The sculptor John Martini works out of a large blue building on Emma Street. You’ve seen it — if not in real life, then as the backdrop of a wedding photo or someone’s Key West adventure selfie. At first you notice the blue facade, a deep and resonant color, reminiscent of the way the water looks when you get out past the reef and the bottom drops away. Then you notice the green doors, which look a little more nearshore, then the door handles, two heads in profile, facing each other, cut rough out of steel in Martini’s iconic style. A small sign in one of the windows says Terminal Art Works.

The building was once the Lincoln Theater, the Black theater in the time of segregation. (The movie “Caribe Gold,” filmed in Key West in the 1950s with an all-black cast, simultaneously premiered there and at the Strand on Duval Street.) After that it was a flophouse, possibly a brothel, and then the Dr. Martin Luther King Memorial Church. It had been abandoned for a number of years when Martini bought it in the early 1980s. There were no windows then, and Martini remembers stepping into the darkness and seeing the place in the beam of a flashlight.

“It was like looking into the universe,” he said.

“It was like looking into the universe,” he said.

Mostly he recalls it being empty, other than an old lamp and a cement baptismal font filled with dozens and dozens of high-heeled shoes.

When I stopped by the other day, it felt more bright, industrial and industrious, though granted, this was in the run-up to his opening March 26 at JAG Gallery, 1075 Duval St. Deadline pressure is a motivating factor in many artists’ lives.

Lights blazed from the ceiling and giant doors on the sides of the building were open to let the air move through.

Being an old theater, the floor drops down at an angle, and walking through it feels something like immersing yourself in the steel menagerie of Martini’s psyche, all carved with an acetylene torch. Completed works are in the front, large steel figures — animal, human and other — arranged like trees in a forest to save space.

Further on is where the new work takes shape, sawhorses and tables covered with parts of larger assemblages, winches, pulleys, chains, welding torches, grinders, handtrucks, stools, small piles of scrap and several rows of painted metal plates – 5 feet by 8 feet, ¾-inch thick – waiting to be cut.

Martini came to Key West in 1977. He’d grown up in New Jersey, worked as a community organizer for several years in St. Louis, then moved to Atlanta, where he began to make jewelry, at first as a hobby, then professionally. While he was there he had his first sculpture commission, an award he won by applying with drawings. He had to go to auto body welding school to figure out how to actually make the thing.

Martini came to Key West in 1977. He’d grown up in New Jersey, worked as a community organizer for several years in St. Louis, then moved to Atlanta, where he began to make jewelry, at first as a hobby, then professionally. While he was there he had his first sculpture commission, an award he won by applying with drawings. He had to go to auto body welding school to figure out how to actually make the thing.

“The sculpture in Atlanta was completely abstract. It bore no relationship to what I eventually started doing. Other than the fact that it was steel,” said Martini.

He was in his studio in Atlanta one day when the pipes froze. He brought a bunch of electric heaters to warm them and then the pipes burst. Standing amongst the icy cold water and the extension cords, he said he had a vision of palm trees, soon finding himself on a plane to Miami and then a Greyhound down U.S. 1. When he got to Key West the driver recommended the Southern Cross Hotel, where he got a room.

“About 4 o’clock that afternoon I went out and walked around Key West. I crossed the street when I got to the Green Parrot because it looked pretty shady,” he said. (His sculpture now hangs on the wall.)

“All night long I walked around Key West. I saw that stone church and it was empty and I thought, wow, this place is great,” he said.

“All night long I walked around Key West. I saw that stone church and it was empty and I thought, wow, this place is great,” he said.

He went back to Atlanta and he and his then wife/now neighbor Darene packed up a U-Haul and drove south. The plan was to stay for three months.

Eventually he bought property, renovated a few houses. He worked as a cab driver, bussed tables at Logan’s Lobster house, got a captain’s license, ran a sailing school. He is the only artist I know who has graduated from shrimp boat deck handling school, though he can’t immediately lay his hands on the diploma.

He opened Lucky Street Gallery a year or two before he bought the studio on Emma Street. He showed the work of your more avant-garde local artists, some folks from out of town, and a lot of outsider artists from the south. He found himself greatly influenced by the work of a number of Haitian artists. (JAG Gallery, owned and managed by Letty Nowak, is something of the spiritual successor to Lucky Street, which closed after its last iteration and ownership change a little under two years ago.)

Martini’s first studio was at Truman Annex, recently abandoned by the Navy.

Martini’s first studio was at Truman Annex, recently abandoned by the Navy.

“There were still bowling pins around. The plates were still on the table. It was like a neutron bomb went off. So there was lots of shit and nobody watching. So you could go around and scrounge and cut up old tanks and stuff. Which I did,” he said.

It started him down the artistic path he’s been on for the last 40-plus years. (Some of his adventures there are chronicled in Rita Troxel’s recent compendium of stories from that era, “Home at the End of the World.”)

He started cutting shapes out of the steel, some of it 100 years old, covered in layers and layers of paint. The early pieces were angular, looking a little new wave, but straight lines gave way to curves, and soon it evolved into visual vocabulary that is the basis of his work today, work defined by its freeness and its fluidity, a style that conveys a lightness of movement contrary to the sheer physical weight of it all.

Influenced by the experiments in automatic writing by artists such as André Breton, he tried to approach the steel blank, seeing the shapes in it and drawing spontaneously, outlining in chalk before firing up the torch. The edges of the work came out raw and exposed, the paint thickening as you move toward the interior like a rising tide. The rust, when it happens, has always been part of the plan.

In recent years his work has become more layered and mechanically complex. Instead of carving the shapes and silhouettes from a single piece of metal, he carves out multiple shapes and bolts them together in a more multidimensional effect. He works them out in a sketchbook first.

“I don’t really enter my sketchbooks with an idea. It’s a process of accumulation. So eventually I’ll come to a place where essentially the piece is done in the sketchbooks. Then I’ll do very simple measurements. Ratios. It’s not all perfectly engineered. I scale it up in the roughest way,” he said.

No longer able to scrounge pipes and I-beams and other old steel, Martini now has plates shipped in. He paints them with multiple coats before cutting into them, keeping some the same sedimentary color effect.

“The pieces have become more engineered now, out of necessity. It was just an evolution. I’m not sure how I got to that, but it just allows more freedom. Of expression. Of creating the imagery,” he said.

“The pieces have become more engineered now, out of necessity. It was just an evolution. I’m not sure how I got to that, but it just allows more freedom. Of expression. Of creating the imagery,” he said.

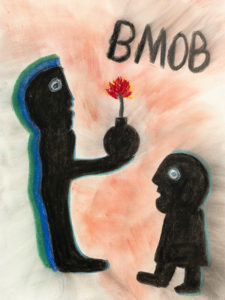

He also keeps things spontaneous by making monoprints and, over the last year, making drawings, several of which will be included in the JAG Gallery show. (Many of the creatures within have taken on virus-like characteristics in COVID times.)

Martini wants people to bring their own interpretation to his work, though the term whimsical, which sometimes gets applied, can raise his hackles.

“Most of my work, I look at it as very dark, though nobody else generally sees it that way,” he said.

Though most of the work comes from his self-consciousness, Martini says the work would no doubt not be the same if he hadn’t taken that Greyhound ride down U.S. 1 way back when.

“Key West has been an incredible gift,” he said. “Key West has given me so much.”