By Mike Howie

A young man sits in an empty playground, wearing headphones over the hood of his sweatshirt, his hands in the pocket of the hoodie. Nearby is a woman who has called the police. The woman says the man hasn’t done anything, but he makes her nervous.

The man, who has ignored the woman, also ignores a police officer’s attempts to communicate, seeming lost in whatever he hears on the headphones. Asked to show his hands, the man brings an angular silver object out of his sweatshirt pocket.

Now what?

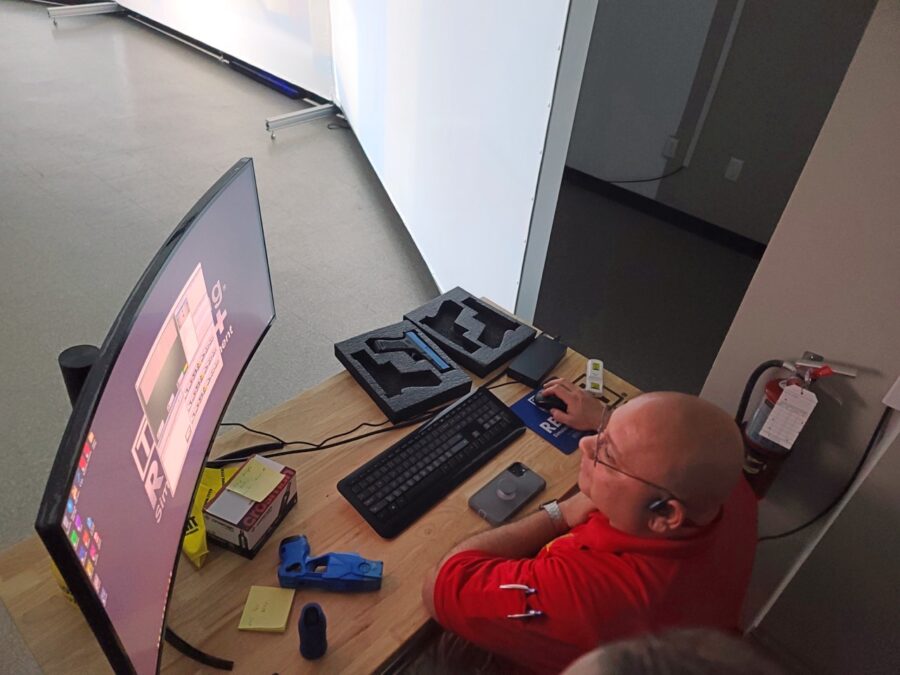

This situation played out recently at the Marathon headquarters of the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office. But it was on a large, panoramic video screen in a training room where, in one corner, Deputy Frank Westerband operated a computer that displayed the simulated scenario from the point of view of the officer.

Deputies in the county are getting advanced help in working through their possible reactions to a variety of scenarios, thanks to video simulation equipment that can reproduce a city street, a church, a bank lobby and more.

The equipment allows more deputies to be trained in less time, at lower cost and in more types of situations. Scenarios can be paused for discussion of specific moments. The operator can alter the responses of the on-screen characters.

Sheriff Rick Ramsay saw the system on display at a law enforcement conference.

“It can create any scenario you want,” he said, “on the water, on the land, on traffic, on a building search, in a school.”

The computer-driven simulation, based in Marathon and portable to the Upper and Lower Keys, uses one to three floor-to-ceiling screens that, joined together, produce a panoramic view. It features hundreds of situations.

“It allows deputies to decide when to use what type of force and why,” said Westerband.

One scenario, just seven seconds long, depicts a traffic stop. A woman driving the car has gotten out and is holding her license out.

That video helps train officers’ powers of observation, said Westerband. In the pocket of the open car door, a handgun is visible. The driver’s license is in a vertical format, which means the driver is under 21 – too young to own a handgun under Florida law. There is a passenger in the car.

Deputies need to absorb all those things quickly.

The scenario also allows a discussion of the legal situation. Is the gun stored properly? To whom does it belong? Is the driver under arrest?

Westerband will ask those questions, while reminding trainees about the driver: “She has rights.”

The trainees have electronic pistols, Tasers, shotguns and pepper spray, which all interact with the screen.

“We can see where the rounds are hitting,” Ramsay said. “Are they on target?”

Part of the training is about not using weapons at all, but helping deputies learn how to talk to people.

“The job (of being an officer) is a lot of listening and understanding,” Westerband said.

“We’re able to evaluate their verbal skills to de-escalate, command presence, decision-making,” Ramsay said.

In the scenario at the playground, Westerband said, the young man is on the autism spectrum. The park is a public place and he hasn’t broken any laws. The item he brings from his pocket is a toy. He is no threat.

The operator of the training has some control over how the characters react, even how they answer questions.

“Engaging with people, that’s a value of the system,” said Lt. Trevor Wirth, director of the training division and of school resource officers for MCSO. “You’re going to encounter difficult people.” The video training allows a deputy “to sit there and talk to a screen and teach yourself to keep your composure.”

The video simulation equipment, which cost about $145,000 in November, was paid for using money forfeited in drug cases. It has repaid much of its cost already, by reducing the use – and cost – of live ammunition and by reducing the time it takes to set up training scenarios.

It’s not the only training deputies receive, Wirth noted. They use a firing range in Marathon, which is large enough to be set up as a home or business. They are trained in driving under different situations. They have classroom sessions on how to write reports. Deputies also learn self-defense tactics – “You can’t really get that on a simulator,” he said.

While many officers praise the video training, Westerband finds that younger deputies take to it more easily – they’ve grown up interacting with video screens. Older officers tend to prefer live interaction, he said.

The training not only allows development of habits and reflexes, but also helps deputies “to talk about what we’re allowed to do,” Westerband said. “People think cops are able to do whatever they want.” While officers have leeway, “We have to follow the law. … The main thing is we are concerned about rights.”

“We don’t want to have our officers in a deadly-force situation,” Ramsay said, “but if they are in a deadly-force situation, they’ll more likely be successful and go home at the end of their shift to their families.”