I was reading a species account of the Reddish Egret the other day, when the authors described the bird as a “charismatic species,” which kind of stopped me in my tracks. Charismatic?

A species account is basically the scientific lowdown on a bird – what it looks like, where it lives, what it eats, its sexual proclivities – all that good stuff. This one was in “Birds of the World” produced by the heavy hitters at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Not the kind of people who throw around admiring superlatives willy nilly.

Was there a technical usage of charismatic that differed from how you would use it to describe, say, George Clooney?

The term was in the introduction, just after a long section quoting John James Audubon’s description of the first time he saw Reddish Egrets, which was here in the Florida Keys.

The birds were in the distance, but Audubon’s hired guide told him, “you may soon see them close enough, as you and I will shoot a few by way of amusement.” And then they shot more than a dozen and got closer looks. (In his defense, Audubon did need to study them to paint them, and there were no binoculars at the time.)

Anyone who’s read a lot of contemporary writing about animals has heard the term “charismatic megafauna.” The concept gets thrown around in environmental and conservation biology circles to describe large critters that garner a lot of public interest, sympathy and oftentimes, donations. Think pandas, elephants, tigers, whales… Animals that are often used as the standard bearers of the (usually threatened) ecosystems in which they live. Animals that also usually make good cartoon characters.

A bit of research (fine, Googling) took me down a rabbit hole that led to the conclusion that a charismatic species is not an empirical term. In my travels I did, though, run across an excellent paper in which the authors tried to make science by nailing down a more precise definition of the term.

They also created a ranking of the top 20 charismatic animals in the world, based on surveys of the general public, as well as assessments of how they were portrayed in zoo advertisements and posters for Disney and Pixar movies, with their charisma score based on how rare, endangered, beautiful, cute, impressive, and/or dangerous they were. Tigers just beat out lions to come in at the top (I doubt we’d know the names Carole Baskin and Joe Exotic if they raised iguanas). Whales came in at number 20. It was an interesting exercise, but I call bullshit because the list did not include any birds. Any list of the most charismatic species that doesn’t at least include penguins is obviously cripplingly flawed in its methodology.

Now that we know “charismatic species” is a subjective descriptive, the next question is why the Reddish Egret is considered so compellingly charming. To anyone who has seen them in action, the answer is glaringly obvious: It’s their dance moves.

A lot of birds have dance moves. Male and female Sandhill Cranes perform these high-speed, call-and-response ballets. Western Grebes run side-by-side across the surface of the water, wings back, in matching anime ninja postures. (See: Naruto. Or just see Western Grebes.)

Male Bearded Manakins – actually, the males of a lot of manakin species – lounge about all day at rainforest leks, which kind of function like dance halls, and wait for female manakins to stop by, so they can compete to impress them with their leaps and wing snaps. The victor goes off into the bushes with the female for a couple seconds to exchange genetic material. That’s pretty much all male Bearded Manakins do with their lives.

But all these birds are dancing for – let’s call it romance. Reddish Egrets – which are sometimes reddish and sometimes white – do perform courtship dances that involve leaping over each other, circling around each other, handing each other twigs, and emitting what Audubon described as “hollow rough sounds.”

But they only do that a couple times a year. They perform a daily dance for a different audience: fish.

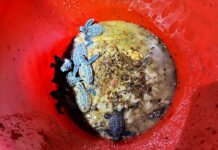

In the Keys you mostly see Reddish Egrets in shallow saltwater ponds or out on the tidal flats. Their dance floors tend to be mud covered by two to six inches of water.

Usually it starts with a run. Then maybe a change of directions. Then a wing fake, or a head fake, or double wing fake. Then maybe a leap into the air and a look-at-me landing. Sometimes they’ll run with their head canted 45 degrees to the side. Sometimes they’ll fluff out the feathers on their neck to make themselves look bigger. It’s a full body commitment, all arhythmic, improvised, high energy, maybe a touch over-dramatic.

Imagine viewing something choreographed by Martha Graham or Alvin Ailey with the sound off. Throw in a tablespoon of the landlord’s interpretive dance quintet from the “Big Lebowski.”

It is, in fact, damn charming to watch.

The point, of course, is not to entertain the fish, but to scare them, confound them, confuse them. To keep them from knowing when a bill might stab into the water and grab them up.

Dance is life for some. Though, maybe not if you’re a fish.