By Alex Rickert, Jim McCarthy and Mandy Miles

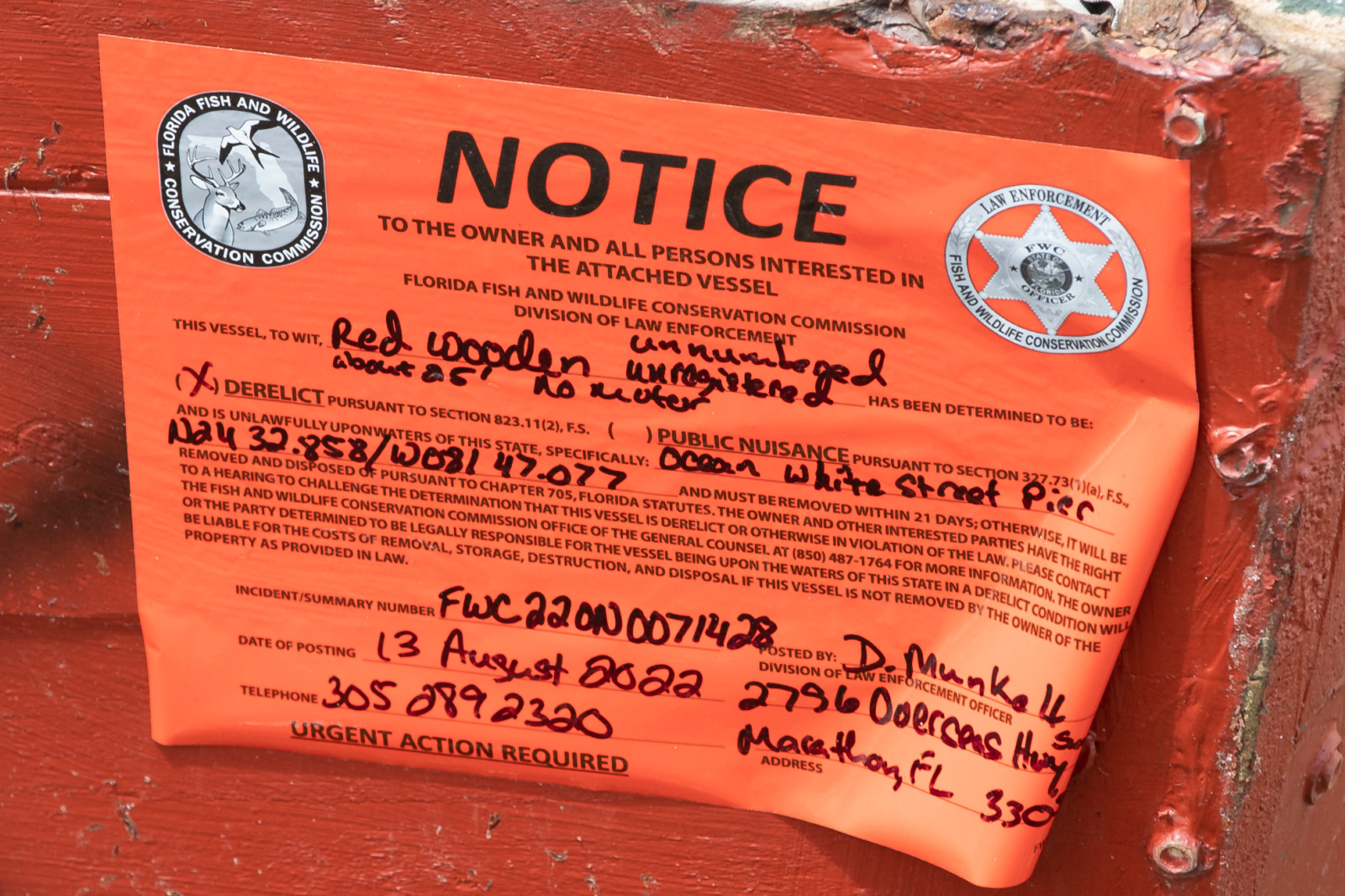

Migrant landings by Cubans and Haitians in the Florida Keys have become a near-daily headline. A growing collection of handmade vessels, known as “chugs,” wind up on Keys beaches and provide insight into the 90-mile voyage across the Florida Straits that an increasing number of people are willing to endure.

The relentless reports of migrant landings have led many in the island chain to wonder what’s happening to the new arrivals, what’s supposed to happen, who’s in charge and whether the former U.S. policy of “wet foot/dry foot,” which allowed Cubans who reached American soil to remain here, is truly a thing of the past.

