Before diving into this 20th-century mosquito story, I need to backtrack. In last week’s 19th-century mosquito story, I referred to yellow fever and malaria as the same. As one of my readers thankfully pointed out, I was wrong.

According to the Cleveland Clinic: “Yellow fever is not the same disease as malaria, but they have some things in common: They are both spread by mosquitoes. They both cause fever and other flu-like symptoms. They both can cause jaundice, severe sickness and even death. There are also significant differences between malaria and yellow fever, such as: Malaria is caused by a parasite, while yellow fever is caused by a virus. The types of mosquitoes that spread malaria are different from the mosquitoes that spread yellow fever. There is a vaccine to prevent yellow fever but no vaccine to prevent malaria.”

In any case, mosquitoes have been a part of living in the Florida Keys since warm-blooded animals have inhabited the island chain. Early pioneers built their homes facing the Atlantic to reap the benefit of the ocean breezes that acted as both a cooling agent and a primitive means of pest control. Fires were burned because the smoke was a pest deterrent. Smudge pots produced thick clouds of dark smoke, which also helped keep the bugs away.

One natural deterrent to the mosquito population is a small, minnow-looking fish with a big belly called, appropriately enough, a mosquitofish. The local variety is Gambrusia rhizphorae, the mangrove mosquitofish.

Mosquitoes can only reproduce where there is access to fresh water. Eggs are often laid after the female dines on a little warm blood. The eggs, referred to as rafts, are either laid in water or areas prone to collecting water after rain. Eggs can stay dormant for months and as long as a year, waiting for the next rain to create an adequate pool for them to hatch.

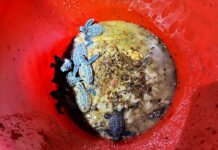

When they do, and the larval form of the mosquito emerges, they are commonly referred to as wrigglers – the larvae spend their infancy wriggling their wormy bodies through the water. Because mosquitoes are attracted to fresh water, one technique used for pest control is to engage the mosquitofish as a biological operative.

Mosquitofish are stocked in ponds and rain barrels near a home. When the pests deposit their eggs in the convenient source, the rafts hatch and the wrigglers emerge, to the delight of the mosquitofish. One adult mosquitofish can consume up to 100 wrigglers in a single day. These same practices are employed today.

In the 1920s, an anti-mosquito movement was swelling in the Sunshine State. Announced in the April 9, 1926 edition of the Key West Citizen was a meeting of the Florida Anti-Mosquito Association scheduled for May 5 and 6 in St. Augustine that “should be attended by people from every section of the state, for at this conference it is proposed to launch a highly important movement that will be state-wide in its scope.”

The article added, “The aim of this association is the ultimate and complete annihilation of the mosquito from this great state of ours.”

They were lofty goals.

In 1936, one of the WPA programs in Key West was eradicating mosquitoes from the southernmost city. A June 25, 1936, story in the Key West Citizen described the efforts of “spraying crews” going around the island. At that stage of the game, one note stipulated that it was up to individuals and the community as a whole to eliminate those places where rainwater pooled and the little vampires bred — tin cups, old tires and the like.

After all, as stated in the article, “A community continually at the mercy of those pests is considered more or less undesirable from the standpoint of comfort. It is unpopular and leads to depreciated property values.”

By 1938, mosquito killing was a little more organized. James H. LeVan, the future head of the United States Public Health Service, traveled to Key West in December to meet with a team of five members of an anti-mosquito unit. In addition to combating the pests by spraying chemicals, the crew removed those little breeding pools created in tin cans and other impromptu reservoirs. The crew poked and sprayed around the island until April, when they returned to their home base in Miami.

Heavy rains made headlines in the Feb. 24, 1939, edition of the Key West Citizen. “The recent rains in Key West are the cause of the appearance of millions of mosquito larvae (wiggletails) in the pools of water remaining.” The headline was subtitled, “Public Health Force Turns To Marsh Skeeters.”

The fear in Key West was that while workers were in Key West oiling pools, spraying, and dumping over those little containers serving as little mosquito incubators, those same measures were not being taken on the other islands. The risk was real, as some species of mosquitoes can fly as far as 40 miles for the chance to sip a little warm blood.

By 1940, advertisements for an anti-mosquito campaign began appearing in the local newspapers, and in 1949, a special act of the Florida Legislature created the Monroe County Anti-Mosquito District. Today, the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District employs various techniques for mosquito eradication, including the aerial delivery of pesticides and the deployment of the trucks that sometimes buzz down neighborhood streets, leaving clouds to dissipate behind them.

It has been raining recently, and, as a matter of note, I laughed as I wrote that last sentence because, as I did, one of those mosquito-spraying trucks went chugging past the Sioux Street office window.