Scientists hot on the trail of the root cause behind unprecedented sawfish deaths and spinning fish throughout the Florida Keys say they don’t have all the answers yet. But thanks to new information unearthed in a massive collaborative effort over the last three months, they could be on the right path.

An hour-long March 20 live stream conducted by the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust (BTT), one of several organizations on the front lines in combating the strange phenomena, provided arguably the most substantial public update so far, pairing BTT biologist Ross Boucek and vice president Kellie Ralston with Michael Parsons, director of Florida Gulf Coast University’s Vester Field Station, and the University of South Alabama’s Alison Robertson. Other leading collaborators include the Lower Keys Guides Association (LKGA), Florida International University, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC).

Boucek outlined four “lines of inquiry” that began in January 2024 after reports of spinning fish began in October 2023 and seemed to intensify in December: potential contamination from human-generated sources, such as wastewater effluent or pesticides; evidence of degrading fish health metrics, possibly indicating long-term illnesses or high loads of pathogens or parasites; contaminants stemming from the water column, including red tide; or toxins stemming from the sea floor.

So far, Boucek said, 25 research missions since mid-January including 30 biologists and 12 fishing guides have yielded 150 fish samples, 200 water samples and more than 200 substrate samples, along with more than 200 reports of symptomatic fish – all but two of which originated from inshore waters.

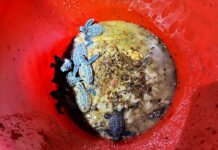

“The reports cover 35 different species from forage fish to game fish, sharks, rays and everything else in between,” he said. “Whatever this is, it does not discriminate based on species size, migratory pathways or behavior.”

Narrowing the focus

While some were quick to point to human waste or pesticides as news of the event spread, Boucek said that at the time of the live stream, partners including DEP had yet to identify any elevated levels of human-generated contaminants in Keys waters. Similarly, fish health metrics from assessed samples are normal, and water chemistry parameters including salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH and temperatures show nothing out of the ordinary. FWC scientists have yet to find elevated levels of the algae causing red tide in Florida (Karenia brevis), or the toxins associated with this algae, in the collected water samples, Boucek and Robertson said.

So what’s unusual?

The team’s first lead, Parsons said, came from elevated levels of a family of algae known as Gambierdiscus detected in the water column in areas with affected fish, as well as in the gut contents of some affected animals.

“It’s a benthic species, so seeing it in the water is a little unusual,” said Parsons, who added that abundances of the organisms were “anywhere from five times higher to about 30 times above averages we’ve seen over the past 10 years” near seagrass beds with fish exhibiting the erratic behavior.

“The maximum numbers we saw were below 10,000 cells per liter of water,” Parsons added. In that concentration, he said, the algae won’t trigger a visible color change in the water, as commonly observed with red tide. “That (number) is a lot for Gambierdiscus, but it’s not a lot in terms of our typical blooming species. So that’s one reason why Gambierdiscus was kind of under the radar here.”

An umbrella term for a genus that includes more than a dozen individual species, Gambierdiscus abundance has historically been linked to recently-impacted areas of coral reefs through an increase in ciguatera poisoning. Caused by potent toxins known as ciguatoxin and maitotoxin, both of which can be produced by Gambierdiscus species, the acute illness can include symptoms of diarrhea, vomiting, numbness, dizziness and weakness for those who ingest fish with accumulated toxins.

“The higher-than-normal water temperatures that we saw down in the Keys (last summer) could have perturbed the system in such a way that Gambierdiscus is now at an advantage,” Parsons said. “We’re trying to put the pieces of the puzzle together there and looking for clues at the scene of the crime.”

Ironically, Parsons said, the thing that may have put the harmful algae at such an advantage may also be the thing to eventually suppress it, as Gambierdiscus numbers tend to peak in the fall and winter months before dropping in the heat of the summer.

“The irony here is, did the hot summer cause what we’re seeing now? But this coming summer may actually suppress the Gambierdiscus population,” Parsons said.

