Amid concerns with occupants and rents in Marathon’s affordable housing developments, city housing coordinator and real estate agent Josh Mothner delivered an affordable housing master class to fill the Marathon City Council’s Oct. 22 workshop.

Recent discourse in council sessions and on social media has questioned advertised rents for Marathon’s newest affordable housing developments, specifically targeting Coco Plum Drive’s CoCo Vista apartments. Debate has intensified over the last month as the city council approved ordinances providing a mechanism for the potential transfer of unused affordable housing allocations from other jurisdictions for future use in Marathon.

Profiling the city’s housing landscape, Mothner said the median price for dry lot single-family homes on the market today in Marathon is $792,500. One of the lowest-priced units, a $529,000 townhome in the Sisters Creek development between 24th and 25th streets, would require a new homeowner to furnish about $48,000 at closing to obtain an FHA home loan by providing a 3.5% down payment, followed by a $4,344 monthly payment. A more traditional 20% down payment on the same home would require roughly $135,500 in up-front costs, with a monthly payment of $3,628.

Either scenario, Mothner said, simply isn’t a reality for a large portion of Marathon’s workforce.

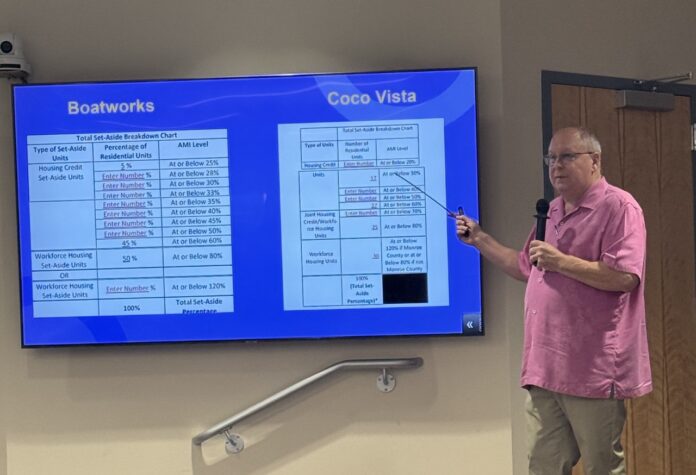

Several affordable housing projects throughout the city, including highly-publicized projects like 39th Street’s Boatworks and CoCo Vista, among others, utilize federally-offered Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) to offset losses incurred when affordable units are constructed and rented at capped rates to tenants whose incomes fall below certain percentages of Monroe County’s median salary of $97,500.

Of the 109 CoCo Vista units, 17 are reserved for tenants at or below 30% of the median income, with 37 reserved for 60% earners, 25 reserved for 80% earners and 30 available for residents making up to 120% of the median income.

Using rates and income limits released by the Florida Housing Finance Corporation based on U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) numbers, a two-person household making less than $28,620 in total would qualify for a 30% unit, capping the monthly rate at $805 per month for a two-bedroom apartment. The same pair earning up to $114,480 in combined income (120% of the median) could theoretically pay up to $3,222 for the same two-bedroom unit. A 1-bedroom apartment rented by a single 120% earner (with a max salary of $100,320) could go for up to $2,685 per month.

While the high-end rental rates have been a source of recent debate, Mothner said the soaring rates are a symptom of an older problem Marathon faced less than a decade ago.

“We tend to look at things in snapshots – what’s going on in front of us at the moment,” he said, citing the work of a 2015 city task force that put affordable housing under the microscope at a time when housing projects could only qualify for tax credits if they rented to tenants under 60% of the median income.

“At that time, the argument was that the cop, or the teacher, could make too much money to qualify for those units,” he said, adding that city officials petitioned the state to allow higher earners at 80%, 100% or 120% of the median income to qualify for the rent-capped units. At the same time, each resident leaving Marathon who fell below the median income caused that median – and the corresponding maximum affordable rental rates – to rise.

“I want you to understand that that change – going to 80% and 120% – in conjunction with the incredible rise in median income, is what has caused what we have right now, which are rents that are driving people insane,” he said. However, he added, several developments are forced to rent for less than their maximum allowable rents when such rates begin to exceed the market rates for privately-offered rental properties.

“Just because you see something in the listing, doesn’t mean that that’s what the tenant is going to actually pay,” he said.

Mothner also addressed criticisms that affordable developments provided weekend escapes for mainland occupants, or that certain applicants on a wait list were being “pushed” to the front of the line for an available unit.

Profiling three projects with 159 total units, Mothner said there were 212 residents who qualified under the units’ income requirements, including eight tenants who qualified on disability income and eight on retirement income.

“If you look at the total, that’s 196 people in the workforce who aren’t disabled or retired, plus children, family members and other dependents,” he said. “That’s a pretty good percentage.”

Acknowledging that there was no way to guarantee every single unit was used properly at all times, Mothner said the risk to developers would far outweigh the benefit of renting to the wrong tenants.

“LIHTC projects are monitored by third-party auditors, because the tax credit portions of those projects involve millions of dollars,” he said. “If they blow it, and they’re renting to the wrong people at the wrong rents, they can lose millions of dollars, and lawsuits forever.”

Additionally, he said, if a low-income unit – think 30% or 60% – becomes available in a development, managers may be required to look further down their growing wait lists to find a tenant who qualifies.

“The first person in line isn’t necessarily going to get it,” Mothner said. “It’s possible that somebody that was 40th on the list could end up getting the next unit, because they’re the only ones who qualify. That’s something we need to understand.”

Editor’s note: Mothner’s presentation is by far the most concise summary of affordable housing mechanisms in our community that I’ve seen in my 10 years here.