Sometimes you have to step back in order to move forward.

Ken Stewart, co-founder of Diving with a Purpose (DWP), takes this popular adage literally, but with an underwater twist. The organization’s special focus is to protect, document and interpret African slave trade shipwrecks and the maritime history of African Americans.

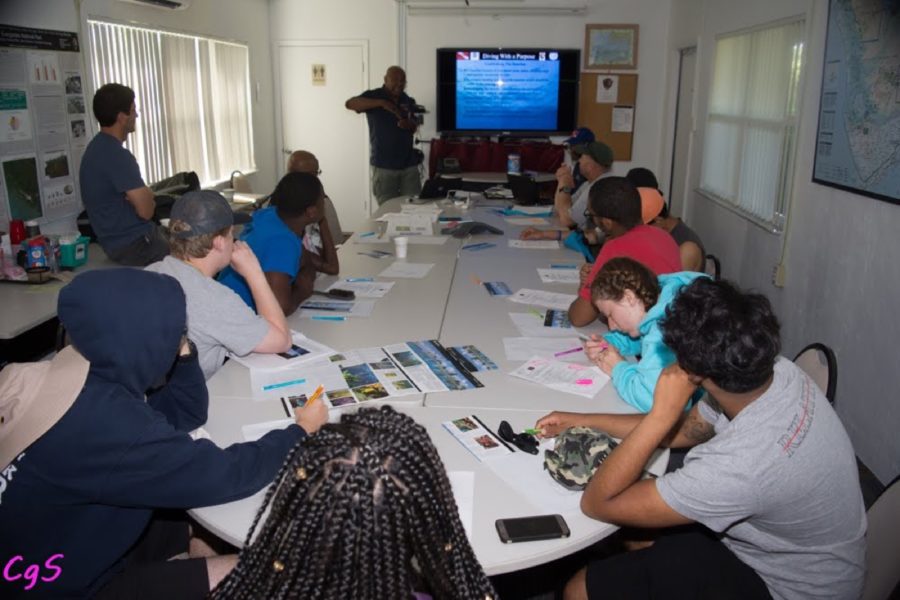

Along with its youth branch ‒ Youth Diving with a Purpose (YDWP), DWP’s mandate is to train veteran scuba divers to map and document shipwrecks to analyze history. The Florida Keys are their training ground.

DWP was founded in 2004 by Stewart and the late Brenda Lanzendorf, who was the park archeologist for Biscayne National Park. Most of the initial members were African-American, though present-day participants are very diverse. Their first mission was to train and look for the Guerrero, an infamous slave ship that wrecked in December 1827 on a reef in North Key Largo. Kidnapped by Cuban pirates and on their way to Havana to be sold, 41 of the 561 Africans on board went down with the ship, still in chains. Almost 200 years later, the wreck has yet to be positively identified.

Lanzendorf always told Stewart and their trainees that she would show them where the Guerrero was once they were ready, and they’d be the first to map her. Unfortunately, in 2009, Lanzendorf passed away.

“Brenda knew where the Guerrero was, but she took it to her grave,” Stewart said. “I don’t know if she did know or not, but, to this day, we have not found it.”

