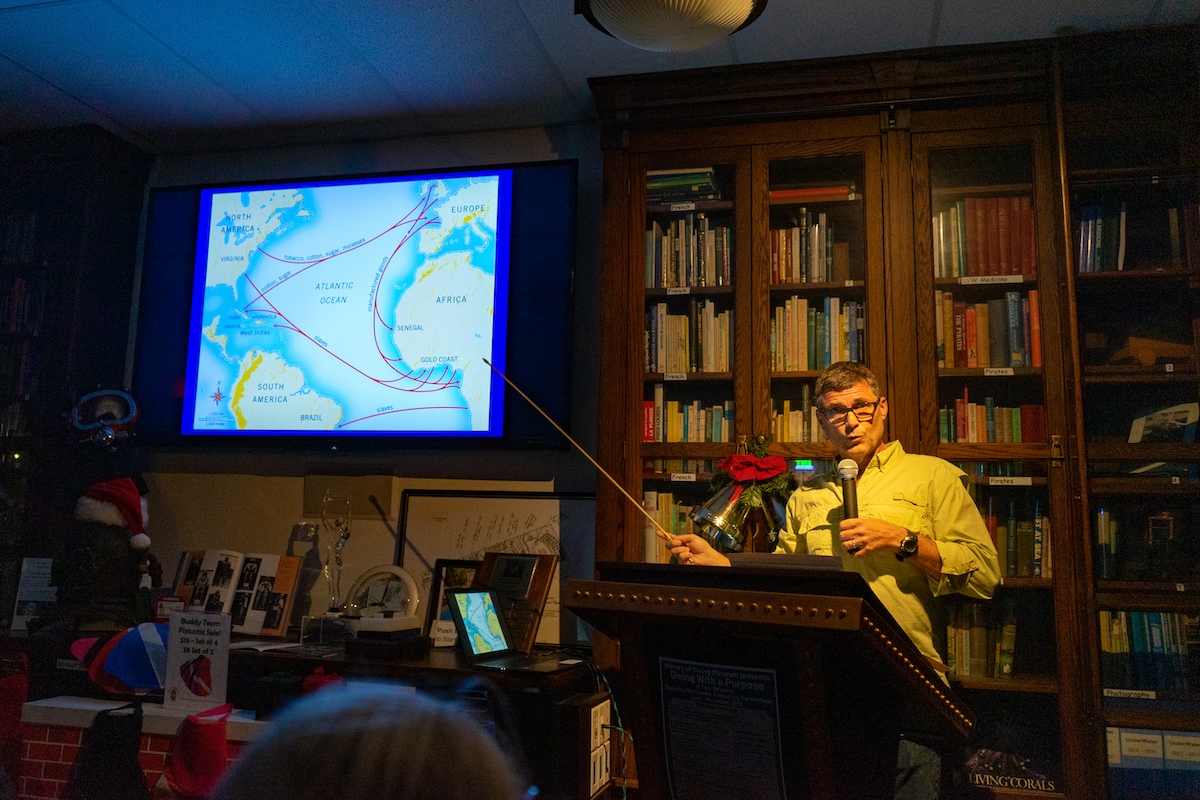

Corey Malcom, director of archeology at the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum in Key West, spoke to a packed house at the History of Diving Museum’s December “Immerse Yourself” lecture series.

Malcom, a recognized expert in shipwrecks, archeology and the Keys, offered an archeological analysis of two shipwrecks and a gravesite found in the Keys to explore the role the island chain played in the transatlantic slave trade.

“The slave trade is a viable subject to research and explore,” Malcom said to start his lecture. “And the archaeology of the slave trade is important because it gives tangible and unbiased evidence of what happened.”

