An aerial view of the Florida Keys’ beauty is one to behold, with different shades of blue wrapping around historical lighthouse structures, sandbars, bridges and the island. Bird’s-eye shots of the Keys can also raise eyebrows, as evidenced by aerial photographs of scattered lines through seagrass beds near one highly-known channel.

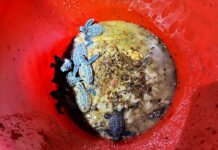

More boats taking to the waters and sandbars, like the one off Whale Harbor, means more instances of seagrass bed scarring from boat propellers. Look no further than a photograph taken in 2018 and another just three years later at Snake Creek Channel by David Gross, coxswain with the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary in Islamorada.

A few noticeable streaks are seen in a 2018 shot, but those lines multiplied in a year coming off exploding boat sales and more people on the water due to a coronavirus pandemic.

Damage to seagrass could increase with more boats on the water, say officials with NOAA”s Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. However, with targeted management, boater awareness and compliance to rules and regulations, seagrass resources are resilient and can recover from prop scarring.

Officials with the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary say prop scar occurrences are definitely proportional to the number of the boats on the water. Ignorant boaters and out-of-town visitors aren’t only to blame for groundings and scarring seagrass beds. Recent groundings have also included commercial shrimpers and local fishermen trying to take shortcuts, officials said.

But NOAA’s Bill Goodwin said that based on having documented scores of seagrass groundings, unfamiliarity with local waters is the leading factor.

“Chronic prop scarring of many areas is more than likely the result of boaters taking shortcuts and ignoring channel marking,” he said. “Groundings of local commercial vessels are few and far between.”

“If there is any common foundation to groundings, it may simply be a lack of knowledge and appreciation for the function and value of seagrass beds,” said Lindsey Crews, science and outreach program coordinator with the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Propellers have scarred a majority of seagrass beds in South Florida. When a boat’s propeller hits seagrass, it fragments the seagrass meadow and can lead to excessive erosion and further loss of seagrass habitats. This can limit the movement of animals living in this habitat, leaving barren areas where fish and other marine life once flourished.

From Bahama sea stars and egrets to sea turtles and queen conch, seagrass beds are among the most fertile habitats in the Florida Keys, Crews said. More than 80% of the species caught by commercial and recreational fisheries in the Keys relies in some way on seagrass.

“The blades slow water flow, allowing silt and sand to fall out of the water,” Crews said. “This creates the crystal clear water needed for coral reefs to thrive. Seagrasses stabilize sediments on the seafloor, filter pollutants and absorb excess nutrients from runoff.”

NOAA officials say it can take many years — even decades — for prop scars and blow holes to recover. Any scarring below 20 centimeters needs to be filled with sediment, as roots can’t grow downslope.

“Unlike many of the plants that grow in your garden, seagrass roots, or rhizomes, grow horizontally along the sand, and not straight down into the sediment,” said Crews. “Deep scarring or blow holes made by powering off of shallow areas must be filled in with sediment before restoration can truly begin.”

NOAA officials usually get notified of scarring related to a vessel grounding case by the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission.

“We pretty much are the first responders,” said FWC Officer Bobby Dube. “We usually mark the area and document it and submit a report to the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.”

Most cases are assessed within weeks to months from the incident. Restoration takes considerably longer, however, and rarely occurs until NOAA receives a settlement from the responsible party. If a case goes to litigation, it can take more than a year to resolve.

The National Marine Sanctuary Act provides for civil penalties up to $178,338 per violation, per day. The law also provides for the ability to seek damages for the cost of assessing the injury, developing a restoration and monitoring plan and the implementation of those plans. Costs are based on the actual cost for restoring an injury.

Since 2010, NOAA Office of General Counsel Enforcement Section has issued numerous penalties for vessel groundings ranging from written warnings to $18,000. Factors used to determine an appropriate penalty or permit sanction include the nature, circumstances, extent and gravity of the alleged violation; the alleged violator’s degree of culpability; the alleged violator’s history of prior offenses; and the alleged violator’s ability to pay the penalty.

Where resource injuries are significant, FKNMS can seek cost recovery associated with restoring sanctuary resources that were injured. Working with the Department of Justice, NOAA General Counsel Natural Resources Section recently settled a case where a vessel grounding resulted in injury to over 1,700 square meters of seagrass habitat. The fines included just over $70,000 for assessment costs incurred by NOAA and $2.1 million for costs associated with restoration and monitoring.

NOAA officials say creation of idle speed or no motor zones has proven beneficial in allowing seagrass recovery — Tavernier Key being a prime example. In images from 1995, these seagrass flats exhibited a high level of seagrass scarring prior to implementation of a no motor zone in 1997. Repeat imagery taken in 2017 showed significant recovery.

These changes indicate that with targeted management and boater awareness and compliance, seagrass resources are resilient and can recover from prop scarring damage.

NOAA is proposing new vessel speed and access restrictions in wildlife management areas within its Restoration Blueprint. A draft rule, which includes an updated proposal, will go out for public comment later this year.