“To Succeed, You Must Descend.”

This was the motto of the NEPTUNE Project when it successfully completed experiments in extreme work and living last October.

NEPTUNE is an acronym for Nautical Experiments in Physiology, Technology & Underwater Exploration. The Explorers Club-flagged expedition brought five researchers and explorers from the U.S. and Canada to Key Largo to complete groundbreaking research on working and living in extreme environments.

“My overriding goal in life is to make aquanauts and astronauts safer, so I do research to that effect,” said mission commander and principal investigator Joe Dituri. “I’m a retired navy special ops diver. I lost a guy to hypercapnia (build-up of carbon dioxide), and I said, ‘We’re smarter than this, we can fix this.’ So, everything I do is to make extreme explorers safer.”

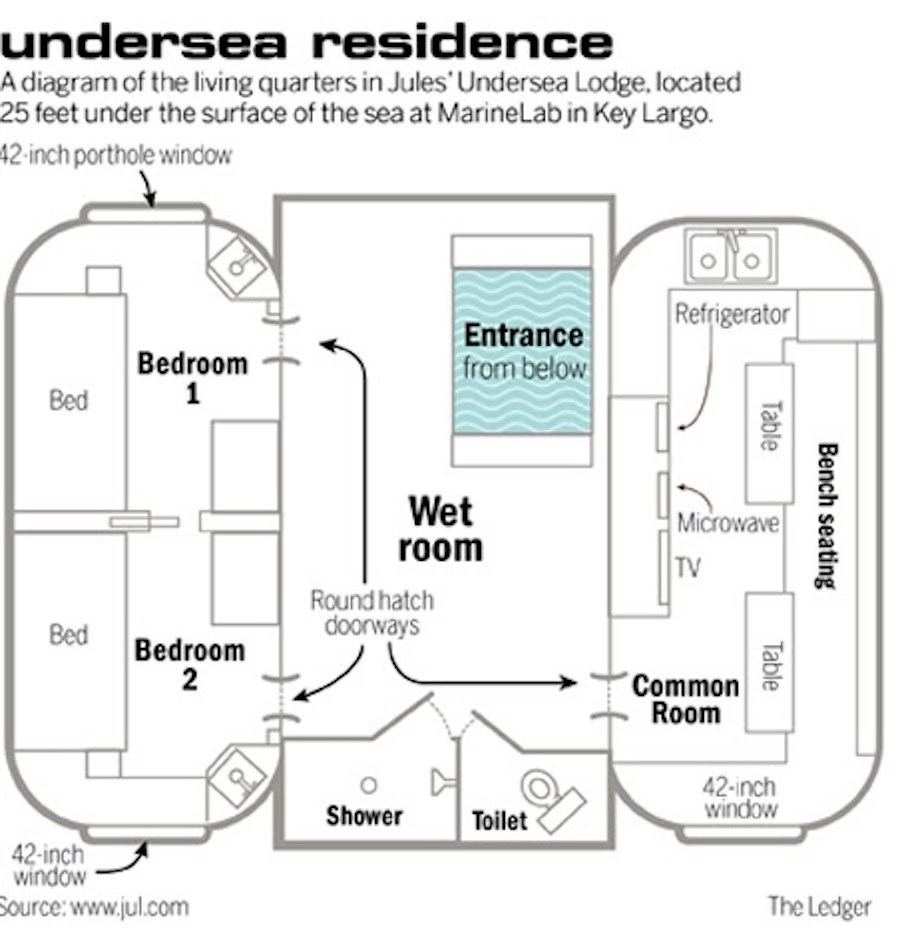

Jules Undersea Lodge (JUL) is an underwater hotel that sits completely submerged in 25 to 27 feet of water in a Key Largo lagoon. The former underwater research laboratory is fully stocked with a kitchen, radio communication to the surface, and wifi. The habitat is considered an isolated and confined environment, or ICE. The term is often used by astronauts and arctic researchers who spend long periods of time living and working in tight quarters cut off from a harsh outside environment.

Because researchers can only enter using scuba and can dive in the surrounding lagoon freely without surfacing, JUL became a great stepping point for Project NEPTUNE. The crew spent six days and five nights completely submerged, performing cutting-edge science experiments and technology demos with implications for diving and space exploration.

“We investigated the physiological and psychological effects of living in a saturated environment for six days,” said mission executive officer Paul Bakken. “It was great. It actually surprised me a little. I didn’t think I’d sleep as well as I did, but I slept just fine. I think I even gained weight.”

Bakken spoke to the Weekly while mission specialist Doug Campbell unplugged from an “evoked response” test that measured cognitive speed and function.

“We’re doing groundbreaking research in diving — underwater EEG, EKG, cortisol testing, sleep diaries, sleep studies and stress diaries,” said Dituri. “This is really cool science stuff. This is the first time your brain waves have been checked underwater. Nobody has ever done that before, not even the U.S. Navy. Frankly, the technology didn’t exist to do it before this.”

Dituri said the tests measure psycho-social resilience, sleep and stress reactions to ICE stimuli and conditions.

Shawna Pandya, the physician and crew medical/safety doctor, pointed out her ISANSYS Lifetouch vital sign sensor, a portable, lightweight patch that monitors heart rate and respiration rate that all crew wore throughout the mission. It documented their bodies’ reactions to prolonged saturation, multiple daily dives and social isolation. The crew additionally tested ways to retrofit the sensor to work with wetsuit dives, using plastic wrap and silicone grease.

Dituri described several other technology demonstrations that the mission undertook.

Pandya used virtual reality to consult with a remote radiologist in Canada to diagnose and repair a simulated shoulder fracture. The virtual medical suite allows for decision-making support for long-duration missions and remote/resource-limited environments, Dituri said.

“This was just like if Dr. Pandya was in a spaceship far away and couldn’t come out for treatment. This is tele-medicine,” he said. “When you can be in a VR space, she can point a wand in space and ask how she should reset this fracture, how she should splint it. Then, the remote doctor can give instant feedback.”

Partnering with a Japanese anesthesiologist-researcher, the team also tested 3D-printed inhalation/ventilation devices for remote emergencies.

Bakken noted that the goal of the mission was to learn how to live and work better in an undersea or another analog environment. He agreed that the undersea habitat at JUL was a “very good analog” for a space environment like the International Space Station (ISS) and that the technology demonstrations would support the eventual deployment of similar equipment to the ISS.

“It felt better than I thought it would,” said Campbell. “I wasn’t claustrophobic at all, but I felt like I had a cold the entire time because of the extra pressure.”

The mission specialist also pointed out the applications for space travel, saying, “As people go towards the moon and maybe Mars one day, the more we can learn on earth about what happens to the body in these long saturation situations, the better and safer.”

The mission completed, the team is eagerly sorting through data while setting sights on the next, longer endeavor: Dituri wants to spend 100 days in an ICE to test the limits of the human body and new technology.

Laughing, Bakken noted, “This isn’t my profession, by the way; I’m an attorney. That’s what I do to pay the bills, but this is what I love. I’ve always been interested in space and space exploration, and now, we’re making it safer.”