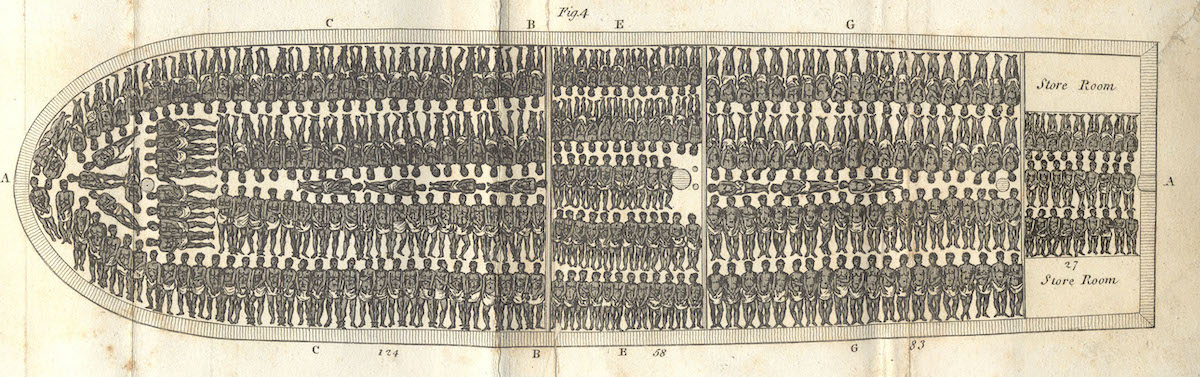

The transatlantic slave trade operated for over 350 years, transporting 12 million captive Africans across the seas. It didn’t happen the same in 1510 as it did in 1860, Malcom said, adding that the trade changed due to economic, political and legal pressures.

The first ship discussed was the Henrietta Marie. In 1972, Mel Fisher’s Treasure Salvors team discovered the wreck on the north side of the Keys, but moved on because it wasn’t the Atocha wreck they were seeking. Eventually, another archeological crew found the ship’s bell, which read “Henrietta Marie 1699.” With more research, the Henrietta Marie became the first slave ship ever to be found, excavated and presented to the world.

The ship was involved in the triangular trade route, bringing European fine goods to Africa to trade for people, who were brought back across the Atlantic and sold in the Caribbean for cotton, sugar, tobacco, and molasses. Those were brought back to Europe.

The Henrietta Marie was only in her second journey as a slaver when she sank on New Ground Reef in the Florida Keys in 1700. Archeologists pieced together her history from the artifacts uncovered. Iron bars and pewter goods found on the ship were used to buy slaves. “In fall 1699, it would take 12 to 17 iron bars to buy a person,” Malcom said. “It’s a pretty shocking thing to learn that’s what a person was worth to some.”

“They were trading for people who didn’t want to be on the ship,” he said, describing 82 sets of shackles found onboard to lock captives together.

