It’s gotten too hot in the kitchen. Or lack of a kitchen, rather.

The June 18 commission meeting took on the tone of Mom — aka Mayor Teri Johnston — getting home and taking the kids to task.

“The whole process stinks to the heavens,” said Johnston. “To still be having the same conversation is reprehensible.”

It’s a bizarre Mallory Square restaurant saga that’s been cooking for nearly 10 years. Restaurateur Joe Walsh, the man behind Caroline’s and Jack Flats, among other ventures under the Tropical Soup Corporation name, has been back and forth with the City of Key West and the Historic Architectural Review Commission (HARC) for 10 years about his proposed restaurant on Mallory Square. Walsh, who has revised his plan “dozens” of times on request of the city and HARC, has a problem: the lack of a kitchen in the 150-seat restaurant. Commissioner Jimmy Weekley has argued that the plan doesn’t match the original RFP, which included a museum, green space and two-story restaurant with kitchen.

The plan Walsh has put forth (which was signed off on by city manager Jim Scholl two years ago) does not include a conventional kitchen. However, Walsh is at the helm of — and majority owner of — five restaurants in Key West, enabling him to prep and deliver from other locations. Folks on both sides of the aisle have called the process a “nightmare.” Walsh’s timeline of the nightmare, in the form of an attachment to the agenda for the June 18 commission meeting, was seven pages long.

A vast simplification of this nightmare?

In 2010, the city selected Walsh’s RFP for a two-story restaurant, out of 16 applicants. In January 2011, the city approved the preliminary plan, and the Westin (now Margaritaville) began litigation to oppose development. Tropical Soup drew up new plans. The city manager authorized Walsh to move ahead with those plans in May 2015. Fast forward to 2016: HARC denies the plans and asks for significant changes, which Walsh makes. HARC denies the new plans again, and Walsh appeals the decision to a special magistrate. Walsh wins. In 2017, the city appeals the decision, but it’s upheld.

In 2017, City Manager Jim Scholl signed off on Walsh’s plans that are, for all intents and purposes, the same as what he now proposes. The project was up for approval before the commission, but then Tannex (aka the Westin aka Margaritaville) contacted the city with myriad concerns, including, but not limited to, the lack of a conventional kitchen in the new plans.

Truly: the plan Walsh has put forth relies heavily on delivery from his other restaurants, making it difficult, in the eyes of Weekley and City Attorney Shawn Smith, among others, to lease to another renter if the agreement does not work out with Mr. Walsh.

“Once you reduce the scope and are limited to delivering food in, you are limited in renters,” said Smith. “If you get to the point where you want to renew the lease, you have to have someone who has the ability to shuttle food in and out.”

“It’s 150 seats for a full bar, so he can use his other location to cater,” said Weekley, who sponsored the resolution to cease lease negotiations with Walsh. “It puts the city in a situation where we won’t be able to do anything with the property, if the relationship sours.”

Bart Smith, the attorney representing Margaritaville, who has initiated litigation to kill the project for the last six years, said, “We are dealing with a bar that delivers food. It isn’t a restaurant or museum.”

“Terminate it today,” he asked.

Johnston was nearing the bounds of her patience with the process, fingering the city, the planning board, the city manager and Margaritaville all as culpable parties for the nightmare that it’s become. Johnston said all Margaritaville “wants to do is litigate,” and they had every opportunity to put up an RFP nearly 10 years ago.

“Mallory Square continues to fall into a state of disrepair. We can only attract the lowest cruise ship with the most reprehensible environmental record. This applicant has jumped through every hoop,” she said. The mayor further cited the $303,000 in annual revenue Walsh has committed to the city as a condition of the lease, which has been lost every year this process has dragged on.

“It was poorly handled and orchestrated by the city,” she said. “When we’re at fault in a situation, we need to take responsibility.”

The other issue of contention?

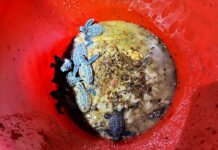

The historic cable tanks, which were the source of much of HARC’s dispute with Walsh’s plans. The tanks are holdovers from the 1920s and 1930s, when they were used to store equipment for telecommunications. The cable hut by the Southernmost Point—from which a 125 telegraph line to Cuba originated—is restored and has a historic plaque explaining its purpose. However, the cable tanks in Mallory Square have fallen into a state of disrepair.

Walsh has plans to restore Cable Tank 2, as part of one of the parcels on which his restaurant would be built. He plans to retain the historic elements and even include restaurant seating inside. Cable Tank 1 is not subject to this proposed lease.

Walsh said he is still maintaining fealty to the original RFP: a museum is still in the proposal and a park that is still in the proposal. He cites multiple meetings with city staff, and says that the removal of the larger kitchen space was requested by the city staff and planning board. He also maintains that the city and Margaritaville are responsible for years of litigation.

Johnston and Commissioners Gregory Davila, Samuel Kaufman and Billy Wardlow seem to agree: they all voted to move ahead with the project and move onto contract negotiations.

Said Davila: “He won. It would be patently unfair at this point in the game to pull the rug out from under the process and not hear the merits of the project.”

Walsh may finally now have his day in the sun (or in the square), a decade in the making. His vision includes the 150-seat restaurant and bar, seating in the historic cable hut, a green space and overall cleanup of the Mallory Square area, anchoring the space opposite El Meson de Pepe.

“It’s a crown jewel of Key West,” Walsh said, “and the city ignores it. … There’s no benches, public art, no trees.” The commission also has expressed a commitment to downtown revitalization, and the mayor is on board. The project will be back up on the agenda for the July 16 meeting to move toward a lease. Citizens will see how the face of Key West’s most famous square might change as Walsh’s restaurant project makes its way through the corridors of Key West bureaucracy.