It was windy on Boca Chica Beach and Florida Keys cold. A dark row of clouds looked as if it wanted to make good on a threat, and a man with keys hanging out of his maybe-too-short shorts told us the fighter jets weren’t flying that day, but, he continued, if you pointed a camera at the air base there was a good chance the MPs would come out and want to have a serious conversation.

We walked on a bit and I found myself apologizing to Duke Riley for the lack of trash.

Boca Chica Beach has traditionally been a wonderland of trash, not so much from the local litterati but from the offshore shipping lanes. Weird, unfamiliar bottles, bags and whatnot. I once found a hermit crab living in the cap of a shampoo bottle cap there. Another time there was a can of Glade air freshener with all the writing, except the logo, in Arabic. There used to be a whole section of fence decorated with all the unmatched shoes that had washed up – a sort of vernacular collective art installation.

But now there was hardly anything, detritus-wise, and since Riley’s current medium was trash – specifically plastic trash found on beaches – I felt I had oversold the place.

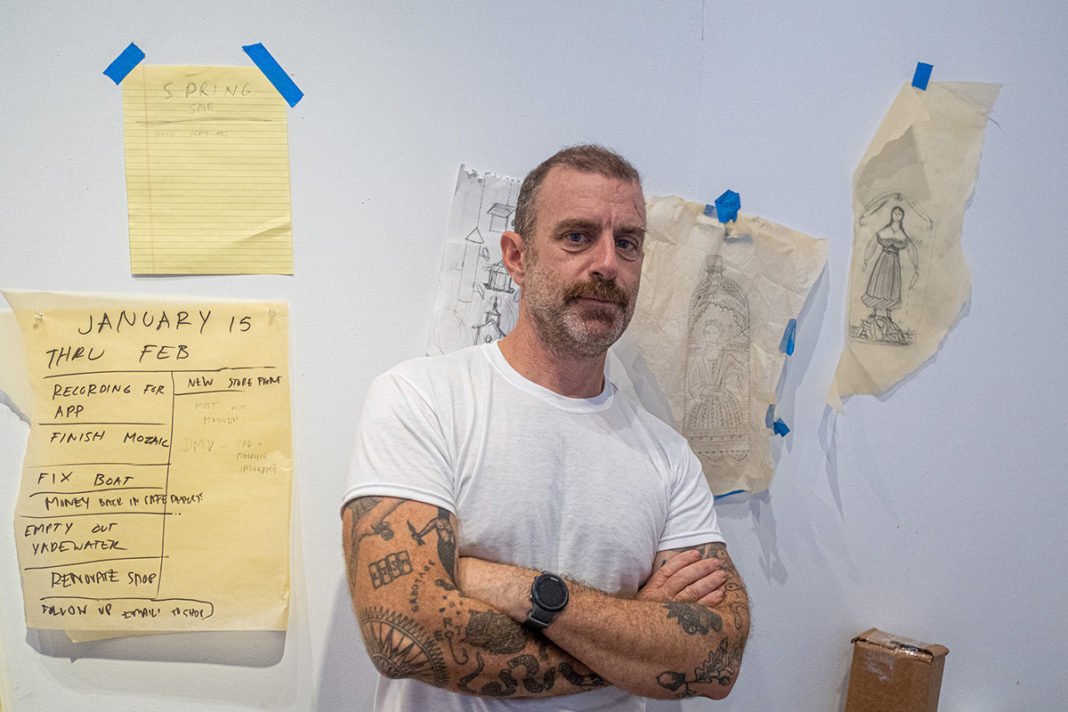

Riley, one of the artists-in-residence at The Studios of Key West this month, seemed less bothered than content to look. He’d brought a whole suitcase full of trash with him from New York. Anything we found would be a bonus. What he really wanted, he said, was the right piece of rope.

Riley had been making re-imagined seafarer crafts – scrimshaw pieces, cases of fishing lures, the intricately decorated octagonal boxes called sailors’ valentines. He was carving the scrimshaw onto items like painted dishwashing soap bottles and squirt guns.

“The old scrimshaw that you’d see on whales’ teeth would normally depict sea captains and ship owners and people like that. I’m doing pictures of lobbyists and CEOs from the plastic and petroleum industries, and the different politicians who are working with them. People who are against things like plastic bag bans,” Riley said.

“The whalers and ship owners back then, they were the most prominent people in society. And whether they were aware of it or not, they almost completely decimated an entire, not just species, but (several genera) of animals,” he said,

During the summer Riley made some lures out of plastic tampon applicators, went out fishing, and caught a depressingly impressive number of fluke.