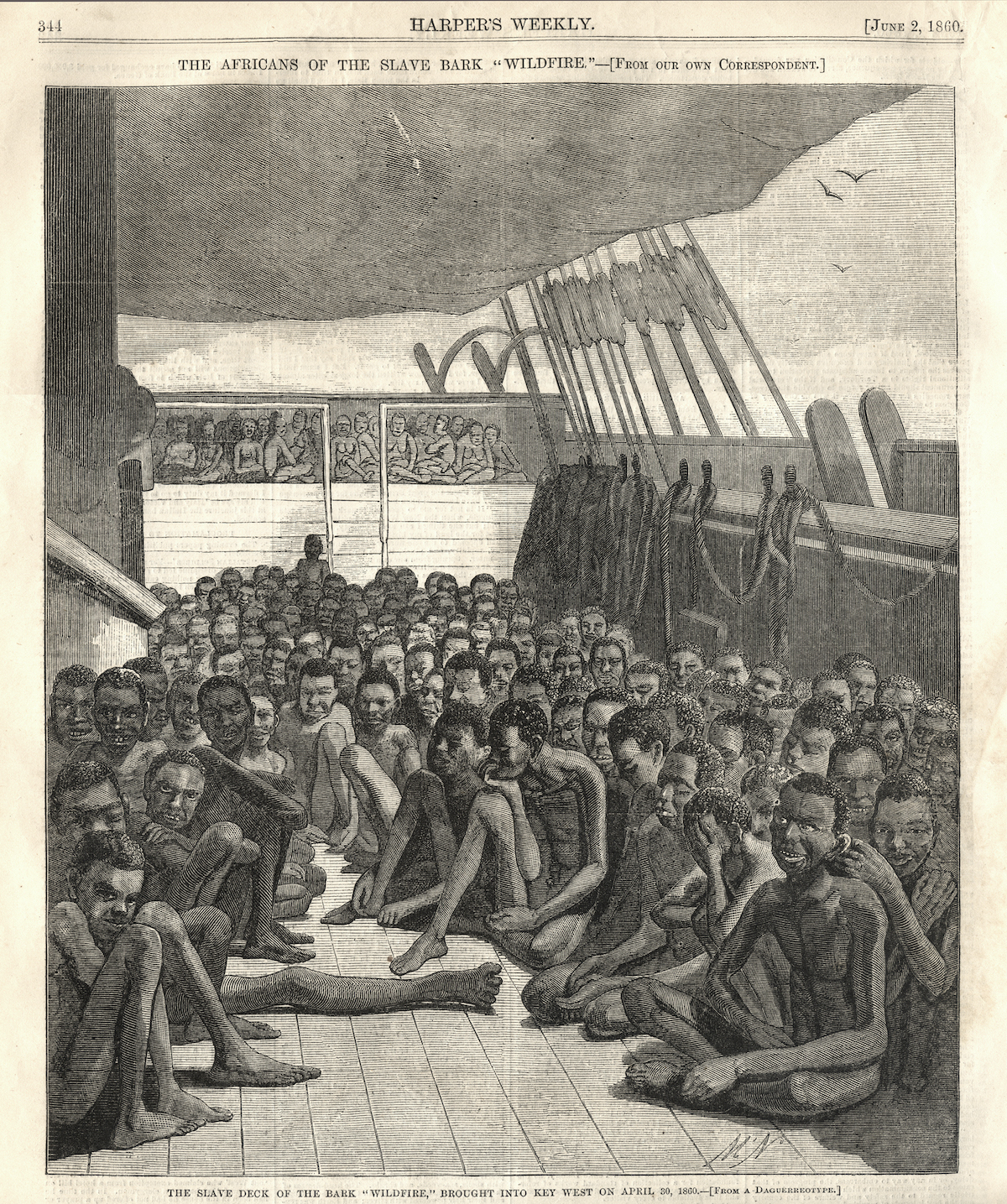

More than 120 years later, slavery was going out of fashion and the trade was even outlawed in many places. That didn’t stop pirates like Jose Gomez from capturing and selling people, so the British navy patrolled the Atlantic to stop illegal slave ships.

The Guerrero was one of those illegal ships and Malcom’s second tale of the night. Built in 1813 in Connecticut, it ended up a Cuban pirate slave ship under Gomez’s control. In 1827, his luck ran out. The British navy ship H.M.S. Nimble spotted the Guerrero and engaged in a gun battle in the straits between the Bahamas and Florida.

The Guerrero wrecked in North Key Largo, and the Nimble struck five minutes later. “There’s a rich historical record for the Guerrero,” explains Malcom. “It’s not a question of what happened, but where.” Archeologists searched for the wreck for years off the bearings the captain of the Nimble had scribbled in the ship’s log.

In 2004, Malcom and his crew used a magnetometer, a device towed behind ships to locate iron underwater, and found a shipwreck debris field spread across a shallow reef in the Upper Keys. Clues such as ballast stones pointed to the Guerrero. “Every rock in this area is coral rock or limestone,” describes Malcom. “So if it’s not that, it came from somewhere else.” Other finds, like white oak wood from the Northern Hemisphere, glass fragments and scalloped plates helped Malcom’s team zero in on a time period – late 1700s, early 1800s.

They can’t definitively identify the wreck as the Guerrero because so little remains and because the fragments are spread across one of the most pristine reefs in the Keys. “Nature trumps history,” smiled Malcom. “No digging on a beautiful reef with so many endangered species.”

To end, Malcom tells the story behind the African Cemetery in Key West. At the end of the transatlantic slave trade, the U.S. Navy intercepted two American slave ships illegally selling slaves to Cuba. The ships were seized and towed to Key West, the nearest port, and 1,432 African refugees flooded the Southernmost City.

They were housed in barracks, and 40% of them were ultimately sent to Liberia in West Africa. The rest fell victim to the system, dying somehow in the process. Many were buried in Key West, but the location was a mystery — until 2002.

That’s when a ground-penetrating radar survey discovered the first graves in Higgs Beach Park, under the West Martello Tower. This site is the only cemetery in the U.S. composed of people caught up in the slave trade who were intended to be liberated. “It’s touching, unique, and we always need to remember these people buried in Higgs Beach Park,” added Malcom.

He closed by saying, “Finding a site or objects relating to the transatlantic slave trade is always bittersweet: These are the things that hold the information archaeologists seek, but they are also tied to terribly tragic and cruel events.”

For more stories, visit melfisher.org and floridaslavetradecenter.org.