Localized origins give clues about toxins

Though reports of affected fish have now spread throughout the Keys, “(the symptoms) have lingered in the central spots for a while,” said Robertson. “That gives us some information that whatever this issue is, it may have been on the bottom.”

So far, toxins produced by Gambierdiscus have been detected in “reef-associated” fish samples and bottom-dwelling algal samples studied by Robertson and her team. Also detected were levels of okadaic acid, a toxin produced by another dinoflagellate that’s more commonly associated with shellfish in northern latitudes, and a few other “novel compounds” still under study. While the presence of these toxins themselves aren’t the “smoking gun” that researchers have been searching for, she said, “we could be looking at the fact that those background levels (of toxins) might make fish more susceptible to whatever is causing the spinning.”

Though seldom mentioned in coverage of the event thus far, spinning fish have been shown to recover in some cases when moved to clean water, supporting the idea that whatever causes the spinning behavior is in the water column and crossing the gills of affected fish, Robertson said. The symptoms reported in these fish, she said, are consistent with neurotoxins produced by algae.

Robertson’s team has been working “seven days a week, 12 to 14 hours a day” to grow neuronal cells and expose them to any possible chemical extracted from Keys water samples, algal samples or fish tissues, searching for evidence of cellular disruption or death.

Is it safe to eat fish and swim in the Keys?

Both BTT and FWC’s online dashboards to address the abnormal event recommend avoiding eating symptomatic or already-deceased fish, as well as fish harvested from areas where other affected fish are observed. Both say to avoid swimming in areas with dead fish.

What’s next?

Boucek, Parsons and Robertson all stressed that while investigators are following “the strongest lead” while avoiding “cold dead ends” in ongoing research, a definitive cause-and-effect relationship has yet to be established.

“We haven’t solved this,” said Parsons. “(Gambierdiscus) seems to be the most promising lead, so that’s where we’re putting in a lot of effort.”

Upcoming experiments, Parsons and Robertson said, will continue to identify species of Gambierdiscus present in Keys water samples, as well as investigate sediment samples to try and identify biological or chemical markers of past disturbances in the Keys’ marine ecosystem. Expanded sampling through time outside of known affected areas should help in better understanding the spread and boundaries, if any, of the phenomenon. Meanwhile, controlled experiments exposing fish from unaffected regions to Keys water samples or individual toxins will attempt to reproduce the behaviors seen in the wild.

“As we look at these samples, we’re trying to be open-minded about what the cause might be,” Robertson said. “Mike and I have a lot of very focused individuals, and we’re not going to give up.”

BOX OUT:

What can we do?

- Turn off the lights. While many on social media have been eager to venture out at night in search of symptomatic fish, “shining a flashlight on a fish that’s seemingly healthy before the light hits it can cause this seemingly erratic behavior.” Boucek said. Avoid shining flashlights in the water, especially in regions known for symptomatic fish.

- If the fish are spinning, keep moving. Catch-and-release fishing seems to trigger symptoms in affected fish, Boucek said. If caught fish are spinning after they’re released, move to a new area. Investigators’ initial work has shown that distances of less than a mile can yield vastly different fish behavior.

- Make official reports of affected fish or discolored water. While social media posts have helped to spread awareness, if fish are spinning or distressed or anglers see areas of discolored water, researchers need to hear through official channels. Scan the attached QR codes to make an official report through the Lower Keys Guides Association or FWC’s Fish Kill Hotline (800-636-0511). To report sawfish in distress, call 844-472-9347.

- Watch the live stream. Scan the QR code to watch BTT’s full March 20 live stream.

- LINK: https://www.facebook.com/bonefishtarpontrust/videos/426653396529960

Donate to continued research. Initial event response funding provided by NOAA, along with $2 million included as a last-minute addition in Florida’s state budget set to take effect July 1, have aided in funding a continuous research response. Additional donations to fund immediate continuation of research may be made at www.bonefishtarpontrust.org/donate/.