Two seasoned watermen share their stories

Lobster sport season (July 29-20) always presents its own set of challenges. In the frenzy to be first to the “tails,” many accidents do — and will — happen as an estimated 30,000 visitors converge on the islands already full of locals who want some too. Most aren’t so serious. It won’t kill us to wait a few extra minutes in the check out line at the grocery store or contend with more cars on the road, but mishaps on the water are much more serious.

Kristen Livengood, a Weekly staffer, and her brother Chase Grimes, are experienced watermen. They grew up in the Keys diving, free diving, fishing and generally cavorting on the water. More than anyone, they love a good sport season. More than most, they know what they are doing.

But even experienced divers run into problems on the water. And as the annual madness approaches, they were both willing to sit down and talk about two of the real dangers of diving and free diving — two out of three methods for bringing up the briny beasts.

BLOWN EAR DRUM

How it happens:

Dr. John O’Connor of Marathon says he doesn’t see it very often, but it does happen when a scuba or free diver fails to equalize pressure between the inner ear and the environment outside. Kristen said she feels pressure in her ears every time she dives, usually solved by backtracking towards the surface for a few feet. This time, she was 80 feet down on a night dive on the opening day of grouper season. Instead of descending feet first, like she normally does, she was diving down head first.

What it feels like:

Although ear trauma can be excruciating, Kristen said she only felt a “pop” and then “cold water rushed into my head.” She said she felt dizzy, nauseous and out of balance. When she surfaced, the water pouring out of her ear felt like warm blood, but there was no sign of it. Dr. O’Connor said when an ear drum bursts as a diver descends, water rushes in. When a diver is surfacing, the air inside an ear bursts the drum outwards.

What you should do:

Stop diving. Get back to shore and consult a doctor. He or she may prescribe decongestants or antibiotics and probably lay down a “no flying” and “no diving” edict. Kristen waited the prescribed six weeks, plus two more, before diving again just recently. (See the story on page xx.) “All was good, and I learned never to push the pressure again. I would have been so mad if I missed mini season.”

Related issues: A blown ear drum is a pretty extreme case of an ear-related dive injury. Dr. O’Connor said he also treats barotrauma (similar to a blown ear, but where the ear drum only stretches to a painful limit) and swimmer’s ear (an infection of the external ear canal). The latter can be treated at home with a blow dryer (!) or a mixture of rubbing alcohol and vinegar. The vinegar restores the normal pH.

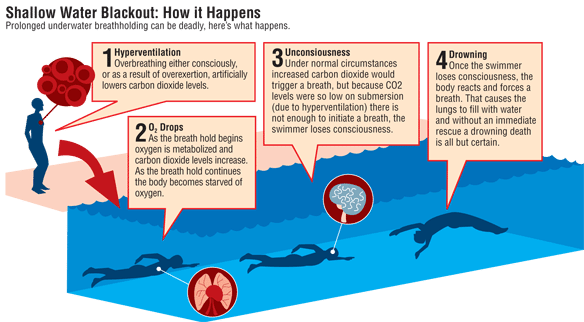

SHALLOW WATER BLACKOUT

How it happens:

Shallow water blackout is when a free diver losses consciousness near the end of a breath-hold dive. Divers who have experienced this condition, and lived to tell about it, said they did not experience an urgent need to breathe. Experts surmise that while a build up of carbon dioxide in the lungs causes a voluntary need to gulp air, low levels of oxygen do not. If the cerebral hypoxia tips, the diver loses consciousness. The body’s involuntary reaction is to begin breathing again. If the diver is face down on the surface, or underwater, the result is drowning.

What it feels like:

Chase Grimes was free diving near the Dry Tortugas in 130 feet of water. He was after a grouper and said he stayed down too long. “I could still think, but my body wasn’t responding. My body wouldn’t function.” Grimes said that although he knew the situation was serious, he wasn’t panicking on a biological level. Others who have experienced shallow water blackout cannot remember the event. Grimes said he surfaced and took a big breath of … saltwater wave. He dry heaved and that sound signaled his dive partner that something was wrong. Brandon Bertini looked and saw Chase floating about 15 feet underwater. He pulled him to the surface and blew on Chase’s face to stimulate the breath reflex.

What you should do:

ALWAYS dive with a reliable buddy. KNOW your limits and err on the side of CAUTION. And don’t hyperventilate before free diving. According to the Shallow Blackout Water Prevention organization, hyperventilating before a breath hold dive is dangerous because low oxygen levels occur before the levels of carbon dioxide get high enough to trigger the urge to breathe. Repetitive breath-holding can also give rise to the same condition.

If you suspect someone is experiencing shallow water black out, get them to the surface. Take off their mask and start CPR. Get professional help immediately.

Related issues:

The “bends” — or decompression sickness — is also another potentially fatal diving accident most commonly associated with tank divers. The best way to understand this is to think of a bottle of soda, the gas is invisible when it’s dissolved in the solution. But when the bottle opens, the gas leaves the solution in the form of bubbles. As a diver surfaces, the nitrogen which has dissolved into his or her tissues bubbles out and can block blood flow and a host of other nasty conditions.