By Scott Atwell

When Bruce Sutter died last week after a brief bout with cancer, he was universally eulogized in news reports as a pitcher whose baseball career was resurrected by his adoption of a little- known pitch called the split-finger fastball. Even lesser known is that Sutter perfected the pitch as a minor leaguer in Key West.

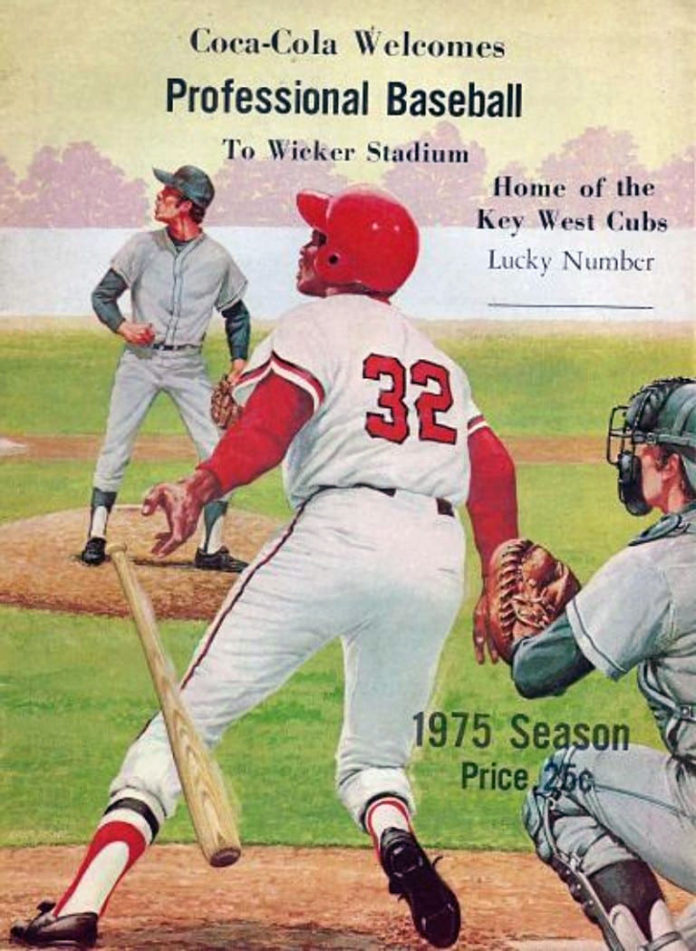

The Southernmost City had a nascent history as a professional sports town, beginning with a single season in 1952 but, more broadly, in 1969 as a Florida State League farm team of the San Diego Padres, and lasting until 1975 as the Class-A affiliate of the Chicago Cubs. In between, the local team suited up as the Sun Caps in 1971, and then as the Conchs from 1972-74, playing home games at long-lost Wickers Field on Kennedy Drive. The Sun Caps were an unaffiliated, co-op team with a roster stocked with misfits from other programs. The Conchs were Cubs hopefuls.

Key West was excited by the novelty of a pro team, attracting more than 40,000 spectators in each of the first three seasons. But after back-to-back last-place finishes in 1971 and 1972, the turnstiles dwindled by half.

Dr. Julio dePoo, one of the team’s co-owners, would sit in his wheelchair at the third base corner of the grandstand, guarding a box of baseballs until the umpire signaled for replacements. Once, when legendary Ernie Banks was visiting Key West as a roving coach in the Cubs minor league system, I retrieved a foul ball and asked him to sign it. Believing the baseball was still playable, Mr. Cub, as he was known, asked me to return it to Dr. dePoo, and promised to sign another one after the game. Later, I waited underneath the grandstand in a cramped office, but went home empty-handed. That moment forever soured me on Mr. Cub, though it was, l’m sure, an unfair judgment.

