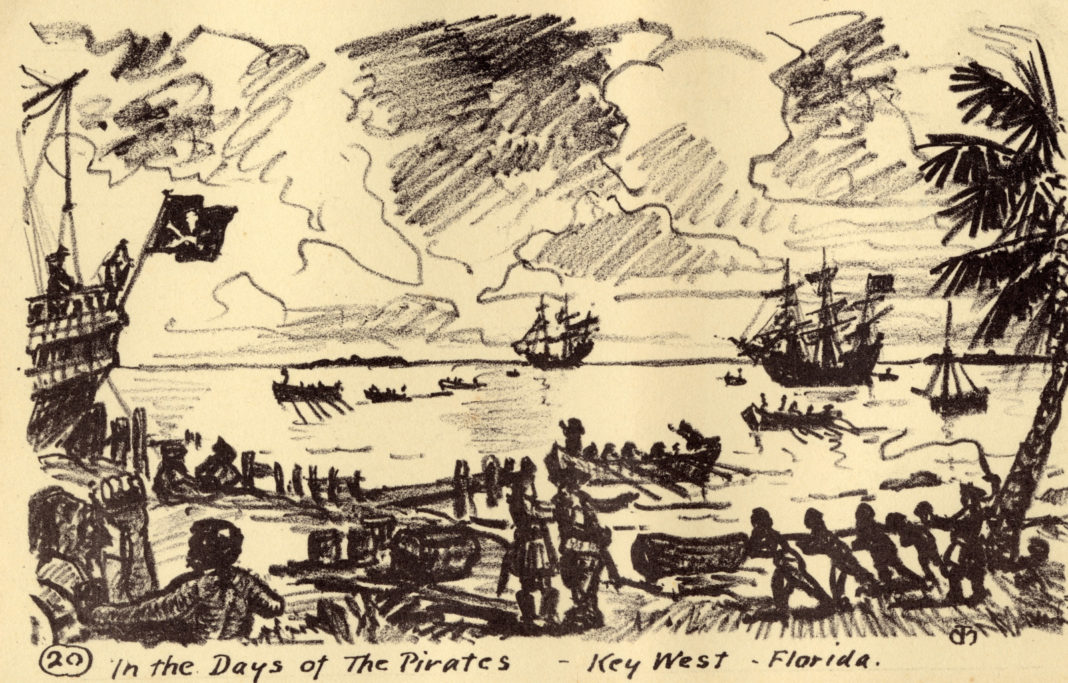

Editor’s Note: This is part one in a series on run-ins with pirates off the Florida Keys.

Pirate attacks on American ships sailing in foreign waters were nothing unusual in 1822.

The persistent problem was one of the reasons President James Monroe, on March 3, 1819, signed “An Act to Protect the Commerce of the United States, and Crimes of Piracy.”

The legislation allowed the U.S. Navy to establish the West Indies Squadron, a specialized force to combat both piracy and the slave trade, which the Navy did with great efficiency once Commodore David Porter was given command.

Even if documented instances of pirates are hard to connect to the Florida Keys, the history of the West Indies Squadron will always be connected to the island chain. Porter, the second to command the famed unit, made Key West his headquarters. In a general order issued from the USS Peacock on April 6, 1823, Porter wrote: “A Salute of 17 guns is to be find (fired) at 8 o’clock this morning from the Battery in front of the Town, and the American Ensign is to be hoisted at the Flag Staff… The Town is hereafter to be called Allenton, and The Battery, Thompsons Battery.”

The name Thompsons was chosen for the depot to honor the Secretary of the Navy, Smith Thompson. The name for the town developing on Key West, Allenton, was a tribute to a fallen member of the West Indies Squadron, Lt. William H. Allen, commander of the U.S. schooner Alligator. The Alligator was one of five swift ships of war built to arm the anti-piracy squadron. In March 1821, the schooner was commissioned. The events that led to the death of Lt. Allen on Nov. 9, 1822, resulted from a series of piratical attacks off the coast of Cuba.

One beginning to this story dates back to Sept. 18, when the master of the Ann Maria, home port New York, was navigating the waters near Cuba. The schooner was carrying, among other things, a cargo of salt. Before refrigeration, salt was a valuable commodity used as a preservative for food staples like pork, fish and other proteins. The schooner was also carrying at least one passenger, Mrs. Powell of Wilmington. On Sept. 18, Somers, the master of the Ann Maria, spied a schooner sailing out from the coast of Guajaba, Cuba. The schooner had a lead-colored bottom, a 12-pound cannon mid-ship, and four carronades (smaller cannons). Its intent was piracy.

Somers attempted to sail away from the pirates, but all he did was run the ship up on a shoal. With the Ann Maria compromised, the pirates boarded the schooner, secured the master, crew and Mrs. Powell, and went into business for themselves by selling the cargo of salt at cut-rate prices to ships sailing past. After three days, all the salt was gone and the pirates were seemingly done with the Ann Maria. Being the gentlemen that they were, the pirates worked to refloat the schooner. Once they set the ship free and sent the schooner on its way, the pirate captain suggested to Somers that he could restore his stocks with fresh cargo at the port of Matanzas.

Somers took the pirate’s advice, sailed to Matanzas, and took on stores of molasses and sugar before sailing away from the port and right into the awaiting arms of the pirate captain and crew they had just escaped. The ploy was a classic. A thief breaks in and steals all the valuables that can be sacked. The victim calls the authorities, a report is made, and an insurance company sends a check to replace the victim’s losses. Once the jewelry and other valuables are replaced, the thief returns to rob the joint all over again.

Shortly after sailing away from Matanzas, the pirates stopped the Ann Maria again. Instead of selling the cargo to passing ships, they brought the schooner and her crew to a small cove near Point Hicacos. According to Lt. Dale of the Alligator, part of the West Indies Squadron, the cove was located “about forty miles to the windward of this place.” “This place” was Matanzas, where the Alligator had arrived on Nov. 8.

The Alligator would not remain in port long. The master of the schooner Iris boarded and relayed to the Alligator’s commander, Lt. Allen that pirates were holding his ship and others for ransom. If he did not deliver $6,000 ($7,000 in some accounts) to the pirates the following day, his crew would be killed and his ship burned. Apparently, the pirates treated the good men aboard the Iris differently than the scoundrels who engaged the master and crew of the Ann Maria.

The fate of the crew of the Iris and how that story became entangled with the U.S. Schooner Alligator will be explored in next week’s edition of Florida Keys History with Brad Bertelli.