By the end of the 17th century, the capture of men and women for colonial distribution in European markets was in full swing. The Atlantic slave trade operated from about 1525 to 1866.

During that period, roughly 12.5 million Africans were captured and shipped off the continent for New World harbors.

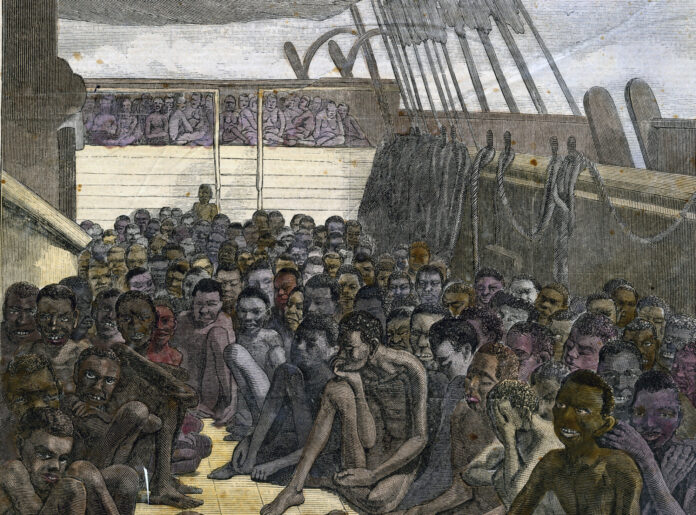

Human cargo was generally shipped in one of two ways, and the business model incorporated a mortality factor. If a “tight pack” was used, every inch mattered, and the objective was to squeeze every human being possible into the least amount of space. For the trade’s practitioners, it was a numbers game. Every square foot equaled a dollar figure, and the goal was to successfully transport as much viable product as possible for the least amount of dollars.

The other way to transport the enslaved people was a “loose pack” where fewer people were transported in the same space and, subsequently, fewer deaths theoretically occurred during the trans-Atlantic crossing because of the “improved” travel conditions. For the slavers, all that mattered was the total number of viable bodies that were ultimately delivered.

The trip across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa’s west coast is historically referred to as the Middle Passage. Of the 12.5 million people transported from Africa, nearly 2 million suffered unspeakable deaths during the Middle Passage and were tossed overboard like chum.

By 1827, the international slave trade had been illegal in Spain for seven years, the United States for 19 years, and Great Britain for 20. However, Spanish-held Cuba paid little heed to the prohibition, as evidenced in a letter written from a British officer in Havana to one in London dated July 31, 1827. It read, in part, “The illicit slave trader from this port … appears to be about to resume its former activity, no less than four Spanish vessels having during the present month sailed are the brigs Guerrero. … She is well armed, and has a crew of ninety men; and there can be little doubt that her purpose is to plunder their cargoes of slaves any weaker vessels that she may fall in within the coast of Africa.”

The Guerrero was just over 110 feet long with a beam of 27 feet, 5 inches. When the ship left the west coast of Africa to make the over 4,000-mile voyage to Havana, 561 enslaved people were held on board. On Dec. 19, 1827, Lt. Edward Holland and the 56-man crew aboard the schooner H.B.M. (His Britannic Majesty) Nimble was patrolling the Florida Straits 250 miles north of Havana. The Guerrero was spotted off the coast of Orange Cay, Bahamas. The noon entry into the Nimble’s log read, “Observed stranger to be a suspicious looking brig. I set topsail, cleared (the deck) for action and fired two guns to bring strangers to whom we observed hauling up to avoid us; made more sail.”

By 6:15 p.m., the brig was firing her cannons at the gaining Nimble, and for the next 30 minutes, the two ships exchanged cannon and musket fire until the brig feigned surrender by firing a blank and flashing a conciliatory light. The Nimble ceased fire, and the brig made another run when she did. In its attempt to outrun the Nimble, the Guerrero slammed into Carysfort Reef off of Key Largo at full sail.

According to an 1831 edition of the United States Service Magazine, “The masts of the chase were heard to fall with a tremendous crash, followed with a horrid yell from those on board, which left no doubt of her being a Guineaman.” The ship’s hull split open and when the Guerrero filled with water, 41 Africans shackled in the ship’s hold drowned where they were chained. The Niles Weekly Register reported, “The cries of 561 slaves and crew were appalling beyond description.”

The following morning, wreckers aboard the Thorn, Florida and Surprize arrived on the scene. Approximately 20 Spaniards and 142 Africans boarded Captain Austin Packer’s 39-foot schooner. Aboard Captain Charles Grover’s schooner Thorn, 246 Africans and 54 Spaniards were boarded. The two ships set sail for Key West but were hijacked by the Spanish and redirected to Santa Cruz, Cuba, where the human cargo was sold to sugar field plantation owners.

The remaining 121 Africans were boarded onto the Nimble and delivered to Key West. One person died in transit. The Africans were clothed, fed and housed for 75 days. Four additional Africans died during that period. At Key West, rumors began to circulate around the island that Spanish warships would be sailing for the island, and it was decided that for everyone’s safety, it was best to transfer the surviving 117 people to the St. Augustine area.

A letter written by the U.S. Marshal in St. Augustine to Richard Rush, Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, stated, “While they were in Key West, attempts were made to take them from the possession of my deputy, by force, and by bribery; and, the night before I removed them from the island, an attempt was made to carry off a part of them.”

Unable to support the enslaved, the U.S. Marshal rented the Africans out to St. Augustine area plantation owners. During their time in St. Augustine, 17 Africans either died or escaped. In the end, of the original 561 Africans pirated away from their homeland, 100 people were attempted to be repatriated to Africa. Nine more Africans died during the Atlantic crossing.