William Earl Dodge Scott and John Wyley Atkins must have had some interesting correspondence, as evidenced by a letter Atkins once sent to Scott.

“I will send you shortly the head of a Key West Quail-dove (Geotrygon martinica). The Dove was shot here (Key West) by a boy on Dec. 8, 1888, and was brought by him to the telegraph office to show me. Unfortunately I was absent. When I returned, one of the office boys told me of the ‘red dove.’ Going in search I found the Dove had been sold with some Carolina Doves to a man near by. l arrived at his place to find that it had been picked with the others, and only succeeded in obtaining the head and some wing and tail feathers,” Atkins wrote.

The bird parts actually turned out to be from a ruddy quail-dove, which was actually a good bit rarer than a Key West quail-dove, which was pretty rare in itself.

Scott started out as a boy with a limp and an immense curiosity about the world of birds. He was an old-school naturalist, and in the days before binoculars and cameras, one studied wildlife by shooting it. Then you’d taxidermy it. No one really thought anything about it.

Scott gained his footing in the world by collecting birds, the intensity of his interests earning him entry to Cornell University, then to Harvard, where he contributed many specimens to the Museum of Comparative Zoology, which is still a thriving part of the university.

For a short while he worked as a taxidermist for the millinery trade, arranging birds in attractive poses that would later decorate women’s hats. He took a short gig acquiring birds for the new collection at Princeton University (then called the College of New Jersey), staying on and eventually rising to be the head of the ornithology department there.

Scott made his first collecting trip to Florida in 1875. There were not many roads at the time and he recalls riding to Silver Springs via a rickety stern-wheeler on the Ocklawaha River and having an edenic experience. He saw bird species he had never seen before wherever he looked – white ibis, anhingas, roseate spoonbills, Carolina parakeets (now extinct), etc. He wrote, “never had my wildest fancy painted, not only so many kinds of birds at one point, but such vast multitudes of representatives of the several kinds.”

When he made his second trip in 1879 the scene was vastly different – the populations of birds and other wildlife he’d marveled at along the river were essentially gone. “Such conditions had resulted from the almost universal practice of the (steamboat) passengers shooting at everything alive.”

The crew on the boat somehow believed it was the fault of the birds.

When Scott made it to the Maximo Rookery in St. Petersburg, the trip was somewhat redeemed.

“Conceive, if possible, this vast assembly of harmless, gentle, conspicuous, and beautiful birds during the breeding season,” he wrote. “It was a colony of birds that the eye could not take in at a single sweep. In the landscape the feathered population was the predominant feature.”

When he returned seven years later, the rookery was a barren landscape, all the birds gunned down and shipped north for the millinery trade. (Feathers at the time were more valuable per pound than gold.) Scott wrote a series of three articles describing the scenes in detached observational language in the ornithological journal The Auk, which sparked the first set of laws to protect birds, and also inspired the creation of the National Audubon Society.

He set out for Key West from the Gulf Coast in 1890 on a hired schooner. Along the way, near Cape Sable, he saw a flock of what he estimated to be 1,000 American flamingos, spreading out over a mile. No one has seen a flock that large in North America since.

He spent about three weeks in Key West, collecting specimens of mangrove cuckoo, black-whiskered vireo and great white heron. Then he headed out to the Tortugas, and back to the Gulf Coast.

Scott had actually met John Atkins previously in Punta Rassa, which is now a neighborhood of Fort Myers, sometime in the late 1880s.

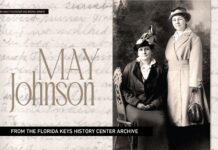

People steeped in Key West history may know of Atkins because of his career as the telegraph operator and chief engineer for Western Union. His biggest claim to fame in that realm occurred on Christmas Day 1900, when he made the first international telephone call to Cuba. It apparently consisted of Scott speaking, a lot of static, and then the operator on the other end of the line saying, “I don’t understand you.” But Western Union valued him enough to name a cable ship, the John W. Atkins, after him. That ship was the predecessor of the Schooner Western Union, Key West’s flagship that now sits decaying in a Stock Island boatyard.

There are actually multiple photos of John Atkins on the Florida Keys History Center’s Flickr page. The photo here is of him leaning against the Western Union cable hut in 1900. (Warning: Looking through the history center’s massive collection of historic Keys photos can result in the loss of multiple hours of work productivity.)

It’s unclear what kind of friendship Scott and Atkins had. Atkins goes unmentioned in Scott’s writing about Key West in his memoir, “The Story of a Bird Lover.” And I haven’t been able to find any additional correspondence. But in a paper about the avifauna of the Florida Keys published in The Auk, Atkins is Scott’s sole source, having procured and shipped the skins of almost all the species he wrote about, as well as providing all the information about their habits and habitat.

Scott is also his sole source in a more extensive paper about birds of the Gulf Coast, which included Key West, and contributed information about the behaviors of birds Scott saw and collected at the Dry Tortugas.

Scott, in his writings, mostly paraphrased Atkins, and the information always seems specific and precise. There are a few direct quotes with very specific details, like the one about the dove head, but it is hard to get a sense of Atkins’ voice. Atkins did write one article in The Auk, a note about a rare dove, the bare-eyed pigeon, that showed up in Key West. But other than that he seemed happy to have Scott take the limelight.

Scott did honor Atkins, though, by naming a subspecies of the white-breasted nuthatch after him.

“This name is given to record in a slight way my great appreciation of the careful work done by my friend Mr. John W. Atkins of Key West,” Scott wrote.

The subspecies was later lumped with two other subspecies.