“You probably have heard enough about hurricanes,” but on Monday, Mote Marine’s Dr. David Vaughn told the volunteers of Save-a-Turtle what is happening underwater. “You can’t see it from the side of the road,” he said.

The visibility was horrendous for weeks after the storm, making it difficult even to survey the damage. Hurricane Irma’s wake left the waters surrounding the Keys a milky white, which between the cloudy water and the sediment that sandblasted the reef, left serious damage.

On the reef

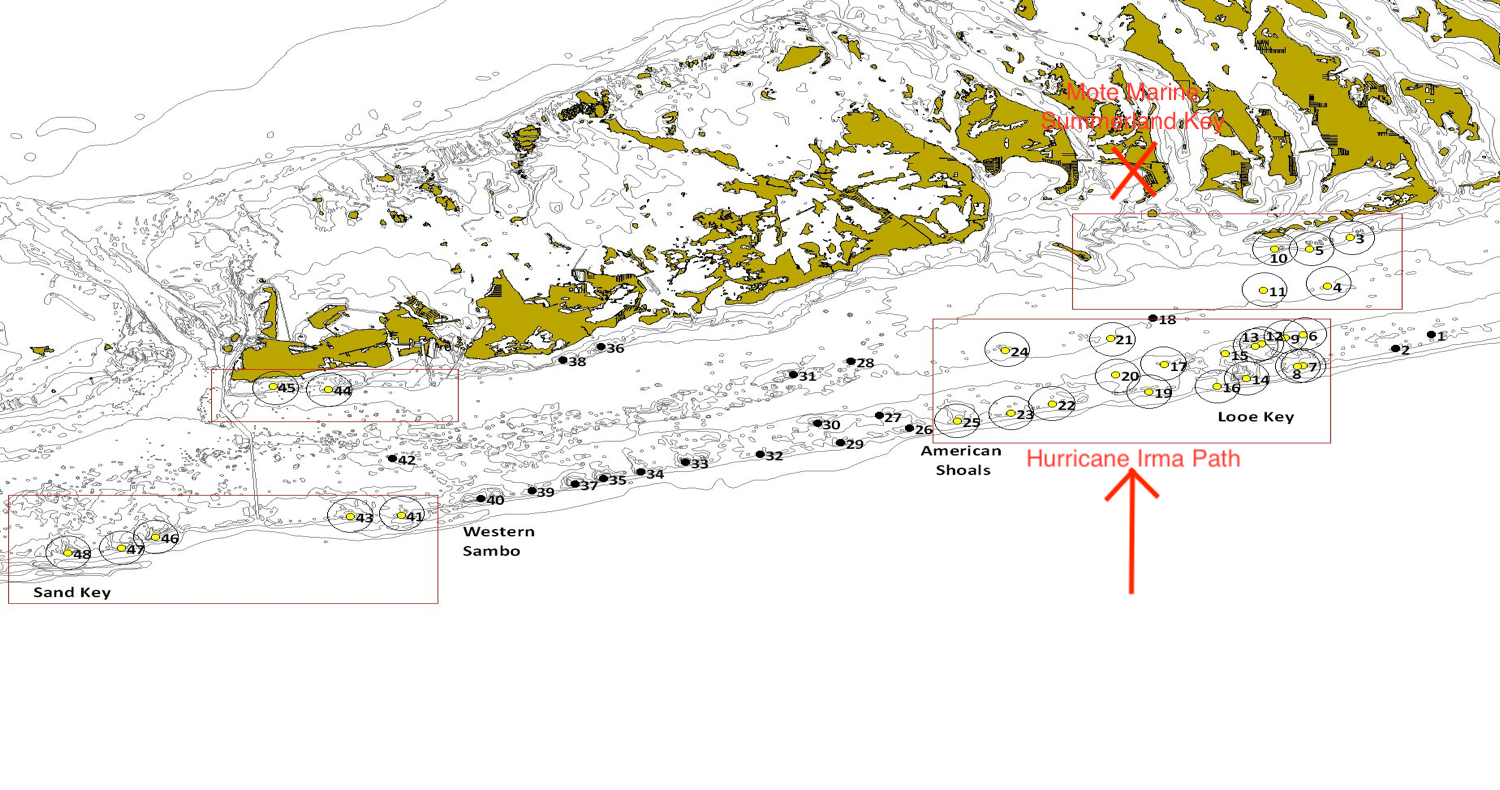

Three things played a role in the health of local corals during Hurricane Irma — the distance from the eye of the storm, the distance from the outer edge of the reef, and the size of the coral.