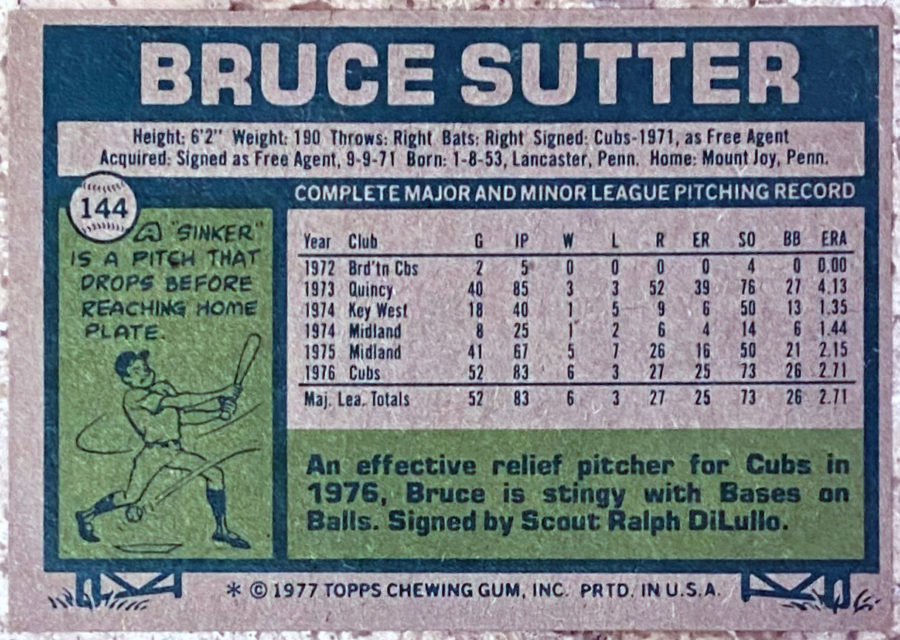

Sutter’s 1974 Key West team also finished in last place, but minor league baseball is less about standings and more about player development, and Sutter was about to develop into a big leaguer. Soon after turning pro he struggled with arm trouble and used his own signing bonus to pay for a nerve operation, keeping it secret from the Cubs. But the surgery cost Sutter pitch velocity and, at age 21, he was on the verge of getting released, when a Cubs assistant approached him at spring training in 1974 and offered to teach him a new pitch. Sutter’s long fingers provided a perfect launch pad for the split-finger, and when camp broke, he was dispatched to Key West with instructions to work out the kinks.

Sutter appeared in 18 games for the Conchs that season, all but one in relief, logging 50 strikeouts in 40 innings on the mound. In Key West, armed with the split-finger, his ERA dropped from above 4 to 1.35. The Cubs promoted Sutter to double-A late in the season, and by 1976 he was pitching at Wrigley Field, the first of a dozen seasons as the most dominant reliever in the big leagues, where he logged exactly 300 career saves with three different clubs.

“I tried to bunt on him because I can’t hit him,” Reds catcher Johnny Bench told the L.A. Times in 1977. “He’s the best.” In 2006, Sutter was anointed as such, elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame with the distinction of being the first inductee to never start a game in the major leagues.

No doubt, Sutter is the most successful player who ever suited up in the home clubhouse at Wickers Field, but as many as 26 Key West players eventually made it to the big leagues, according to Baseball-Reference.com. Vic Albury pitched for the ’69 Padres farm club before breaking into the bigs with the Minnesota Twins. Two years after managing that Key West Padres team, Don Zimmer was summoned to the majors, where he skippered for 14 seasons. Native Conch Rich Garcia cut his teeth as an umpire in the Florida State League in preparation for a 25-year major league career. And one summer during college, Richie Bancells manned the Wickers Field press box as scorer and announcer, before working almost 40 years as athletic trainer for the Baltimore Orioles.

The isolation of the Keys made pro baseball a difficult business proposition. Players were known to sleep in the clubhouse because affordable housing was scarce. The team’s trainer lived in a trailer beyond the outfield fence. Although the 1975 Key West Cubs won 65 games and earned a spot in the Florida State League playoffs, the parent club relocated their Class-A team to Pompano Beach the next season.

It was a sad reality for me, a young teenager who had spent a couple summers volunteering as batboy for visiting teams. A lot of those visiting players made it big, and decades later I ran into Mike Heath, who visited Key West as a Fort Lauderdale Yankee en route to a 14-year career as a big-league catcher. When I mentioned picking up his bats, the first thing that crossed his mind about Key West was pre-game meals. “We ate at a drugstore,” he laughed. I knew immediately, of course, he was talking about the old Dennis Pharmacy at Simonton and United streets, a popular dining spot for locals.

One of my favorite visiting teams was the West Palm Beach Expos, who had a friendly manager named Gordon MacKenzie. Once, during pregame warmups, Mac was sitting on the bench watching a low-flying airplane approach the stadium with smoke trailing from behind. He leapt from the bench and started screaming about a crash. I had to explain our mosquito control planes to him. Later, while covering spring training during my sports reporting days, I ran into Mac when he was with the Detroit Tigers. He walked me around the locker room, introducing me as his minor league batboy. Gordon died in 2014 and now Bruce Sutter is gone at age 69, and I am filled with nostalgia as I type. Don’t get me wrong, I love the George Mira football complex, where Wickers Field once stood, but every time I pass that intersection of 14th Street and Duck Avenue, it’s the Wickers Field grandstand that I see. And it’s a window to my childhood.