Fish are under pressure — a lot of it.

Over the past several decades, the fishing industry has undergone a remarkable transformation. Whether it be the use of GPS-controlled self-anchoring trolling motors, the widespread adoption of multiple outboards on offshore rigs, or even the use of sophisticated sonars, technology has skyrocketed in the industry, allowing anglers, new and old, more access to fisheries than ever before. Add social media and a newfound influx of fishermen into the mix, and you get an exciting yet scary reality —fish have nowhere to hide.

When you consider ease of access and an increase in the number of fishermen, it’s no surprise that many species of fish are being caught more now than ever before — fun for the fishermen but not necessarily fun for the fish.

In many ways, the United States has responded to this reality by devising management frameworks that promote sustainable harvest while also supporting the future of the fishing industry — commercial and recreational.

While that appears to be great news for the future of our oceans, the story is a bit more complicated. Despite monumental management and stakeholder efforts to ensure sustainable fisheries, data still show struggling fish populations in many offshore reef ecosystems.

Something doesn’t quite add up.

There’s a growing problem coming to the forefront of reef fisheries conservation, and it’s one you might not have considered — catch-and-release.

The formal term is “discards.” These are fish that are released due to any number of factors — seasonal closures, size limits, marketability, etc. Discards are a growing concern in the fishing industry largely because many of these fish die after being released. This “discard mortality” has emerged as a serious problem, particularly in offshore reef fisheries. These fisheries need a solution and one quickly.

Enter best fishing practices.

These are measures anglers can take to improve the chances that the fish they release survive to live another day. These practices aren’t foolproof, but they give each fish its best shot at survival.

This past January, my colleagues and I collaborated with Key West’s Gulfstream IV headboat to document and share a few best fishing practices that reef fishermen can implement next time they are out on the water.

The wind was sweeping over the Keys out of the south that day, pushing us to target several patch reefs about 15 miles offshore. After about an hour run to the fishing grounds, we slowed down and prepared for our first drop.

As soon as the boat anchored, we baited up our rigs and dropped down to the bottom. We were met with non-stop action. The first fish in the boat was a lane snapper — named for its lateral yellow, broken stripes.

We were using cut squid or ballyhoo (a local baitfish) on non-offset circle hooks. The use of non-offset circle hooks is an easily adoptable best fishing practice that can have enormous impacts on the survival rates of released fish. Unlike many other hook types, non-offset circle hooks have a unique rounded design that facilitates consistent hooksets in the corner of the jaw.

Not only do jaw hooksets make unhooking the fish easier for anglers, but they minimize the hook trauma a fish experiences. Even better, they do so without compromising catch rates.

Using other hooks can increase the odds of hooking a fish in a more lethal area like the throat, gills or stomach. In many regions, circle hooks have become mandatory to use in an effort to reduce discard mortality.

After a handful of lane snapper were caught and quickly released, a few other species began to show themselves. Among those were several groupers including red grouper and the smaller graysby. With these shallow water groupers out of season, every individual needed to be released after a quick picture. When posing for a picture or unhooking a fish, there are a few best practices to consider.

For starters, it is critical to avoid contact with sensitive areas like the gills and eyes. Additionally, and especially for larger fish, supporting the body horizontally is key. Fish experience gravity underwater, but the water pressure helps support organs from all sides. Once a fish is brought out of the water, that body support goes away. Ideal handling practices include holding the fish horizontally, supporting the stomach with one hand, and grabbing the tail with the other.

In addition to hook selection and proper handling practices, another best practice we implemented was looking for barotrauma. Barotrauma is a condition many deep water fish experience when they are pulled to the surface. Their gas-filled organ, the swim bladder, quickly expands with the decrease in water pressure, causing all sorts of negative side effects related to organ displacement. Most notably, affected fish typically float at the surface after being released, decreasing their chance of survival. Common symptoms of barotrauma include the stomach protruding from the mouth, eyes bulging, and bloating.

As fishermen, it is critical to be on the lookout for signs of barotrauma and treat symptomatic fish accordingly. Anglers can do so by using descending devices or venting tools. Descending devices are weighted tools that bring fish back to depth, recompressing the swim bladder whereas venting tools are hollow needles that, if used correctly, puncture the swim bladder and allow gas to escape.

For more information on symptoms and treatments of barotrauma as well as other best practices anglers can take on the water, check out this guide on Best Fishing Practices.

While the aforementioned release practices are critical in supporting the future of your fisheries, it is just as important to document when you use these practices. Documenting your best practices gives scientists a better understanding of the probability of survival for released fish.