In the transplant areas, like American Shoal, before and after pictures were compared. The before picture: a group of five corals with an aluminum tag for each cluster being held to the hard bottom by a cast iron nail. Around the thriving area, sea fans swayed in the currents and algae had started to grow on the sea floor. After the storm, the nails were the only thing left.

“The distance from the storm made a big difference,” said Vaughn, who pointed out that many of the coral transplant areas were in Irma’s direct path.

What also made a big difference was whether the plantings were on the outer barrier reef versus the inshore reefs.

“Life in the Florida Keys would not be possible without the reef,” he said, explaining how the outer reef broke up the 30-foot waves, the inner reefs broke up the 15-foot waves, and the houses along the shoreline took the surge and 8-foot waves. “There is not one house on these islands that could take 30-foot waves.”

Off Cook Island, the massive corals did fine, although they are still wrapped in a lot of debris, lines and traps.

Moving further away from the eye, on Sand Key off Key West were two-year post plantings that held better than the American Shoal plantings. The 25-mile difference still wiped the algae off the corals, but the main parts of the tissue were intact. “The good news is we can put them back,” he said. “This shows us one thing: size matters, not age.”

Of the 12,000 corals planted on the snorkel trail off Ft. Zachary Taylor, only one was missing from the storm.

Sherri Crilly, vice president of Save-a-Turtle, mentioned Looe Key, “it looked better three weeks after the storm than it does now; every time I go out there it looks worse.” Mote planted 5,000 corals inside the special protected area. Vaughn explained how the sediment is smothering the corals out there, but slowly the reef will come back to all of its glory. “The soft corals are already coming back,” said Crilly. “And the sea life – including the goliath groupers – are already thriving again.”

Of the 105 coral trees planted around Looe Key — each with 120 corals dangling from it — only five survived Hurricane Irma. One tree was found off Cape Coral, Florida. Vaughn said the coral count should be back up to 7,000 this summer.

Inside the Lab

Hurricane Hugo destroyed eight years of oyster research in North Carolina and Dr. Michael Crosby at Mote Marine said if he ever had the chance to build something that could withstand a Category 5 storm, he would. Mote Marine christened the new building last year, just in time. More than 14,000 corals moved inside to the wet labs were saved and it’s a good thing, since the direct hit of Irma brought 4.5 feet of storm surge and high winds. “We were able to save 85 percent of the outside nursery corals,” said Vaughn.

During the storm, Vaughn and other employees who stayed behind were throwing outside corals into the empty shark tanks to try and save them. It worked. Since the storm, the 38 tanks, known as raceways, have been rebuilt.

There is hope

Hurricane Wilma in 2005 completely wiped out Cancun’s reef by Isla Mujeres, when Vaughn was sent to help with fragmentation. Last month, he was invited back, not to help with more fragmentation, but to see what he had rebuilt.

Starting with tops of Coke bottles cut in half with the coral cemented in the top of it, today the rebuilt reef is flourishing with fish, hard corals and natural soft corals. “This is what we will expect three to five years from now,” he said regarding local reefs.

“He is literally saving the human race because he is saving the reef,” Harry Appel, president of Save-a-Turtle, about Mote Marine’s Dr. David Vaughn

A number of countries around the world are learning how to do this. “We can’t afford to lose the coral habitat,” he said. “It won’t matter 100 years from now if all the species are gone if we rebuild the reefs; we have to save the habitat now.”

In the Keys, the reef supports 70,000 jobs and $1 billion in local industries.

“We learned about bleaching in the ’70s,” said Vaughn. “We thought that was a once-in-a-century event and lost about 20 percent of corals.” Then, in the ’80s, there were back-to-back years of bleaching, where 5 to 10 percent of the corals were lost.

“We have had bleaching 12 out of the last 18 years,” he said. “There is some natural resistance out there; we lost the susceptible ones.”

Mote has been working with multiple genotypes that show natural resiliency. “We want our corals to win the Summer Olympics in 2050,” he said. “But, right now, it’s a BandAid, it’s not solving the underlying problem that is causing the bleaching.”

Twenty years ago, a good reef was considered to be at 50 percent coverage; today the average is around 6 to 7 percent.

Mote Marine on Summerland Key offers tours on Tuesdays from 10 to 11 a.m. and on Fridays from 3 to 4 p.m. No reservations are needed.