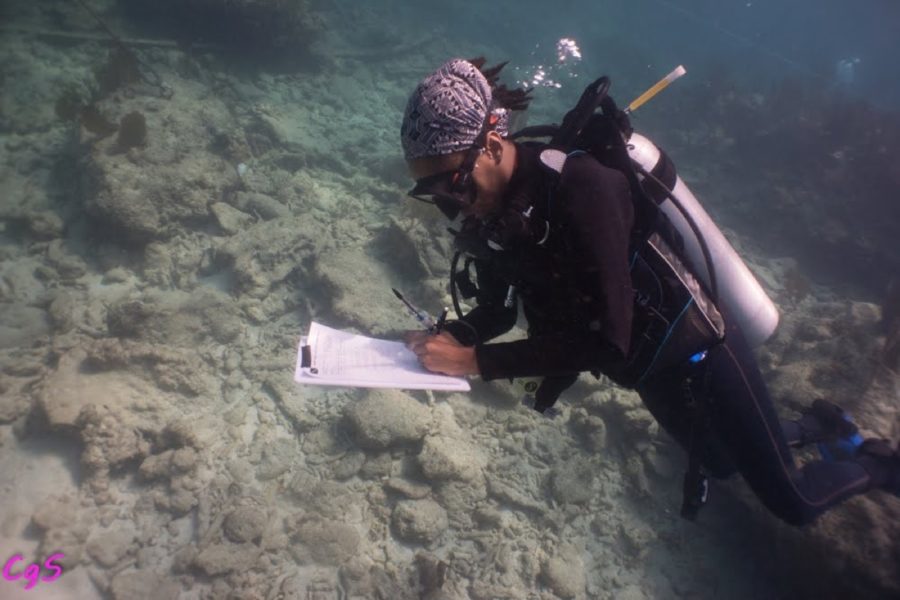

Now, that initial motivation has expanded, and DWP provides education, training, certification and field experience to adults and youths in the fields of maritime archeology and ocean conservation. Through the organization’s week-long, intensive flagship program, divers learn the history behind Keys’ shipwrecks like the Guerrero and the often-untold role that ships played in the African slave trade. Then, they deploy on an actual shipwreck in the Keys, doing historical detective work via scuba to map and document what they find.

There is a great interest in the African diaspora and documenting slave ships, Stewart said. People come from all over the world to participate in DWP’s training program, hoping to dive on a slave ship.

“There aren’t that many, unfortunately,” Stewart told the Keys Weekly. “Only six have ever been found or known, and two are in the Keys. One is the Henrietta Marie, 35 miles off of Key West, and the other, we think, is the Guerrero, wherever it is.

History can teach us, Stewart maintained. In his high school, he never learned the details about slavery or the African diaspora. When he eventually did, through the search for the Guerrero, it blew him away. He began to see the remnants of that horrible period in history in the African American community today.

“400 years of enslavement has an effect,” Stewart said. “People forget that up to the ’60s, we couldn’t even vote. Segregation was going full-steam. And that’s only 60 years ago, my lifetime. So, for people to say, ‘Get over it,’ that ain’t happening. I think this needs to be taught so that history doesn’t repeat itself.”

Stewart plays his part in this generational knowledge exchange through DWP and other youth programs he leads.

“The young people will eventually change how the world is headed,” he said. “To change the way the world is going, you gotta do it with the young people. This is my way to change the world.”

Tristan Cannon is one of those students. Currently a junior at Tennessee State University in Nashville, he has been involved with DWP for three years and now gives back as an instructor. DWP didn’t teach him more about what happened with slavery but helped him feel more connected to it.

“You can read about things through books and you understand, but it’s not the same as being able to go down and see remnants yourself. Doing that makes me feel a little closer to my history than any book or classroom could,” he said.

Experiencing the past first-hand has also allowed Cannon to draw his own conclusions about what happened, to change his perspective on history and how it affected people.

“When I see what those events actually produced, the artifacts, I understand,” he said. “And, hopefully, this little thing I can do will help in some small way to make the future better.”

Rachel Stewart, not related to Ken, is another DWP student-turned-instructor. Involved with YDWP and DWP since 2013, she notes that the dives, simultaneously cool and painful (in the historical context), help her feel closer to her ancestors.

“I never thought much about shipwrecks in our history,” Rachel said. “I’d known that the passage here (from Africa) was tough and hard, but I never thought about how ships wrecked, and about all the stories and lives that were lost. For me, the story just started when we got here.”

Since joining DWP, confronting those facts and diving on actual shipwrecks, new thoughts have entered Rachel’s internal dialogue. Now, she also thinks about what it might have felt like to be stolen from your land and packed on a ship, she says. And she considers the horror of hearing your ship was about to go under and thinking your life and story would be forgotten forever.

“That really gets me,” she said. “I think it’s really important that black people have a role in uncovering these stories because it is directly related to who we are and our identities.”

Of shipwrecks, history and identity, Rachel concludes, “You can’t see it at first, but eventually it reveals itself to you. At first glance, it might not look like much, but once you search, it will unfold in front of you as you learn what you’re looking for.”