There are hundreds of species of seaweeds in the genus Sargassum, which is a brown macroalgae found all over the globe. In the Florida Keys, we have at least two local species that grow from holdfasts attached to the bottom in shallow waters, Sargassum pteropleuron and Sargassum filipendula.

Unlike plants, seaweeds have blades instead of leaves and stipes instead of stems, and many have a distinctive berry-like float, which is a gas-filled air bladder called a pneumatocyst that keeps these macroalgae upright and swaying in the currents.

Most people are familiar with the pelagic species of seaweed: these unique free-floating species are called Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans and live on the surface of the ocean far out at sea. Offshore fishers are familiar with these vast mats of floating sargassum they call the weedline because when they find it, it usually means “fish-on.” This is undoubtedly a fabulous place to sportfish for mahi, wahoo and tripletail.

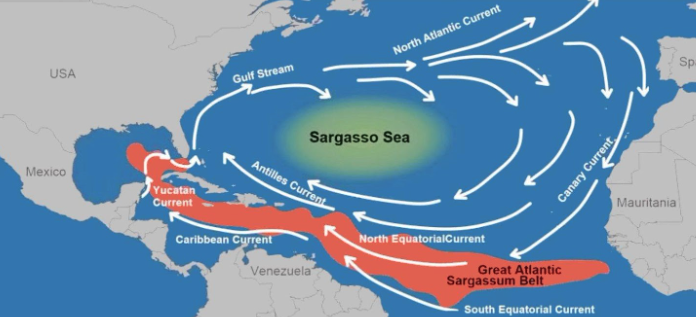

Historically, these two species of floating sargassum were only found within the Sargasso Sea, which is an area of open ocean between the eastern U.S. and western Africa above the Tropic of Cancer. The Sargasso Sea is not a true sea, but an area within the Atlantic Ocean gyre constrained by the Gulf Stream, Canary Current, North Atlantic Current and the Northern Equatorial Current. Often eddies break off these gyres and easterly winds, currents and the tides bring these two species of sargassum ashore. The Sargasso Sea is an incredibly important ecosystem and essential habitat for more than 100 species of fish. It provides habitat and forage for invertebrates, birds and sea turtles.

Recently, scientists have documented a “Sargasso Sea” called the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, a brand-new area below the equator in the Atlantic Ocean between western Africa and South America. It is hypothesized the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt was created during an extreme North Atlantic oscillation event between 2009-2010, wherein rafts of sargassum were ultimately driven south and found the warm currents, ample sunshine and nutrients a very hospitable environment to grow exponentially.

Since 2011, huge influxes of these two pelagic sargassum species growing south of the equator started inundating Florida’s coast. Whether or not the sargassum is pushed ashore depends upon prevailing south to southeastern winds, and it’s usually seen between June through August (it does not happen in the Florida Keys every year). The last big influx in the Florida Keys was in 2019 when we experienced record accumulations during the summer months. Unfortunately, when these seaweeds are driven ashore they can create massive environmental and economic costs. These inundations are in excess of historical amounts and many Caribbean islands and Mexico have been plagued by tons and tons washing ashore, which has wreaked havoc on fishing and tourism. This has been called the largest macroalgae bloom in the world, over 5,500 miles across with 20 million tons of algae biomass.

Historically, washed-up sargassum is one of the ways beaches were created in the Florida Keys, as the accumulation of seaweed along the shoreline helps to keep the sand from eroding and provides nutrients to help enrich the soil. But when the sargassum encounters a seawall or a canal, it decays, sinks and stinks. Piles of sargassum on the beach can discourage nesting female birds and smother sea turtle nests.

Massive rafts of floating sargassum can block sunlight to seagrass beds and decomposition decreases dissolved oxygen levels, which has caused localized fish kills. In moderation, pelagic sargassum serves as a vital ecosystem component, but in excessive amounts, it can disrupt local marine ecosystems, diminish water quality and degrade habitat.

The Monroe County Extension Service has been working with the University of South Florida Optical Oceanography Lab at the College of Marine Science on a new tool that uses satellites to track sargassum on a finer scale than was previously available. Just recently USF has upgraded its ability to detect sargassum and forecast to an area the size of a football field for the Upper, Middle and Lower Keys.

In the coming months, scientists will be expanding their ability to predict sargassum inundations and expanding out to the Dry Tortugas. We plan to use this tool to be proactive in managing the effects when we know large aggregations of sargassum are en route to the Florida Keys.