One Lower Keys resident was “disgusted” by the action — or rather, inaction — of multiple government agencies on Sunday, Aug. 28, when he reported a vessel of 15 Cuban migrants, including children, that was taking on water about 10 miles south of American Shoal.

“I was out fishing, and looking for birds with my binoculars, when I saw an open vessel, no markings, with about 15 people on board, including children,” said the resident, who gave his name to the Keys Weekly, which confirmed his identification, but asked that his name not be used here due to his background in law enforcement. “I could see the vessel was taking on water and two people were using manual bilge pumps to pump it out. The people all had towels over their heads to shield them from the sun.”

The Keys resident first called 911, where dispatchers from the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office notified the U.S. Coast Guard, which handles migrants at sea. “I then called the Coast Guard directly, both on the phone and on the marine radio. I gave them the lat./long. coordinates of the vessel, its direction and speed of travel, including where they would likely land on Sugarloaf. Nothing. I was in sight of them for nearly two hours and no one responded. The Coast Guard never showed up. So I called FWC (Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission), thinking they’d for sure respond to a vessel taking on water with kids on board. Their dispatcher flat-out told me they weren’t going to respond. Then I called a number for Customs & Border Protection and couldn’t even get anyone on the phone.

“I have GoPro footage of me on the phone with these agencies, reporting the exact location and the fact that the vessel had children on board and was taking on water. That should have been enough right there. But nothing.

“This was a disgrace,” he said. “No one showed up. And who knows? These agencies don’t know for sure these are Cuban migrants. What if that’s an ISIS or some terrorist cell posing as migrants?

“If this didn’t happen to me on Sunday, I wouldn’t have believed it. And then, I hear a Coast Guard commander on the radio Monday morning talking about their big ‘Migrant Mission’ and stepped-up patrols. No way. They didn’t show up when they had all the information. No one knows what’s happening with these people.”

UNPRECEDENTED ILLEGAL CROSSINGS

Illegal crossings by both land and sea have surged in historic fashion over the past year. From the beginning of October 2021 through the end of August 2022, U.S. Coast Guard crews interdicted 7,173 Haitians and 4,822 Cubans while still at sea.

In the last 11 months, the number of Haitian migrants interdicted nearly doubled the number intercepted by the Coast Guard in the previous five years combined. Meanwhile, the number of Cuban migrants is at its highest since 2016, just prior to the expiration of wet foot/dry foot, when Coast Guard crews intercepted a total of 5,396 migrants.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection Commissioner (CBP) Chris Magnus visited South Florida and the Florida Keys last week amid the rising migrant landings. Speaking with Local 10, Magnus acknowledged that reforms are needed and that the immigration system is broken.

“No question about that. It’s a scenario where I wish we would see action from policy makers where reforms to the entire system give people legal pathways into this country.”

Magnus added that CBP is looking into bringing more resources to deal with migrant encounters. “We are really looking at that carefully in Washington,” he said.

Though the spike in ocean crossings to the Keys is significant, the numbers still pale in comparison to the number of migrants intercepted at the U.S.-Mexico border. According to a Washington Post report earlier this year, more than 32,000 Cubans were taken into custody along the border in March 2022 alone. At the time, Customs and Border Protection was on pace to arrest more than 155,000 Cubans during the 2022 fiscal year. A Wall Street Journal report published in April 2022 indicated that the U.S. had made more than a million arrests at the border since October, indicating “the fastest pace of illegal border crossings in at least the last two decades.”

POLICY CHANGE UPS ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION

While migrants seeking asylum formerly crossed into the U.S. via legal avenues, the cessation of former protocols has seen migrants attempt increasingly risky voyages to reach the States. Under wet foot/dry foot, migrants who reached U.S. soil could obtain “parole” to enter the country legally. Thanks to the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966, Cuban migrants seeking asylum as political refugees from the Castro regime could shift to legal permanent residence after one year. According to a Customs and Border Protection Inspector’s Field Manual, migrants who cleared a background check could be issued a parole document directly at their point of entry, as long as they “(did) not pose a criminal or terrorist threat.”

Following the devastating 2010 earthquake in Haiti, migrants from the island nation were granted a similar humanitarian parole, and removals of Haitians without criminal records were suspended.

However, on Sept. 22, 2016, the Department of Homeland Security changed its policy and resorted to deporting Haitians, detaining migrants at border crossing points and only granting asylum if they could show a credible fear of persecution. Four months later, wet foot/dry foot was rescinded, forcing Cuban migrants to undergo the same process.

Since 2016, the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border has once again earned a national spotlight as CBP ports of entry have taken measures to cap the number of migrants allowed to enter the country and seek asylum. The 2019 Migrant Protection Protocols, informally known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy, found growing populations of migrants waiting in dangerous border cities and camps to present their asylum cases. With crossings through Mexico becoming less viable, more and more people are taking their chances at sea.