I first learned about Riley a couple years ago from a video in which he attached tiny cameras to homing pigeons and released them in Havana to fly back to Stock Island. It’s a very jarring video, possibly seizure-inducing, a spastic zoetrope with lots of wind sounds and thumping wingbeats. At first you get this pigeon’s-eye view of iconic Havana – rooftops, old cars, baseball diamonds, boulevards, fountains, other pigeons. Then there’s quite a bit of ocean. Then the bird lands in the rigging of a party boat on a sunset cruise. Someone wonders aloud about the bird. Someone says it looks like the bird is carrying a tiny bomb. “Margaritaville” plays from a tinny speaker.

The bird takes off again. More water. Sand Key Light. Marinas. Stock Island rooftops. Then finally the inside of a pigeon coop, where a kind of calm takes over. You see other pigeons wearing tiny packs, fellow travelers who had just made the same flight carrying contraband cigars. There is a lot of cooing.

The project, called “Trading With The Enemy,” was a deconstruction of distance and geography, a critique and a challenge of illegality and cultural barriers, as well as an homage to Key West and its history of smuggling.

It took four years to plan the project and train the birds. Afterward there was a gallery show, whose centerpiece was the mobile coop where the pigeons had lived, built out of old slatted shutters and abandoned restaurant signs. The walls of the gallery were covered with frames full of the tiny packs used to hold the cameras and cigars, handmade out of old bra straps, with the birds’ names (Sloppy Joe Russell, Luis Buñuel, Admiral Finbar, Whitey Bulger…) stitched into them. There were also concept drawings and illustrated rosters listing which birds flew with cigars and which flew with cameras. And there were memorials as well, painted on old tin roof tiles, to the birds lost in training, or on the flight from Cuba, or to eye disease.

Looking over Riley’s other projects, one starts to pick up on themes: islands, cities, abandoned places, community events, booze, forgotten histories, trespassing, pigeons, tattoos, idiomatic visual art forms, a willingness to crack a joke, a penchant for transgressive and extralegal acts.

For his project “After the Battle of Brooklyn,” Riley built a wooden submarine, dubbed the Acorn, based on plans for the Turtle, a vessel deployed by George Washington during the Revolutionary War in an attempt to blow up British warships in New York Harbor. (It was unsuccessful.) Riley and two friends launched the Acorn and were confronted by machine gun-wielding police after coming within 200 yards of the Queen Mary 2, earning him several hours of questioning, a stint on the no-fly list, and a still-open FBI file.

“I was definitely not aiming to get caught,” said Riley. “I distinctly was trying not to get caught because I wanted to prove that I could use this technology from 1776 to basically subvert all of the technology that was laid in place during the post-9/11, Homeland Security, Patriot Act era.”

It was the tides that did him in, he said.

“The Dead Horse Inn” was a “temporary bar installation under a Queens overpass on the site of a historic shantytown that was razed in the 1930s to slake city planner Robert Moses’ endless thirst for urban development. Drinks cost a nickel and, according to the New York Times, no change was given. (His later project “Rotgut” was an illegal speakeasy in an old Brooklyn tattoo parlor.)

For “La Esquina Fría” Riley installed a synthetic ice skating rink, complete with 200 pairs of skates, near the Malecón in Havana. The rink was open to the public, and was supposed to close after a few weeks, but was used for over a year.

For “Fly By Night” he attached small LED lights to the legs of trained pigeons and released them for nightly performances from a boat docked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He revamped the project two years later for “Fly By Night (London).”

“Non-Essential Consultants, Inc.” was a recent “three-channel video installation” which Artnet News reviewed under the headline, “Artist Duke Riley Definitely Did Not Infest the Trump Hotel with Bed Bugs. No, Really, He Definitely Didn’t.”

There is great documentation of all of this, and other projects, at dukeriley.info.

At one point I asked him if he thought he could do the kind of work he did if he was a person of color.

“I suppose any time you’re doing anything in this country, that question is relevant, even if it’s not illegal. I think if I popped out of a submarine and somebody was pointing a machine gun at me and I was brown, it might’ve gone differently. Absolutely,” he said.

“I think it’s important to always push boundaries and that the boundaries of the law are often fluid. If you aren’t pushing hard one way, then you will get pushed back hard the other way. I think maybe, as a person of privilege, it’s my responsibility to think about how that boundary is constantly shifting,” he added.

On the beach, I kept finding pieces of rope and asking if they would work for whatever he wanted to do with them. He kept shaking his head no.

When I saw something that looked like, but was not, an old pregnancy test, I asked if he’d ever found one of those.

“A few,” he said. “Mostly negative.”

Finally he found a piece of rope he liked. He pulled it out of the sand and held it up for a second, before lacing it through his belt loops to hold up his shorts.

Then he went back to looking for more trash on a surprisingly clean beach.