MARATHON

Joshua Appelby sailed from Rhode Island, bound for the West Indies, circa 1822. He would come ashore in the area of Knights Key with a partner, John Fiveash. The two established Port Monroe. The community earned a reputation for operating beyond the scope of territorial law and attracted the attention of Commodore David Porter, in charge of the anti-piracy unit assigned to secure the waters of the West Indies.

Porter wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, “I am under the impression that the practice of wrecking Spanish vessels on the coast by Columbian cruisers, in order to secure their cargoes, has, for a long time past been pursued to a considerable extent, and that the establishment at Key Vacas was made with this object in view.” Appelby was subsequently arrested. He would return to the Keys and, in 1837, accept the position of keeper at the Sand Key Lighthouse. The lighthouse was destroyed in the Great Havana Hurricane of October 11, 1846. More than 250 people died, including Appelby, 77, his daughter, 51, and grandson, 11.

Today, Appelby is largely remembered through the Keeper-class United States Coast Guard cutter named after him. The Joshua Appelby was the sixth of 14 Keeper-class cutters, named after lighthouse keepers, and commissioned August 8, 1998. Not every dubious mariner has been remembered so fondly.

KEY WEST

John Jacob Housman left Staten Island, New York, bound for the West Indies, in 1822. After his schooner William Henry struck the Florida Reef, he stopped at Key West for repairs and was introduced to the wrecking industry. By 1825, Captain Housman had been engaged in the wrecking industry for several years. He is remembered as a notorious Florida wrecker and not well liked in Key West as the events of September 1825 reveal. After word reached Key West of a salvage operation undertaken by Housman, Fielding A. Browne, who would become Key West’s second mayor, levied charges stating that Housman “defied the civil and military authorities of this place to proceed to Charleston to dispose of his cargo.”

John Jacob Housman left Staten Island, New York, bound for the West Indies, in 1822. After his schooner William Henry struck the Florida Reef, he stopped at Key West for repairs and was introduced to the wrecking industry. By 1825, Captain Housman had been engaged in the wrecking industry for several years. He is remembered as a notorious Florida wrecker and not well liked in Key West as the events of September 1825 reveal. After word reached Key West of a salvage operation undertaken by Housman, Fielding A. Browne, who would become Key West’s second mayor, levied charges stating that Housman “defied the civil and military authorities of this place to proceed to Charleston to dispose of his cargo.”

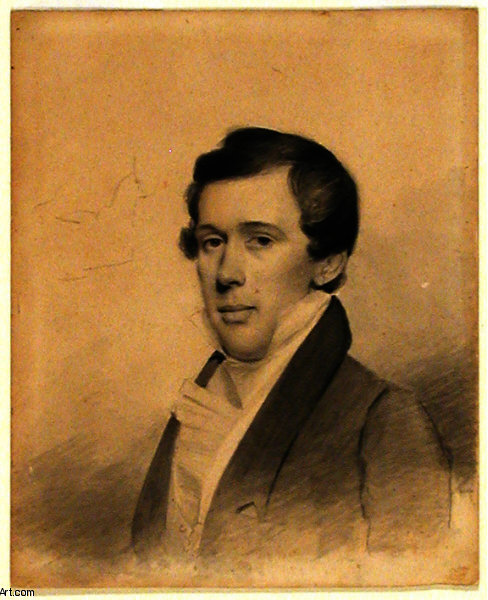

Browne went so far as to compel Captain Brown of the U.S. revenue cutter Florida to chase Housman down and place him under arrest. Housman only heard of the charges after pulling into port at St. Augustine to declare his cargo. Salvaged goods could be taken to Key West or St. Augustine. Housman fired back at Browne that he should “take another occasion to lay before the public, a history of the impartial and disinterested conduct of the gentlemen of many avocations at Key West, in their disposal of property falling under their control, and it will then be fairly understood whether there was more wisdom or folly in my giving preference to a decision at St. Augustine over one at Key West.” Brad Bertelli is curator of Keys History & Discovery Center. Painting of John Jacob Housman by John Wesley Jarvis.

UPPER KEYS

The Florida wreckers are generally cast in an unflattering light and considered little better than pirates as this 1790 story printed in the Georgia Gazette revealed: “The wreckers (Bahamians) generally set the ships on fire after they have done with them, that they might not serve as a beacon to guide other ships clear of those dangerous shoals.” Wrecking reform brought rules and regulations to the wrecking industry and while there are bad apples in every profession, the Florida wreckers were often the first responders of their day for those aboard ships that had crashed on the reef.

The Florida wreckers are generally cast in an unflattering light and considered little better than pirates as this 1790 story printed in the Georgia Gazette revealed: “The wreckers (Bahamians) generally set the ships on fire after they have done with them, that they might not serve as a beacon to guide other ships clear of those dangerous shoals.” Wrecking reform brought rules and regulations to the wrecking industry and while there are bad apples in every profession, the Florida wreckers were often the first responders of their day for those aboard ships that had crashed on the reef.

In 1837, the Charleston Courier published a story by Dr. Benjamin B. Strobel, a physician and writer who traveled extensively through the Keys, that read, “From all that I heard of wreckers, I expected to see a parcel of low, dirty pirate looking crafts, officiated and manned by a set of black whiskered fellows, who carried murder in their very looks.”

Dr. Strobel added, “I was, however, very agreeably surprised to find their vessels fine large sloops and schooners, regular clippers, kept in first rate order, and that the Captains were jovial, good humored sons of Neptune, who manifested every disposition to be polite and hospitable, and to afford every facility to persons passing up and down the Reef. The crews were composed of hearty, well dressed, honest looking men.” Brad Bertelli is curator of Keys History & Discovery Center. Photo courtesy of Jerry Wilkinson Collection.

— BRAD BERTELLI, Curator Keys History & Discovery Center