Haitian voyages to the U.S. rose following the assassination of then president Jovenel Moïse at his home in Port-au-Prince on July 7, 2021. With warring gangs and bloodshed on Haiti’s streets also came an economic crisis.

In recent times, thousands of Haitians have taken to the streets to protest rampant crime among gangs, which have left hundreds and even thousands dead, and soaring consumer prices. Jean Baden Dubois, Haiti’s central bank governor, told Reuters that inflation reached 29% in June 2022 — a 10-year high. Many have struggled to find necessities such as gas. And that’s left many unable to work.

In Cuba, an economic crisis not seen in 30 years and political repression are among the reasons for increased voyages to the U.S. among Cuban migrants. Jorge Duany, head of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University, told the Wall Street Journal that the exodus “reflects desperation, the lack of hope, and the lack of future people on the island feel.”

In early August, a fire ravaged 40% of fuel storage at the port city of Matanzas. That led to an increase in power outages, which had already been lasting 20 hours a day in various places.

WHEN MIGRANTS ARE CAUGHT ON THE WATER

If migrants are successfully interdicted on the water, they have a much simpler path to repatriation, one that will never include touching U.S. soil and officially seeking asylum. According to Coast Guard policies, they are transferred from their vessel to a Coast Guard cutter, where they receive basic medical attention, fresh clothing, food and water. Coast Guard crew members conduct background checks on those aboard before returning them to their home countries.

