The year was 1975. I had just turned 10 when the Steven Spielberg classic “Jaws” came out. On a hot summer day, I sat in a dark, air-conditioned movie theater while the terrifying fish swam back and forth across the screen. I had a bucket of popcorn dripping with butter between my legs.

Suffice it to say, the film stayed with me long after the credits rolled. For the rest of the summer, I was afraid of the water. I would not wade into the ocean or jump in the waves at the beach. I still swam in backyard pools but was always a little nervous for a second or two when I jumped in. Once or twice, even the bathroom shower made me shake a little. I remember standing in the shower, warm jets of water hitting my head and dripping off my cheeks. I remember staring down at the shower drain and imagining a killer shark breaking up through the little silver cover. Stupid, right?

I had not yet read the Peter Benchley novel on which the production was based. Most people who saw the film had not. Benchley’s seminal tale pricked a fearful nerve in the collective conscience that demonized the species as a whole to a worldwide audience. While writing a great story, he portrayed the toothy fish as a cold-blooded killer, and it became some of the most dangerous shark fiction ever written. According to him, if he knew what the book would do, he never would have written it.

When I moved to the Keys in 2001 and started snorkeling around the coral reefs, I felt a sharky tug of apprehension in the back of my mind. It was absolutely irrational, but a dorsal fin pierced the surface of my subconscious.

The first time I saw a real shark was thrilling. I had seen nurse sharks swimming by or resting on the bottom, but nurse sharks do not have that classic shark design. My first experience with one of the big fish that looks like a sleek predator at the top of the food chain was with a Caribbean reef shark. It is not the biggest shark, and this one was about 5 feet long, but the fish swished its tail back and forth and swam low and slow over the shallow coral reef like a boss.

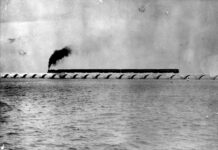

I posted about sharks on my Facebook group, Florida Keys History with Brad Bertelli, last week, and controversy erupted. It was a big picture to post, not for its clarity or resolution but for the rows of shark fins left out to dry on wooden tables. Back in the 1920s, Big Pine Key made a name for itself when it became home to the Hydenoil Products Company. Hydenoil was based out of New York and arrived on the island circa 1923.

The plant is said to have been located where Bogie Channel flows between Big Pine and No Name Key. A Miami News article, dated Nov. 16, 1930 and headlined “Shark Industry is Lusty One,” described aspects of the operation. According to the writer Cecil R. Warren, who interviewed the company’s Florida representative Mr. Eddy, Hydenoil planned to establish shark processing plants up and down the Florida coastline.

By 1930, the Big Pine plant had processed 20,000 sharks, including sawfish. Some 6,000 sharks had gone through the plant the previous summer. According to Eddy, nearly every part of the shark was used: “Hide for leather, liver for oils, fins for delicacies highly enjoyed by the Chinese, white meat for food, eyes and teeth for bead, buttons, and jewelry, bone for ornaments (sharks have cartilage, not bones), and dark meat and residue for chicken meal and fertilizer.”

After posting the image of the shark fins drying on the wooden tables, fishermen called for the practice to be brought back. Hunt down the sharks. Get them out of the water because the sharks were taking nearly every fish being reeled back to the boat. “It’s an epidemic.”

No one likes hearing from the IRS. However, sometimes you have to pay the tax man.

In most parts of the world, the tax man refers to an agency demanding their dues. For fishermen in the Florida Keys, the tax man comes dressed in a form-fitting sharkskin suit. Some fishermen, at least locally, are complaining about having to compete with sharks for the fish they have hooked.

The problem is threefold for the fishermen because you can’t blame a shark for being a shark. First, the sound of the boat’s motor churning through the water is a beacon. Second, when a fish is hooked, it wriggles and thrashes in the water in an attempt to break the line or the hook, and those are precisely the kinds of vibrations that alert sharks to the presence of vulnerable prey. Also, a fish biting a hook and struggling to free itself releases blood into the water.

According to NOAA, worldwide about one in four species of sharks and rays is threatened with extinction. Locally, the small-toothed sawfish is a species of critical concern, but it is not the only one. Apex predators, sharks play an essential role in the balance of the ecosystems where they live. Remove them from the equation, and the imbalance will begin to compound.

Sure, no one is saying cull them all, just enough of them to make it easier to reel a fish back to the boat. If you remove the inconvenience factor, live sharks contribute mightily to Florida’s economy. Based on a 2016 study, recreational divers and snorkelers seeking shark encounters brought $221 million into the Florida economy. The sale of shark fins nationwide brought in $1.03 million, making it clear that a live shark is worth more to the Florida economy than a dead one.

Playing the part of devil’s advocate, perhaps one of the reasons there has been more competition between fishermen and sharks is the pressure being put on the fisheries by commercial and recreational fishermen.