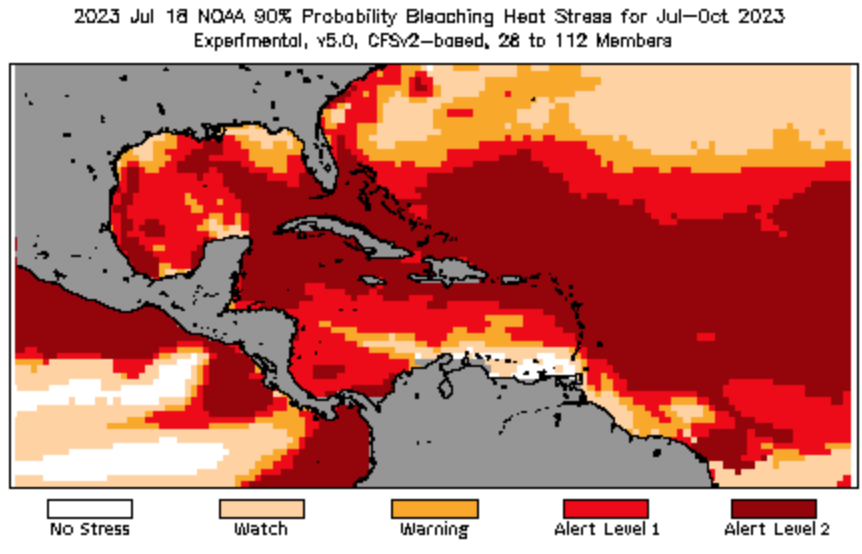

In 2023, it’s already happening. As of July 18, NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch upgraded Florida Keys waters from Alert Level 1 to Alert Level 2, indicating a 90% probability of bleaching heat stress for the months of July through October. And as several restoration practitioners diving the reefs every day have reported, the effects are already visible.

“We have already observed severe temperature-related bleaching and disease at Sombrero Reef and eastern Dry Rocks, and other practitioners have reported mild bleaching and disease at Looe Key,” said Phanor Montoya-Maya, restoration program manager for Coral Restoration Foundation.

“The fact that we are getting this already, and there are no storms on the horizon, is terrifying,” added Kylie Smith, vice president of I.CARE, a community-based reef restoration and conservation organization. While shallow nearshore waters already feel like a bathtub, she said reefs at 50 to 60 feet deep are already approaching 90-degree temperatures.

“Last year we started to see paling and some partial bleaching, but it wasn’t until September,” she said. “Hurricane Ian came at the end of September and knocked the temperatures down, and bleaching subsided.”

Mote president and CEO Michael Crosby went a step further. Speaking with the Keys Weekly on July 18, he called the temperature stress and resulting bleaching “absolutely one of the single most challenging threats that there are to the continued survival of reefs around the world.”

PUMPING THE BRAKES

With more than a dozen organizations and agencies heavily involved in reef restoration and protection via coral outplanting throughout the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), the stressful temperatures are, in some cases, challenging practitioners to strike a balance between survivorship and outplanting quotas that form the basis for critical grant funding.

Some have already chosen to impose a temporary voluntary moratorium on outplanting activities, as representatives for I.CARE, CRF and Reef Renewal USA confirmed.

“We’re hoping that granting agencies and stakeholders are going to understand that this is the best course of action for the corals and for our ultimate goals, which is restoring the reef,” Reef Renewal USA operations manager Kevin Macaulay told the Weekly. “Putting all these beautiful corals we’ve spent a year and a half growing out on the reef right now, just to watch them die, is not the answer.”

Speaking to the Weekly on July 17, FKNMS superintendent Sarah Fangman said the sanctuary has yet to issue a complete formal moratorium on outplanting activities. However, sanctuary staff are in the process of working with FWC to finalize language that would guide updated management practices and compel permitted stakeholders in the sanctuary and throughout Florida to cease certain activities – including outplanting for certain purposes – during periods when water temperatures exceed 30.5 degrees C. With the agencies’ most recent meeting on July 18, these guidelines could be handed down in a matter of days or weeks.

“Many practitioners are stopping on their own,” she said. “They want as much as you and I for these corals to thrive and survive, and they know that outplanting right now is a risky endeavor. … It’s going to be bad. It’s just, how bad is it going to be?

“I will say that there is a potential for outplanting to continue for the purposes of science to understand the genotypes that are more or less resilient to these conditions. … Practitioners could ask for, and receive, permission to continue with the intention not of just planting corals, but for the purpose of understanding.”

BUILDING THE BANK – ‘NOAH’S ARK’ FOR CORALS

As native coral species, seven of which are endangered, continue to stare down such a strong threat, one piece of the preservation and restoration puzzle lies in two land-based coral gene banks: one at Mote Marine Lab’s Sarasota facility, and another at The Reef Institute in West Palm Beach.

Jennifer Moore is the protected-coral recovery coordinator for the National Marine Fisheries Service. Tasked with overseeing the recovery of iconic endangered species like elkhorn and staghorn corals, she outlined the goal of what Fangman called a “Noah’s Ark” for about 150 and 300 unique remaining genotypes of elkhorn and staghorn coral, respectively.

“To prevent the full loss of the very few remaining unique individuals that we have across the two species (staghorn and elkhorn), we are collecting two fragments from each unique individual,” she said. “Each of those facilities will have a full complement of all of the living elkhorn and staghorn coral that we have in Florida, in case things get really bad as they’re predicted to in the wild.”

The process is similar to collection efforts initiated by the state and NOAA in response to 2014’s deadly outbreak of stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD), resulting in the safe stockpiling of more than 2,000 individual corals across 16 native species in land-based zoos and aquariums throughout the country. As Moore pointed out, the “good news and bad news” is that “we already had that done prior to this heat wave, so we didn’t have to focus on those species.”

“We’re fortunate in this community that it’s always all-hands-on-deck when we have these types of situations,” she added, noting the contributions of partners like the Florida Aquarium, Mote, CRF, Reef Renewal, the University of Miami and Nova Southeastern University alongside the work of federal employees. “When the need arises, they drop everything and respond. All these institutions deserve an amazing amount of credit in making this successful.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

As critical reef species face constant attacks from human impacts, SCTLD, ocean acidification and heat-induced bleaching, continued work by all involved to identify, and aid in the reproduction of, resilient genotypes remains a perpetual item atop researchers’ wish lists. Crosby told the Weekly he feels confident in Mote’s science-based approach that identifies hardy individuals – and their degree of resilience – from some 8,000 different genotypes of native species.

Macaulay echoed Crosby’s sentiments. “Everybody is focused now on trying to learn from this event,” he said. “We believe that the corals of tomorrow don’t exist today. If one or two corals make it through this event unbleached, those are the ones we’re going to work with in the future.”

And while existing gene banks are part of the picture as an important failsafe, Fangman also stressed a need to create a “deeper toolbox” for practitioners to adapt to varying yearly threats.

“We’re starting to try to figure out what that would look like,” she said. “Is it shading? Is it moving certain nursery stock out into deeper, cooler water? … All of them are complex, but we need to start piloting those so we can understand what else we can do besides wring our hands and watch.”

BECOME PART OF THE SOLUTION

The Florida Keys’ BleachWatch Program, modeled after Great Barrier Reef’s BleachWatch, is a team of trained recreational, commercial and scientific divers who help monitor and report on conditions at the reefs. After each visit to the reef, the divers complete a data form, either printed or online, and send it to the BleachWatch coordinator. Visit www.mote.org/bleachwatch for more information and online training. In-person training workshops are expected to be announced soon at Mote and in the Upper Keys.

Jim McCarthy contributed to this report.