For example, consider a fish that is deep-hooked in the stomach with an offset j-hook. This fish is also experiencing barotrauma symptoms, namely bloating, but is not treated with a descending device or venting tool. This fish has a much lower chance of surviving than a symptomatic fish that is hooked in the jaw with a non-offset circle hook but sent back to the bottom using a descending device.

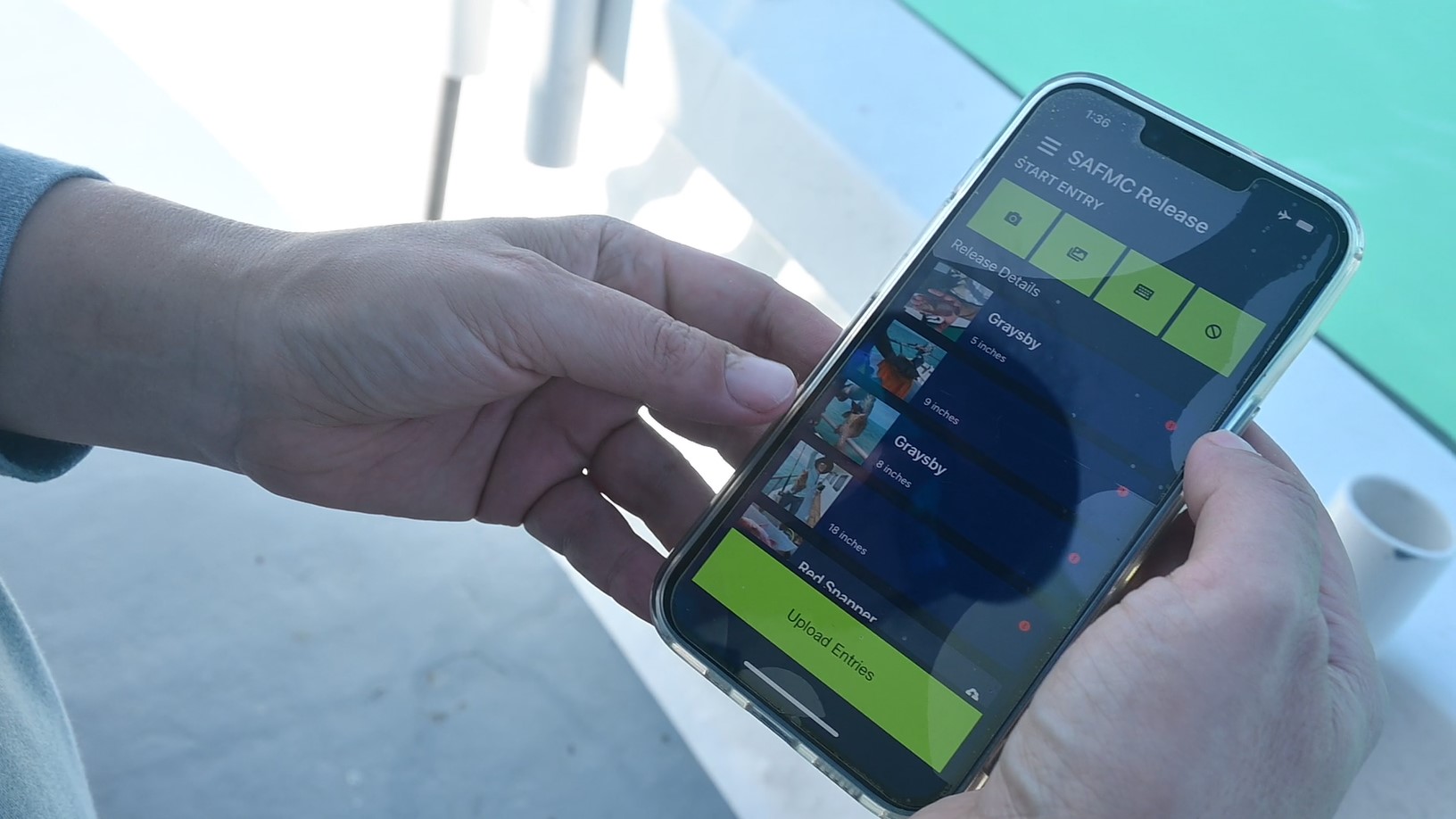

The South Atlantic Fishery Management Council (SAFMC) has developed a citizen- science project called SAFMC Release which partners with fishermen to log information related to their released shallow water grouper and red snapper. Through the free app Sci-Fish, anglers can add data on catch details such as fish length, hook location, and descending device use. The goal is for these data to be analyzed and results to be incorporated in future management decisions. The takeaway — your on the water knowledge provides valuable insight into your snapper grouper fishery.

You can learn more about SAFMC Release here.

David Hugo is the new South Atlantic Reef Fish Extension and Communication Fellow, working with Sea Grant programs in the Southeast and the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council.