PART 1

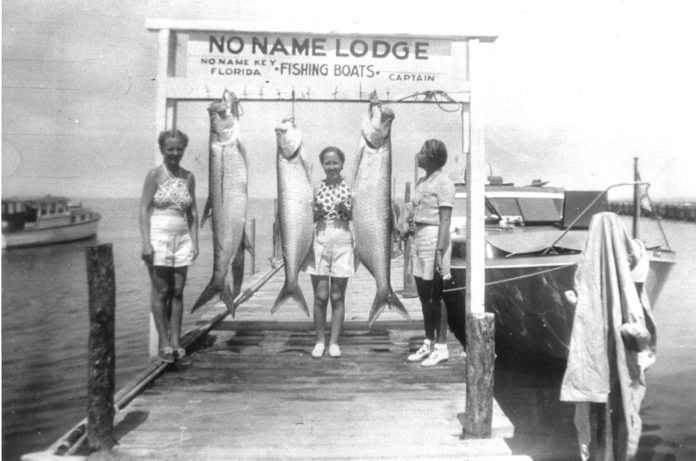

No name has been given to many of the 1,700 islands considered part of the Florida Keys archipelago, but No Name Key has been assigned to individual islands twice.

One of those islands is usually overlooked by all but those living around MM 11, where the island is visible from the Overseas Highway, on the gulf side of the bridge connecting Rockland Key and Boca Chica.

Most people barely notice the small island covered in mangroves because it looks like scores of other islands dotting the shallow waters seen from the asphalt and concrete of the Overseas Highway. This island’s modern name is Anomino Key. Anomino is the Spanish word for anonymous, so its name seems particularly fitting. In 1878, however, the U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey Chart #169 identified it as No Name Key.

There is another island named No Name Key with a significantly larger story to tell, which is why the month of August will be spent hitting all of the island’s historical highlights.

This No Name Key has been linked to Big Pine Key since pioneer stories have been told and physically connected to the island since the construction of State Road 4A, the original Overseas Highway, circa 1928.

To reach the island from the Overseas Highway, from Big Pine Key, the second largest of all the Florida Keys, turn on to Key Deer Boulevard and then turn again at Watson Boulevard, the path of the original highway. The road will take you to what is perhaps the island’s most established establishment, the No Name Pub (it will be a few weeks before we get to that story).

In 1772, cartographer John William Gerard de Brahm identified it as Edwards Island. The name proved an isolated incident. According to F.H. Gerdes’ 1849 pamphlet, Reconnaissance of the Florida Reef and all the Keys, “The Island N. by W. from Summerlands Keys, lying between them and Little Pine Island is called No Name Key.” It has been No Name Key ever since.

According to the 1870 U.S. Census, the island had a robust population of 45 people, living in at least 16 houses. By comparison, Big Pine Key had a single man named George Wilson from New York living on it. Wilson was identified as a charcoal burner; he made charcoal, a legitimate way to make money in the pioneer days. On No Name Key, the men living on the island were all identified as either farmers or seamen. With the exception of one individual, all of those families calling the island home were Bahamians.

The exception was Nicholas Matcovich, who, at the time of the 1870 census, was identified as a 45-year-old man with a Bahamian wife named Eliza and a 1-year-old son named George. Nicholas was not Bahamian but of European descent, and his fascinating story is mostly as murky as the Louisiana Delta. Still, there are enough details from his time on No Name Key to tell a one-of-a-kind pioneer story.

In at least one document, he has been described as the King of No Name Key, and whether or not the claim bears any truth, Matcovich’s story is legendary. Who was he? That depends on who is telling the story – at least his origin story does. Nicholas Matcovich is generally referred to as a Russian immigrant born in Austria sometime between 1827 and 1832 but also maybe in 1825. According to the 1870 census, he was 45, a number that would have put his date of birth closer to 1825.

According to an article written by R.F. McClure for the Nov. 26, 1904, edition of Atlanta’s The Sunny South, he was born in America. As the story is presented, McClure visited No Name Key, Matcovich’s property, and interviewed the man, which, by all accounts, was not an easy thing to do. If his story is to be believed, it contradicts some aspects of the stories commonly told about him, and provided amazing details about his life at No Name Key.

The usual story suggests Nicholas was born to Russian parents in Austria and that his father was a man named Johan. In this 1904 account, Nicholas referred to his father as Eli. Also, according to what is represented as a firsthand account, Nicholas was born in America after his parents came to the country to buy farmland. It was after he was born, but while he was still a small boy, that his father returned to Dalmatia, recognized today as a region of Croatia, and did so, apparently, without his mother.

It was while back in Dalmatia, after Eli married a rich wife who wanted Nicholas to work in the fields, that Nicholas chose instead to sail away from his father and the fields aboard a merchant vessel where he lived a seafaring life for several years – though, according to the story, “never German vessels.”

It is generally agreed that Nicholas came to (or returned to) America circa 1848 at New Orleans and became a U.S. citizen in 1856. During the Civil War, he worked on blockade runners for the Confederacy, operating between Charleston and Havana. After the war, he moved to Jacksonville, where he met his wife, Eliza Ann Carey. From Jacksonville, they left for Key West to be closer to her Bahamian friends and family.

And that is where we will stop until next week when we dig deeper down into the dirt of the No Name Key story.