When State Road 4A opened to traffic in 1927, it was the only automobile route bridging the mainland to Key Largo. On the mainland, the road traveled away from Florida City and between Little Card Sound and Barnes Sound to the bridge. Most of it was part of Dade County. The last half-mile or so of the road before it rolled over the bridge belonged to Monroe County.

For decades, there were only two reasons to make the drive. Either you were going to Key Largo or one of the other Keys, or you were headed about 10 miles down the road to fish, eat or drink a beer at one of the fish camps that popped up along the highway right-of-way. They came and went. Among the list were the White Elephant Fishing Camp, the Davis Fishing Camp, and some more familiar names like Fred’s Place, Smitty’s and Alabama Jack’s.

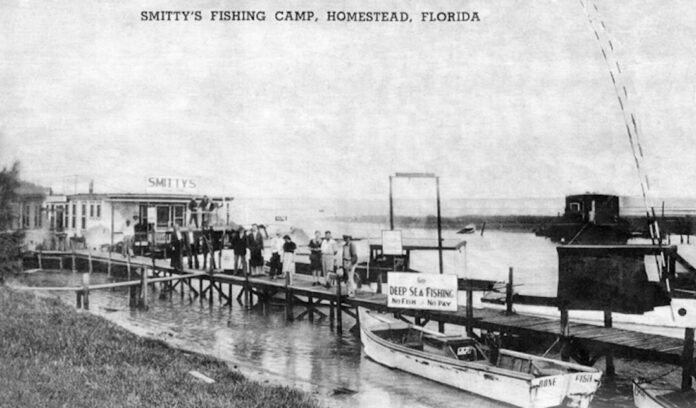

Earl Smith was one of the first to set up camp. In the 1930s, when the Barnes and Card Sounds were still filled with shrimp, he caught them by the bucket and sold them to fishermen. Business was good and Smith expanded his business, selling bait, renting boats and chartering fishing trips. As early as 1936, the fish camp was mentioned in the local newspapers. In the Miami News, dated March 31, 1936: “We arrived at Captain Smitty’s Place for an overnight fishing trip.”

Fred Wignall set up a fishing camp called Fred’s Place, offering bait, boats and beer.

When 1965’s Hurricane Betsy devastated the small community, the storm blew Fred’s Place from one side of the road to the other. When he rebuilt, hatches were built into the walls so water could just flow through. Also, the floor had a decided slant, which is why Fred’s Place became known as the Tiltin’ Hilton.

People used to call the area where Fred’s Place and Smitty’s Place used to be, and where Alabama Jack’s still stands, Downtown Card Sound. The community patched together along the stretch was a rag-tag collection of trailers, houseboats and slapped-together homes built over the water. You lived how you lived and did what you had to do to make a buck, fishing, selling blue crabs, or whatever.

In its heyday, more than 100 people called it home. It was an excellent place to escape the real world. There was nothing official about Downtown Card Sound, no running water, trash pick-up, or a telephone. Because of the isolated nature of the Card Sound community, and because it stood with feet in both Dade and Monroe Counties, the police did not regularly patrol the area.

Somewhere around 1973, Fred sold his place to the McQuaid family. In a Miami Herald story published on March 3, 1974, Susan McQuaid, who, with her husband and father, owned Fred’s Place, said: “The sheriff’s deputies told us they’d come if we called them, but they said it’d take a while to get here, so if there was any trouble, we’d better handle it ourselves.”

While only a few experiences are more reliable than death and taxes, change is certainly one. The shrimp, blue crab and fishing isn’t what it used to be. Neither is Downtown Card Sound and for a myriad of reasons. Things were brought in, but things were not necessarily brought out. Left to its own devices, it became something of a junkyard and a bit of an environmental disaster.

While a hearty few lived there for decades, people had always drifted in and out of the community. Twice, the Dade County side came in to crack down on the illegal structures. Lawyers intervened and agreements were made. Some people packed up and abandoned their homes, and some sold their businesses. In some instances, it was because the owners were just getting old and needed to retire, while others no longer wanted to deal with headaches associated with the local government butting their heads in places where the Downtown Card Sound community felt they had no business.

These days, beyond Alabama Jack’s, there isn’t much left of the old Downtown Card Sound. “Alabama” Jack Stratham sold his fish camp circa 1973, 20 years after he first created it as an escape for his friends and family. It closed for a while, but not for long. A Miami Herald article dated May 11, 1976, states that Howard Jacobs had owned Alabama Jack’s for about two years. Also, it was Jacobs who paid $4,200 to have the first phone line brought out to the isolated community. It was connected to Alabama Jack’s and a Homestead exchange phone installed at the bar.

The Alabama Jack’s we stop at or drive by today is, at the very least, the third version of the establishment. The first was created in 1953. When Hurricane Betsy mauled it in 1965, a barge was brought in, and Alabama Jack’s was built on top of it. It was around 1977 when the barge on which Jack had built his business began to fall into the water and was replaced by the building that stands where it is now.

The business has been bought and sold time and time again. In a story published in the Miami News on Feb. 25, 1980, Rose Presti explained why she bought the business: “I came here and just loved the scenery. I found the man who had rebuilt Alabama Jack’s, and I bought it. I paid dearly for it. I can’t discuss the deal, but I am sure there will be no questions regarding the title.”

It has changed hands a time or two since, but a few things have remained the same.

Alabama Jack’s is still one of South Florida’s classic dive bars. Also, they still serve what I think (and many others do, too) are the best conch fritters. While most cooks lean into the spice when frying their conch fritters, Alabama Jack’s leans into the sweet. They are a little bit different than almost every other conch fritter in Monroe County and the Keys, and with (or without) some cocktail sauce and a cold beer, they are worth the extra time it takes to drive the alternate route to the Keys and drive down Card Sound Road.