WHEN MIGRANTS TOUCH LAND

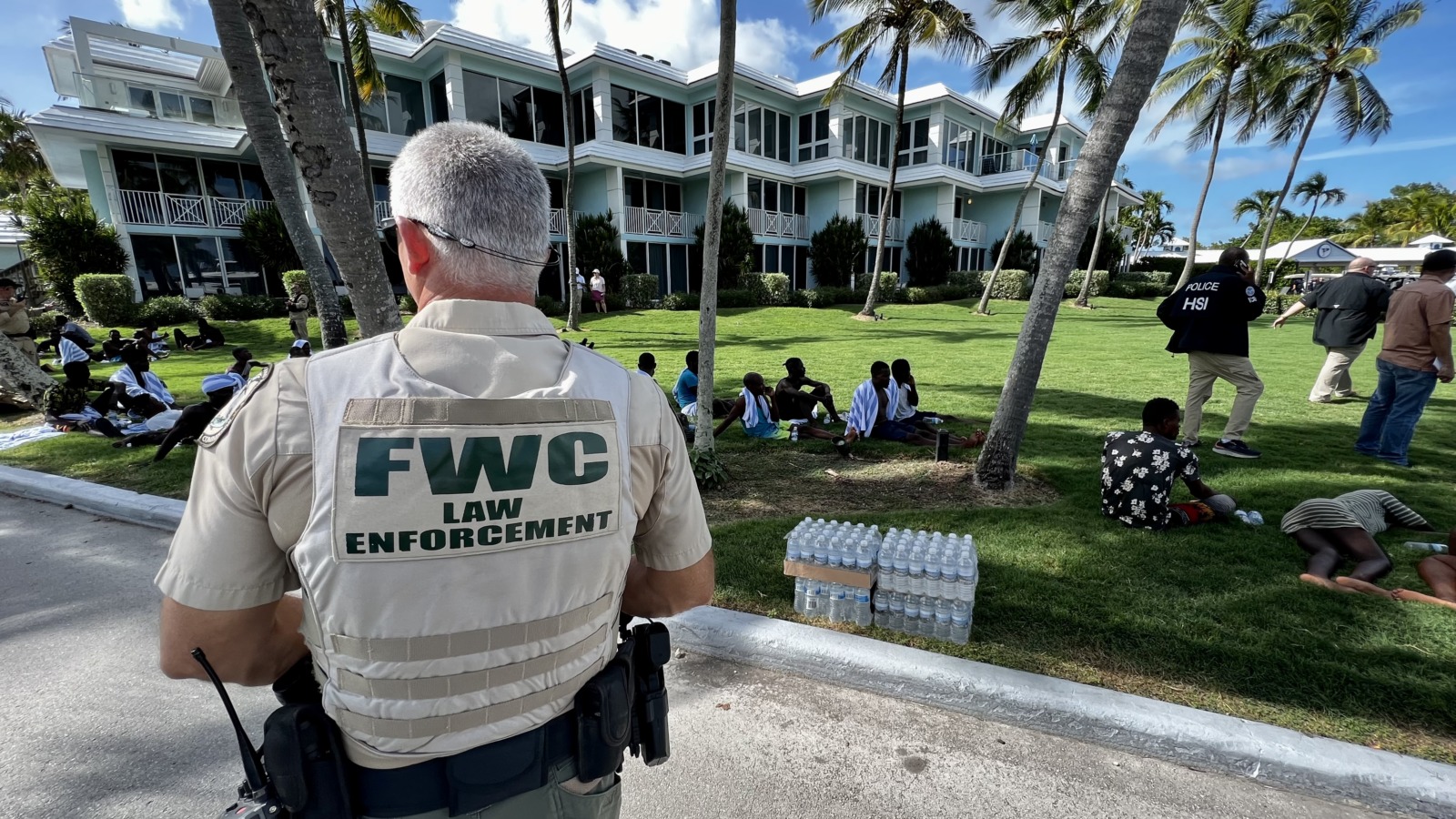

Though multiple agencies including the Coast Guard, FWC Law Enforcement and the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office may assist with individual incidents, migrants who successfully reach land in the Keys or elsewhere are detained by CBP agents and processed for removal proceedings. What that process looks like ultimately depends on each individual situation and the agency’s ability to manage the number of migrants at that point in time. Migrants may request an asylum hearing before an immigration judge, where they may attempt to prove a credible fear of persecution if they are returned to their country of origin. Some, but not all, may receive a preliminary interview with CBP before officially moving toward this hearing.

Even to those most familiar with the situation, the road map for migrants is unclear at best. But in the end, those who make it to land today do appear to have a good chance of remaining in the U.S.

According to a source familiar with resources provided to migrants, if they have family members waiting to receive them, “their outcomes seem to be better off.” Single migrant males may also pair with pregnant females extremely close to giving birth, giving the appearance of a family while providing security and protection to women who may otherwise be targeted by violence. Individuals who are able to open official immigration cases before beginning their voyages also typically fare better – or at least experience an expedited process – upon reaching the States.

“Once you touch American territory you have the right to go before an immigration judge and seek asylum,” Miami-based immigration lawyer Willy Allen told CBS Miami in a July 2022 report. “They have a shot to stay here,” he confirmed, adding that four of the last five undetected Cuban migrants who applied through his office were granted asylum.

However, backlogs in immigration courts are resulting in incredibly long wait times. According to an immigration case tracker published by Syracuse University, pending immigration cases in Miami courts were experiencing wait times of 550 days or more.

“I thought it was something wrong with the system,” said one individual attempting to schedule an immigration hearing for a family. “I just kept going along the calendar. By the time I hit 2032, I just gave up.”

With capacities limited for detaining migrants, many may be paroled while waiting for a hearing. Official documents may not even reflect the reality of individual situations.

“There is a family who arrived here by Smathers Beach in Key West,” the same source told Keys Weekly. “It just sticks in my mind because I know firsthand that they had family to receive them. They stayed in Key West, but the paperwork shows that they were in a detention facility in Miami and then they were released to this family. But that wasn’t the case.”

Further complicating matters are the efforts to catch and properly prosecute those conducting human smuggling operations. In order to reach a conviction at the end of a prolonged federal investigation, prosecutors need to keep a few witnesses around.

VOYAGE DANGERS

Taking to the seas in a rustic vessel poses many dangers for migrants, especially during hurricane season when the waters can be unpredictable and deadly if unprepared. What makes the journey even more dangerous is the lack of safety gear or lifesaving equipment by migrants as they make the voyage. Lt. Paul Puddington, of Coast Guard’s Seventh District, said they’re maintaining a heavy maritime presence to detect and interdict anyone attempting to illegally migrate by sea in the Florida Straits and Caribbean region.

“These voyages are not only illegal, but also incredibly dangerous. No one should risk their lives on unsafe rustic vessels in unpredictable seas.”

Voyages also pose a risk to the community. On Aug. 8, Marathon residents living in the area of 79th Street Ocean in Marathon witnessed more than 100 Haitian migrants running through their community after their boat ran aground offshore. A total of 109 migrants jumped in the water and swam to land before they were eventually apprehended by CBP agents.

Investigation by CBP found that one of the migrants was a sex offender who was previously convicted of fondling a child and kidnapping. The man was arrested.

U.S. Rep. Carlos Gimenez told the Keys Weekly that journeys by land through the southern border or by sea through South Florida often result in kidnapping, human and sexual trafficking, and in some cases death.

“All the focus and media attention has been on the southern border, but this is truly a two-front battle,” he said. “Our maritime border, as evidenced by the constant landings in the Florida Keys and through South Florida, need just as much attention if we’re going to put an end to this humanitarian crisis.”