Amulti-agency team of scientists took over the tanks at Keys Marine Lab in Layton recently for coral “spawning week,” collecting coral eggs and sperm over six nights.

Corals spawn, or sexually reproduce, once a year. On Florida’s reefs, just after the August full moon, mature staghorn and elkhorn corals simultaneously release bundles of egg and sperm, allowing their gametes to mix at the surface and become free-swimming coral larvae — the seed for future reefs.

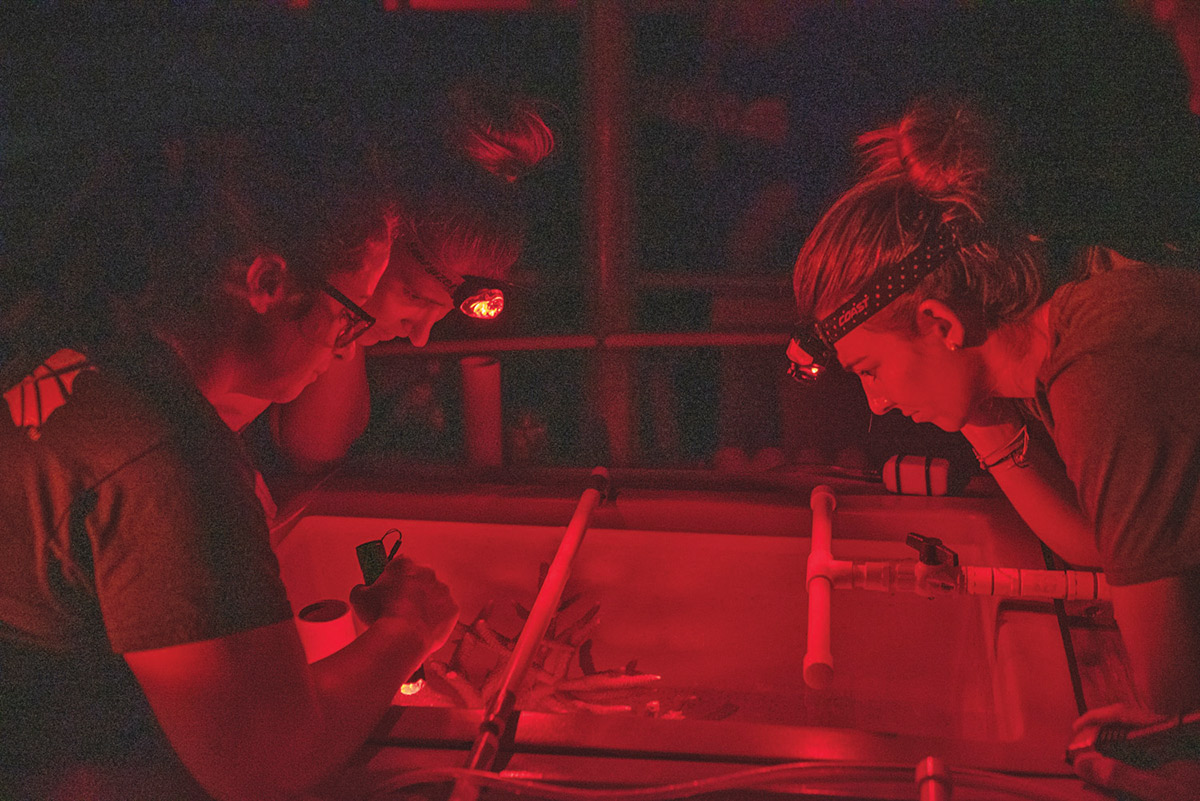

For the scientists at KML, spawning week looked a little bit different. Rather than diving in the ocean to collect gametes, the researchers camped out at KML night after night, waiting for corals to spawn in the land-based tanks.

The tanks contained 12 genotypes of staghorn and six genotypes of elkhorn corals from Coral Restoration Foundation’s Coral Tree Nursery in Tavernier. After several nights of waiting, the corals did spawn and researchers scooped up the “bundles of joy” to begin their experiments immediately in the dry lab. Gametes released at KML were easily and efficiently collected for research and rearing, and the agencies ran their experiments simultaneously. All the research aimed, in one way or another, to restore the Florida Reef Tract.

The spawning team, led by Rachel Serafin, coral biologist with Florida Aquarium (FLAQ), included researchers from KML, University of South Florida/Florida Institute of Oceanography, Georgia Aquarium, Nova Southeastern University, NOAA, SeaWorld, Southeast Zoo Alliance for Reproduction and Conservation (SEZARC), and the University of Florida. Each institution focused on a different aspect of spawning.

“We’ve lost massive portions of our coral populations,” said Serafin, “to the point where reproductive success in the wild has declined to little to none.”

This decline in the reefs has led to a very shallow gene pool where corals might only asexually reproduce by fragmentation. Craig Johnson, senior biologist at FLAQ, explained how spawning populations are too far apart for their gametes to meet in the ocean. As a result, there are no new genotypes being created through sexual reproduction.

These researchers are combating that by playing matchmaker and bringing gametes together in the lab to create more genetic variation. This diversity creates stronger colonies and a more natural reef system, said Serafin.

Serafin’s team studied the link between fertilization rate and embryo development to learn more about what factors influence successful fertilization and coral recruit growth. Last year, FLAQ’s team used gametes from spawning at CRF’s nursery to create 1,500 new genotypes through cross-breeding. Around 3,000 individual corals from that effort were transferred back to the Center for Conservation at FLAQ for eight months before being returned to CRF’s nursery.

This year, the FLAQ team hoped to breed and bring back 5,000 staghorn and 5,000 elkhorn recruits to raise at FLAQ. The goal, again, is to return these corals to CRF for continued growth and eventual outplanting back onto the reef. Johnson explained their work as “trying to get ahead of the extinction curve” by cross-breeding the endangered corals in house.

Other researchers focused on different methods of preserving genetic variation. SEZARC’s team cryo-froze gametes from CRF’s corals to add to their genome resource bank. Ashley O’Toole, gamete lab technician with SEZARC, explained, “These are all new genotypes we’re freezing that weren’t represented in our bank before, but now they will be.”

Cayman Adams, her colleague and research lab manager, explained how that genetic diversity was an “insurance policy” for the future in case the worst happens and populations crash. In that case, frozen coral sperm from SEZARC’s bank could be thawed to create more genetic mixes.

NOAA and the College of Charleston analyzed whether fertilization success is linked to genetic relatedness. Lisa May, laboratory manager for NOAA’s Coral Health and Disease Program, explained the bigger goal: “If we can link this science to restoration efforts, we can pick and choose which genets to restore to boost natural spawning and restore our reefs more quickly.”

A long-time researcher in coral spawning, Justin Zimmerman, aquarium supervisor at SeaWorld Orlando, described why this year’s spawning efforts had increased urgency: “Stony coral tissue loss disease in the last two years, I realized these corals won’t be around forever. It’s grim.

“That’s why we have so many people involved here,” Zimmerman said. “We need everyone to bring their expertise. The partnership makes us stronger, helps advance science, and gives the corals a better chance.”