On Windley Key, the highway travels 2.5 miles between its bridges. The island is home to some revealing stories.

However, to get there from the north, you must first cross the Snake Creek Bridge, the last drawbridge left in the Keys. The single-leaf bascule bridge, which opened in 1981, is run by a bridge tender who, once an hour, when needed, stops traffic and raises the metal grate so a boat can pass. The delay generally occurs at the top of the hour; it is not a prolonged event but rather a matter of a few minutes. The drawbridge operates from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. daily.

Windley Key used to be two islands. The 1772 DeBrahm chart identified the larger one as Wright. In 1849, Gerdes wrote in his pamphlet “Reconnaissance of the Florida Reef and all the Keys,” that the “Island between Long Id. (an early name for Plantation Key) and Old Matecumbe (Upper Matecumbe) has no name.”

In the 1850s, both a U.S. Coast Survey and a report for the U.S. Army written by Captain Abner Doubleday (yes, that Abner Doubleday, but he didn’t invent baseball) identified it as Vermont Key. During the construction of the railroad, the islands were known as the Umbrella Keys. The name Windleys Island was used, too.

While there is no clear history of the origin of the name Windley, it is thought to have come from an early pioneer. It was Henry Flagler’s men who, while building the Key West Extension of the East Coast Railway, filled the narrow channel separating the two islands with limestone, sand and marl until the two became one.

One thing that is not readily apparent while driving down the highway or across Windley Key is that the Florida Keys were once a thriving system of barrier reefs. What this island does best is provide a glimpse into its ancient history. The Florida Keys are a low-lying string of islands with an average elevation of 3.2 feet above sea level. At the Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park, there is a point registering a relatively staggering 18 feet above sea level, making it one of the highest points in the archipelago.

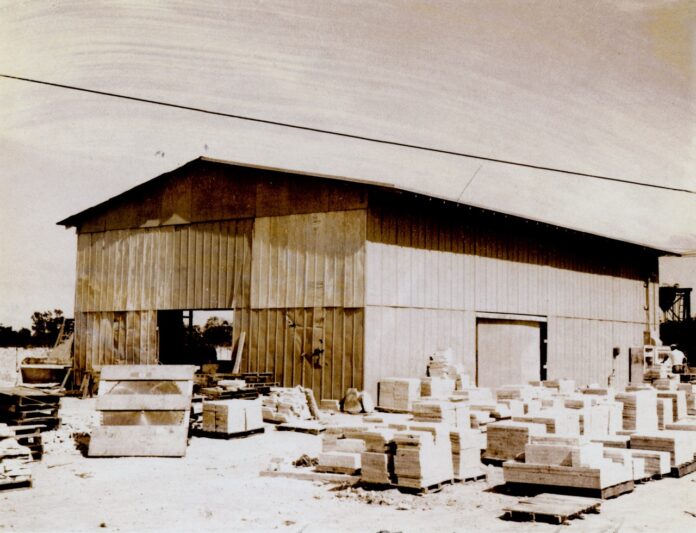

The park is aptly named. In 1883, Benjamin Russell homesteaded 127 acres of the substantially larger of the two islands. In 1895, the remaining 97 acres were deeded to the Jacksonville, Tampa and Key West Railroad network – a precursor to the Florida East Coast Railway. Both operated limestone quarries. Quarry work exposed 8-foot-tall island walls. Within those walls are the fossilized remains of the island’s beginnings as a coral reef.

When visiting the park and walking through the old quarry, some of the equipment used to cut through the limestone is still there. Interpretive panels explain the process. The real treasures are found in the exposed quarry walls. It is one thing to say that the island chain was built on the back of an ancient reef; it is another thing to see the fossilized coral evidence firsthand.

The last to work the quarry was the Keystone Rock Company. The quarrymen cut away slabs of limestone that were shipped to a Miami warehouse where the fossilized stone facades were polished to a sheen and sold as a decorative building material called keystone. The Florida Keys Memorial, also known as the Hurricane Monument on Upper Matecumbe Key, is an excellent example of keystone. Though keystone is still used, the keystone quarry ceased operations in the 1960s.

Not all of Windley Key’s quarries are located inside the park. A flooded quarry pit, created by Henry Flagler’s men on the other side of the highway, has been a venue for performing dolphins since the 1940s. Alonzo Cothron purchased the land with his partner, Berlin Felton. In 1932, the two were raising stone crabs in it.

P.F. “Bud” McKenney brought the dolphins. He leased the quarry and its surrounding acreage. With the help of Cothron, the property was developed into the 17-acre roadside attraction, Theater of the Sea. It was the second marine life-related attraction in the Florida Keys. The Key West Aquarium, one of President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration programs developed in response to the Great Depression, was the first.

When Theater of the Sea opened for business in 1946, admission prices were $1.50 for adults and 50 cents for children over 7. The park’s first performing dolphins were captured and trained by Grassy Key legend Milton Santini, considered a pioneer in the art of capturing, transporting and training wild dolphins. Santini’s most famous pupil was Mitzi, the dolphin best remembered for her role as Flipper, the star of television and silver screen. Today, Theater of the Sea offers not only educational shows featuring marine mammals but also opportunities to swim with the dolphins.

There is one more big event of a hallowed nature to address. After passing Theater of the Sea, there is a resort currently called Three Waters. Locals remember it as Holiday Isle. Back in the 1970s, John Egert was a bartender at its tiki bar. Most people called him Tiki John. One day, his manager challenged him to create a drink by using up some excess inventory. Tiki John started experimenting, and the winning drink was a combination of rum, lime juice, sugar, banana and blackberry liqueurs, mixed in a blender with a scoop of ice and served frozen. He called it the rumrunner; it is now world-famous and a part of many island vacations.

The original rumrunner did not have the reddish-pink hue it has today. The drink’s famous color came about after Tiki John ran out of sugar while at the bar and, improvising, reached for a bottle of grenadine. The sweetener used to make a Shirley Temple is not cherry-based but created from pomegranate.