I was invited to speak at the 2024 Ernest Hemingway Seminar at the Community Library in Ketchum, Idaho. Hemingway’s last home was in Ketchum, and it was there where things ended. When I was in graduate school, the father of one of my classmates performed the autopsy on the writer.

At the inaugural 2009 seminar, that old classmate, David Earle, was featured as a speaker. Key West’s own Arlo Haskell, author and executive director of the Key West Literary Seminar, presented at the 2017 Hemingway Seminar.

The reason their committee reached out to ask if I was interested in speaking at the three-day event had nothing to do with Hemingway. In September, I’ll be flying out to give the seminar’s closing talk on piracy and smuggling in the Florida Keys. I could not be more honored or more stoked.

You can’t talk about piracy in these waters without talking about the island chain’s legendary pirate, Black Caesar. While exploring the pirate’s storied history for Volume 2 of my “Florida Keys History with Brad Bertelli” book series, I was able to include a connection to Hemingway – sort of.

The earliest literary account of Black Caesar that I have uncovered is a story called “Jack Weatherwax: The Wrecker of Caesar’s Creek, A Tale Of The Florida Reef in the Olden Time,” which appeared in The Jackson (Ohio) Standard on April 22, 1858. The story describes the creek flowing between two of the Northern Keys above Key Largo, Old Rhodes and Elliott Keys: “Black Caesar’s Creek because it was formerly the hiding place and rendezvous of a noted pirate known as Black Caesar, who was destroyed, and his gang broken up, by Commodore Porter’s expedition, in 1822 or 3 — perhaps by the same gallant ‘Old Plug,’ of whom I spoke in the Mercury not long since. It is a dark and crooked lane of water, leading to the inner bay, shaded by shelter on either side by high mangroves, and afforded an excellent hiding place for the pirates, who could suddenly dart out upon the merchant vessels passing up or down the Gulf Stream. Ah, were but all the records of the deeds done by those who once lurked there written, what a thrilling book of horrors that would make! One’s soul shudders to think of the murderous acts performed by the black-hearted pirates, whose motto was ‘Dead men tell no tales,’ and who only spared young and beautiful maidens, who fell into their hands, for sufferings worse a thousand times than death!”

Ned Buntline, a contemporary of Mark Twain, wrote the story. Like the name Mark Twain, Buntline was a nom de plume. His real name was Edward Zane Carroll Judson. His connection to the Keys comes through his service as a midshipman with the Navy during the second escalation of the Seminole War (1835-1842). Occasionally, he was stationed at Indian Key. Though he arrived in the Keys nearly 100 years before Hemingway, he shared traits with him, including the love of a good fight, good women and writing.

You cannot work in the realm of Keys history without the subject of Hemingway eventually entering the conversation. Because I’ll be speaking at a Hemingway seminar, I’ll share an anecdote or two that I’ve picked up. For instance, when I was hired to curate Islamorada’s Keys History & Discovery Center in 2013, one of my first assignments was to fly to Tallahassee and interview the 101-year-old Wilbur Jones. At the time, he was the oldest living survivor of the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane.

Jones worked as a safety officer during building of automobile bridges to eliminate the need for car ferries bridging the 40-mile gap in the first version of the Overseas Highway. The workers, many of them World War I veterans, were housed in three work camps, one on Windley Key and two on Lower Matecumbe Key. One of Jones’ jobs was to pick up nails and other potentially hazardous objects so no one stepped on them.

In our interview, he also said that every Friday, one of his jobs was to go to each of the work camps and offer a one-dollar advance on their pay. Jones said they rarely took the dollar and worked to send the money home to their families. At one point, toward the end of the interview, Jones asked, “Who was that writer in Key West who wrote all those things after the hurricane?”

“Hemingway?”

“Yes,” he said. “Hemingway.”

Hemingway wrote scathing critiques of the handling of the evacuation of the veterans in the work camps ahead of the killer Labor Day Hurricane. More than 250 veterans died in the storm because the relief train sent to evacuate them arrived too late. Jones raised his fist in the air and shook it a little. “He made me so angry. I was in the office when the calls for the rescue train were made.”

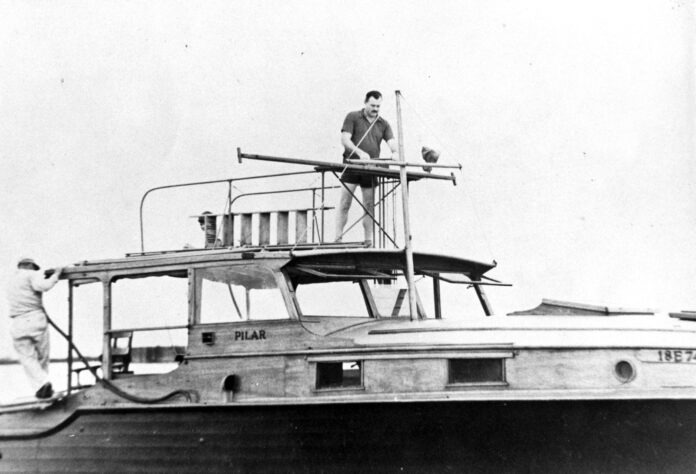

I have not listened to the interview in a decade, and I’ll have to revisit it and take a few notes before September because he was there when Hemingway loaded up the Pilar with supplies and motored up to the Matecumbe Keys to help. I’ll also have to do a little shopping, as my wardrobe is ideal for September in the Florida Keys. I have been told that September in Idaho will require something more than shorts and Kino sandals.