Hanna Koch and her team at Mote’s International Center for Coral Reef Research and Restoration (IC2R3) facility on Summerland Key play coral matchmakers to help our coral reefs. They do so using reproductive interventions to assist with “coral sex.”

“We’re sexually propagating corals for research and restoration as part of the resilience-based restoration program here at Mote,” Koch explains. Sexual reproduction is crucial to the long-term persistence of coral reefs. It produces the next generation of offspring that can replenish depleted adult coral populations or disperse to establish new reefs. The process also creates genetic diversity, a critical component in adaptation to environmental stress or change. “We need corals to reproduce sexually for the survival of the species and for coral reefs as a whole,” adds Koch.

Broadcast spawning, where hermaphroditic corals simultaneously release gamete bundles of eggs and sperm into the ocean, is the first step of coral sexual reproduction. After release, gamete bundles float to the water’s surface where they break open to separate the eggs from the sperm. Gametes from different parents cross-fertilize, forming embryos, which develop into free-swimming larvae and eventually coral recruits. Recruits are larvae that successfully cement themselves back onto the reef. If they survive, these recruits become the next generation of corals in the Florida Keys.

At least that’s how it’s supposed to happen. Koch explains several reasons that this natural process, which has worked for millions of years, is failing for some species and regions. First, because of intense global and local stressors, coral populations are becoming smaller and more disconnected, she says. This lessens the chances of gametes meeting during broadcast spawning. Imagine coral singles cruising the oceans, trying to meet each other, but someone keeps moving the singles bars further and further apart.

Second, there’s spawning asynchrony, a troubling trend that seems to be increasing for some species and areas. Mass coral spawning is triggered by specific environmental cues involving moon phases, water temperatures, wave action and several other natural signals. This is how an entire reef can spawn or “go off” within minutes, leading to the greatest chance for fertilization success. Because gametes remain viable for only a few hours after release, synchronized timing is incredibly important. Therefore, Koch explains, “When environmental cues that corals rely on for synchronized mass spawning break down, you get asynchronous spawning and missed opportunities for fertilization.”

Finally, local environmental conditions linked to chemical pollutants and acute stressors can lead to failed sexual reproduction and recruitment, meaning corals cannot initiate sexual development and produce gametes or if they do, the resulting larvae have a hard time sticking back onto the reef to grow into adult corals.

Basically, the signals that have been telling all coral gamete singles to meet at the same singles bar at the same time for millions of years are failing, so they’re showing up at different times to different singles bars, or not at all. And should any happy coral couple successfully fertilize and develop into larvae, even those larvae are having a hard time making it back onto the reef.

Enter science. “Asynchrony is one of the biggest issues,” Koch says. “Without synchrony, every other step in the sexual cycle will fail.”

Koch explains what her team is doing to combat this. In-situ spawning nurseries like the ones at Mote provide optimal growth conditions so corals reach sexual maturity more quickly. For most corals, sexual maturity is size-, not age-, dependent; so, the faster they grow, the sooner they’ll be ready to reproduce. Then, they can be brought into the lab for more controlled and successful breeding. On land, scientists do not battle with unpredictable weather, predators of coral gametes, and unfavorable ocean conditions, so gametes can be more easily collected and fertilized. This is exactly what Koch and her team did this year.

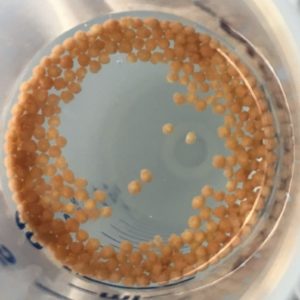

During this year’s August spawning event, they brought 62 colonies of staghorn corals into their tanks. Nine of the 62 colonies released gamete bundles, ranging from a few to hundreds. Five of the nine spawned colonies released gamete bundles on multiple nights, with the two most prolific colonies spawning on different nights (asynchrony). Even so, Koch was able to produce 400 larvae from two genetic crosses. Ultimately, she ended up with 200 genetically distinct “coral babies,” or sexual recruits.

These babies are now happily growing in tanks at Mote. They will eventually be used to add fresh genetics to Mote’s Coral Reef Restoration Program for outplanting back onto local reefs. “This is a huge step for us, as this is our first home-grown batch of corals produced entirely from Mote’s own restoration broodstock, from start to finish,” says Koch. “Now, here at IC2R3, we can accomplish all aspects of both sexual and asexual reproduction in-house.”

The IC2R3 facility offers free public tours where visitors get behind-the-scene glimpses of Mote’s restoration activities in action.