Jerry Greenberg can often be found examining laminated photographs of Key Largo reefs long gone. Those who don’t know would never guess that the 93-year-old is the guy when you’re talking about Keys reefs, diving and underwater photography.

Greenberg, a native of Chicago, was born in 1927, and his parents bought a winter home in Miami Beach in 1937.

“I grew up here swimming and being out in the water here,” he said.

At Miami’s Beach High, he took up spearfishing and photography. He became a photojournalist, and since the 1950s, Greenberg has photographed the Keys’ reefs and advocated for their protection. He shared some of the history he’s witnessed.

“Do you know how they chose the site for the statue, the Christ (of the Abyss)?” Greenberg asked.

He talks about Edigi Cressi, the Italian dive equipment manufacturer, “being the good Catholic that he was.” Cressi made three Christ statues and gave the last to the Underwater Society of America, which didn’t know where to put it.

“They asked my high school friends, the ‘Dead-end Kids,’ the spearfishing guys, and they showed them where to put it — in a sandy patch near a huge brain coral on Key Largo Dry Rocks, which was the most vibrant reef back then,” Greenberg said.

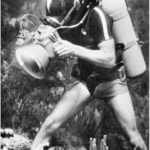

He remembered when the Benwood wreck hadn’t been picked apart by metal salvagers, and how neoprene was invented as a World War II effort to lessen U.S. dependence on Japanese rubber. He also used the first aqualung that came into this country from France.

“I knew a guy at a fraternity, and he bought the first aqualung sold at a Miami gun shop,” he said. “There were no compressors back then, so bottles had to be filled at fire stations.”

Greenberg first took pictures underwater by shooting through a glass-bottom bucket as his window to the underwater world. Eventually, he made all his own underwater housings for cameras and even manufactured housings, since what he needed didn’t exist.

“I had the best equipment in the world, and I had that lead for many years,” he said. “I had big banana boxes that had my camera housings in — one big box with three cameras in it, and I had two boxes. That’s how I did all my work.”

Lad Akins, a Keys dive legend in his own right and Greenberg’s long-time friend, recalled the same scene on Key Largo’s reefs.

“Back then, Jerry was a striking figure going out in his Boston Whaler all alone,” Akins said. “At the reef, he had a huge innertube that he kept all his cameras in ‘cause back then it was film, limited to 36 exposures. So, he brought a bunch.”

Laughing, Akins added, “Sometimes he could be a little challenging, like if you pulled up on a reef he was on and he was busy doing his photography. He’s salty, crusty and he takes his work seriously. I always respected him.”

Stephen Frink, a prolific underwater photographer and friend of Greenberg’s since the 1970s, said, “Jerry’s like me. He wouldn’t be a diver if not for being an underwater photographer. People starting out today will never understand how many things he invented because he had to. No one else was doing what he was doing in the late ’50s, early ’60s.”

“Jerry’s got this visual history of what the Keys were like, like South Carysfort when it was really beautiful,” Frink continued. “I don’t know anyone else with the wide-angle scenics from 1960-1975. There’s a visual history that resides in his archives, and he’s probably the only person with it. That profound legacy cannot be understated.”

