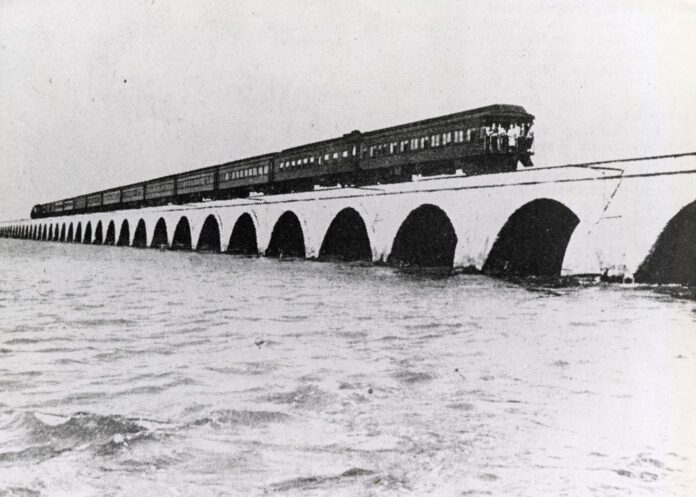

The Bahia Honda railroad bridge is one of the iconic sights in the Florida Keys.

Because of its truss design, and the way it was elevated over the water, it stands out like no other bridge in the Keys.

Two bridges of a similar truss design were incorporated into the Over-Sea Railroad, the Bahia Honda Bridge and the swing portion of the Moser Channel Bridge on the old Seven Mile Bridge that could be swung open to allow boats to pass.

However, it should be noted that the Long Key Viaduct deserves special mention.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a viaduct as “a long elevated roadway usually consisting of a series of short spans supported on arches, piers or columns.” A viaduct design was used to build 26 railroad bridges between Lower Matecumbe Key and Key West. Out of all the bridges connecting Miami to Key West, it is the likeness of the Long Key Viaduct represented on Florida East Coast Railway logos and that of the Monroe County Library System.

A viaduct offered a more stable design than those bridges built of wooden trestles like the ones created to cross the shorter expanses between islands in the Upper Keys. One of the things that using a viaduct or trestle bridge did was allow for the free passage of water below the tracks. Unfortunately, Mr. Flagler’s men did not fill every gap between the islands with viaducts or trestles.

Several gaps between the islands were closed using fill to create land to build the railroad tracks that delivered the train to Key West. In some places like Windley Key, the gaps were short enough that it was easier to fill them rather than to build a bridge to cross them. For instance, before Flagler’s men arrived, there were two islands in the Upper Keys called the Umbrella Keys. Once the railroad crew did their job, the narrow pass separating the Umbrella Keys was joined by fill to create a single island, recognized as Windley Key today.

Other railroad fill projects, like the one connecting Upper and Lower Matecumbe Keys, were of a grander design. The engineers created a land bridge between the two islands that measured 2.2 miles long. At the time, it is said that locals warned Flagler’s workers of the perils of essentially erecting a dam between the two islands. They knew what they were talking about.

One of the results of the causeway was that it obstructed the natural flow of water between the Atlantic Ocean and Florida Bay. One of its effects was that it redefined the shallows between the two islands and those surrounding the small 11-acre Indian Key located one mile offshore. Indian Key, by the way, was once the most important island in the Florida Keys not named Key West. One of its predominant features was a relatively deep, naturally occurring harbor. Thanks to the damming effect of the causeway, silt began to build up around the island, and the natural harbor filled up and disappeared. The causeway did other things, too.

When State Road 4A, the first version of the Overseas Highway, officially opened to traffic in 1928, it offered an incomplete road between Key West and the mainland. It was possible to drive a car from Miami to Key West, but the trip required a four-hour ride aboard an automobile ferry that departed twice daily, at 8 a.m. and 1 p.m. The road traveled through the Upper Keys and across the 2.2-mile causeway to Lower Matecumbe Key, where the road ended at the island’s west end. It picked up again 40 miles away at No Name Key.

The automobile ferry was not terribly convenient, and plans were made to build a series of concrete bridges between Lower Matecumbe and Big Pine to eliminate it. Hundreds of World War I veterans were brought to the Keys from 1934-1935 and housed in three work camps. Camp 1 was established on Windley Key. Camps 5 and 3 were created on Lower Matecumbe Key. The three camps housed 700. The influx of workers essentially doubled the population of the Upper Keys.

The year 1935 was a seminal year in the Florida Keys. It was Sept. 2, 1935 when the Category 5 Labor Day Hurricane ravaged the island chain and drove the final nail into the coffin of the Key West Extension of Henry Flagler’s East Coast Railway. That horrible Monday was the last time the train steamed, rattled and rolled down the railroad tracks hammered into the Florida Keys.

The eye of the Category 5 hurricane, the strongest ever to strike North America to this day, passed over Lower Matecumbe and Long Key. The storm killed hundreds of people, ravaged families and essentially erased the communities of Matecumbe and Islamorada from Upper Matecumbe Key. More than 200 residents and 200 World War I veterans were killed in the storm. While the true number of lives lost will never be known, it is thought to be in the neighborhood of 500.

While Flagler’s 2.2-mile stretch of railroad fill between the Matecumbe Keys was not a magnet that attracted the storm, it contributed to the devastation. Because the free flow of water that had historically passed between the Matecumbe Keys had become obstructed, the tidal surge pushed by the approaching storm piled up and piled up. With nowhere else to go, 17 to 20 feet of storm surge washed over the islands.

When the storm broke through the causeway and the water started to move between the islands, the water brought by the storm surge began dissipating as if someone had pulled the plug out of a sink filled with water.

Today, the original 2.2-mile-long railroad fill is augmented with four bridges.