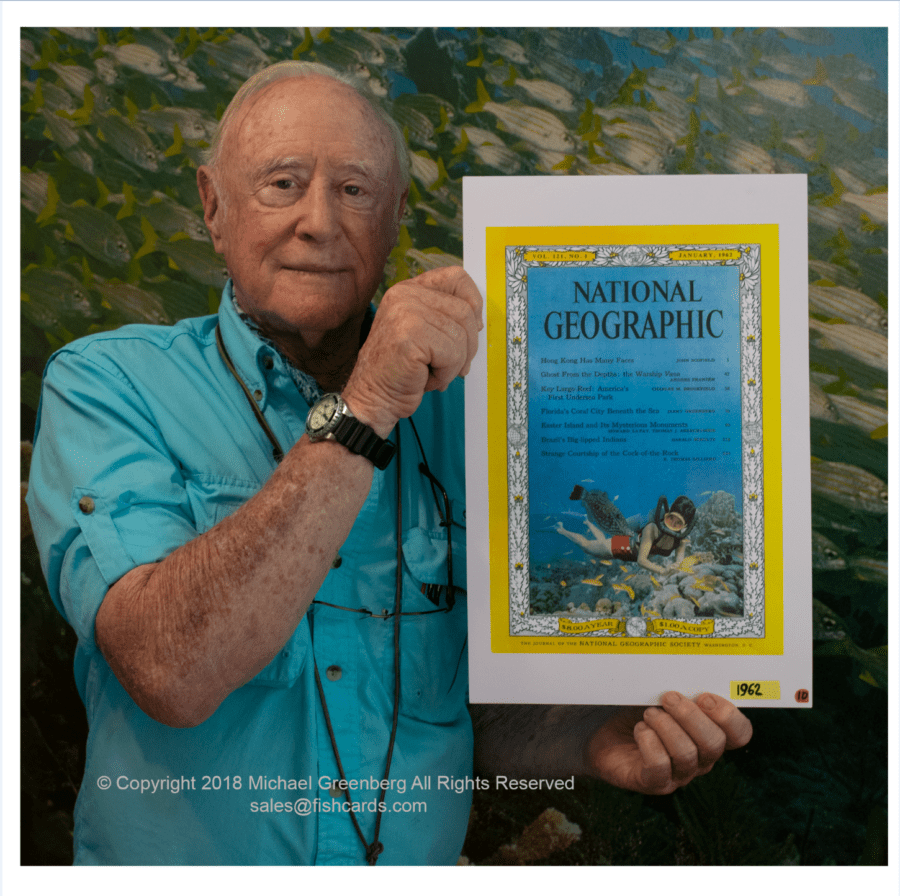

In 1962, National Geographic reached out. Greenberg photographed a young diver over a vibrant coral reef in an early aqualung prototype, an image that would captivate millions as the magazine’s first color underwater cover.

In 1990, he would again photograph the reef, this time showing its decline from his images 30 years prior. The awareness that ensued, rumor has it, influenced national politicians who saw the story to authorize the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary that same year.

He published several ground-breaking books on underwater photography, including one of his most iconic, “Manfish with a Camera,” in which Greenberg described his work as an underwater photojournalist.

Mixed in with his photojournalism, Greenberg also created his iconic waterproof Fish I.D. cards with his wife, Idaz, to help people know what they were looking at underwater. The cards are still used worldwide, and Greenberg personally restocks the stands in the Keys to this day.

So, how do you commemorate and celebrate the man who did so much for diving and showcasing the underwater world? You take him diving, of course, and you let him take pictures.

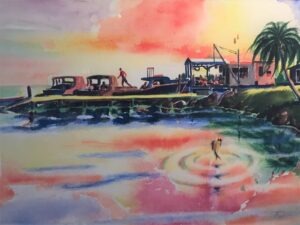

Greenberg recently went out on a very special sunset dive with Quiescence Dive Shop and some legendary friends.

Rob Bleser, the owner of Quiescence, was honored to host the trip out of his dive shop.

“Jerry’s been such an important part of our professional careers, we felt it was only fitting to put this together,” Bleser said. “At his young age of 93, it was our honor and privilege to assist him in getting underwater.”

Greenberg called the dive “just a fun dive and renewing old friendships,” but those out with him knew it was something special.

“We were there to honor a diving legend, his legacy,” said Frazier Nivens, Emmy-award-winning filmmaker known for his work with sharks, who filmed the entire event. “Jerry dives with the old horse collar and a regular old backpack, which was pretty cool. I haven’t seen one of those in a while.”

On their way out, Nivens told Greenberg how his dive shop in the Bahamas used to sell the Fish I.D. cards and how his then 4- or 5-year-old daughter, Jessica, would ask her dad to quiz her on every fish on the card.

“He impacted so many people he didn’t even know,” Nivens said.

Akins, who was also on board, said, “I’ve got copies of those National Geographics from back in the day. There are a few things people of my generation can point to that really inspired their interest in the oceans: Mike Nelson in Sea Hunt, Jacques Cousteau in Calypso and images in NatGeo. I think a lot of people got their inspiration from those images.”

“Before the dive, it was hard to tell if Jerry was excited, thinking about the last 70 years, or focused on what he was going to shoot,” Akins said. “As an underwater photographer, the joy sets in later, after you’re done with the mission.”

When the dive buddies descended on the reef at the Catacombs, Jerry took his fins off and walked around the sand bottom, taking pictures of the reef, the fish and his friends.

“It’s a Jerry thing,” said Akins of the maneuver.

“I’d heard about this before, but never saw it,” said Nivens. “When he took his fins off and he was just walking around the bottom, I thought, ‘Wow. This is really the manfish with a camera.’”

Surfacing, Greenberg said, “That’s the most fun I’ve had in a very long time.”

There was a huge grin on his face, and he was very quiet, Akins added.

“I think that’s when it was setting in,” he said.

Of his life’s work, his legacy, Greenberg refused to even call it that.

“All of it was pleasure. I just did it because I love to do it,” he said. “And I still love it; it’s what drives me.”

He added, “There’s not much I can tell you about my relationship with the reef, with taking pictures of it, ’cause it’s not a word thing. It’s a feeling. It just affected me like great music affects certain people and great art affects others. There are no words to it.”

Jerry Greenberg did the “Jerry thing” and walked in the sand to photograph the reef, avoiding the coral. Video: Frazier Nivens