“If you look at this as just a wreck to dive on, you’re missing the whole story,” said Kamau Sadiki. “Each of these vessels has a powerful and tremendous story to tell, and the only way to tell it is to interrogate it, investigate it, sense it and feel it. Collect the data and try to make sense of it.”

The Diving with a Purpose (DWP) lead instructor and board member reflected on his experiences diving on shipwrecks around the world, including several that were directly involved with the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

DWP is a non-profit organization providing training, education and archeological fieldwork support for submerged heritage preservation and conservation projects. DWP has a particular focus on the African Diaspora.

For example, the sanctuary estimates there are 700 to 800 archeological sites throughout our island chain, most of which haven’t been properly documented or explored. DWP and NOAA have teamed up over the last decade to search for and map other Keys shipwrecks – including the City of Washington and the infamous Guerrero slave ship.

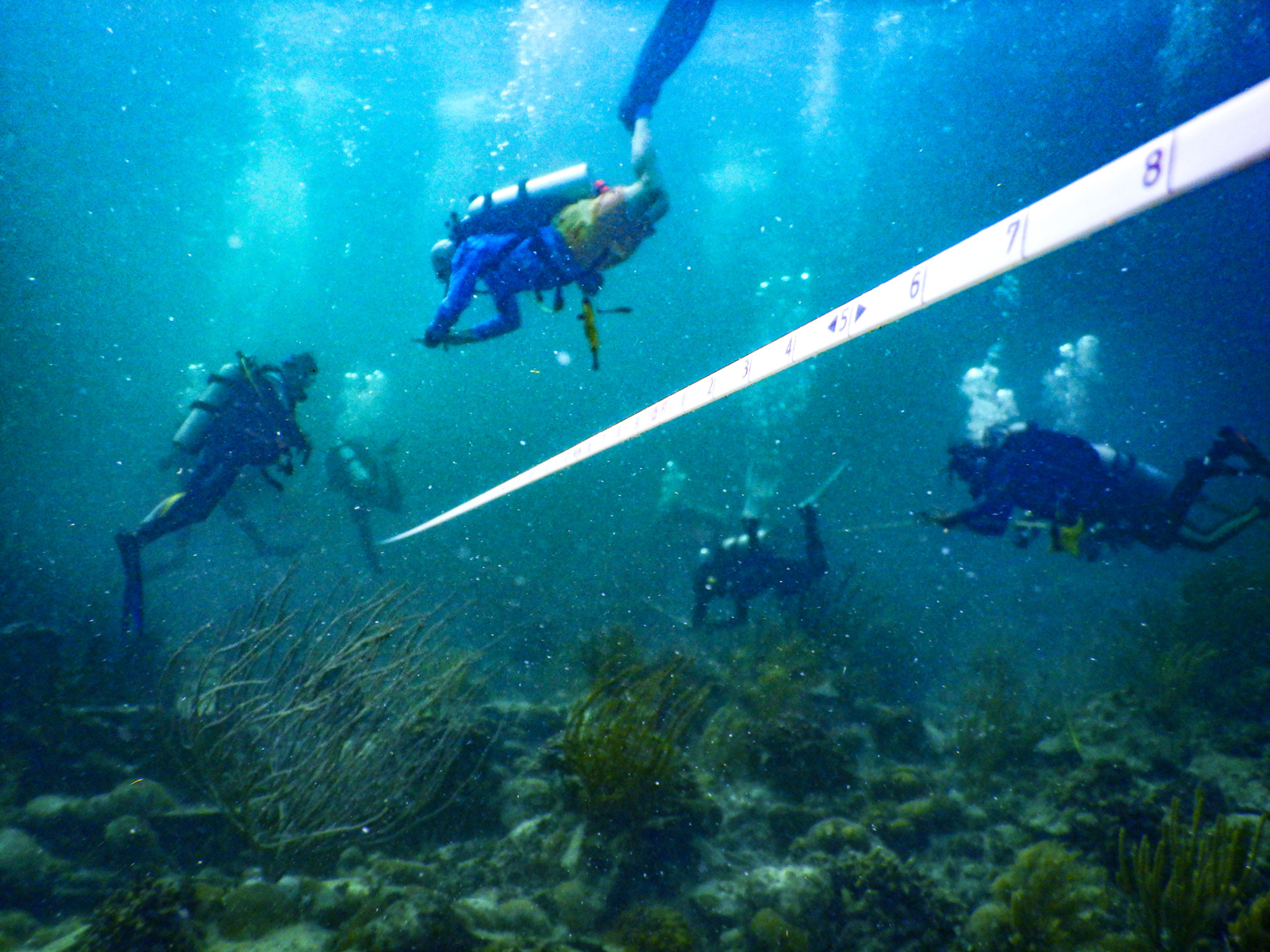

In June, Sadiki and his DWP dive team traveled to the Florida Keys to help NOAA document and map yet another shipwreck in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Their work will help NOAA’s Matthew Lawrence and his maritime heritage team understand the history – and mystery – behind the vessel’s untimely sinking.

The Brick Barge, as the wreck is currently known, sits in 20 feet of water in the Hen and Chickens Sanctuary Preservation Area off Plantation Key. It’s believed the vessel sank in 1949 en route to Key West.

“This is a neat shipwreck because every aspect is local,” Lawrence told the Weekly. “It sank here in the Upper Keys, and the bricks it was carrying ended up in homes at a certain intersection of Key West – we just don’t know exactly where, yet.”

Some details don’t add up perfectly, Lawrence added. First off, the shape of the wreck isn’t a traditional, rectangular “barge shape.” There is one pointy end, which, to Lawrence, indicates that it might have been a steamship or sailing vessel before it was a barge.

Secondly, most ships with pointy ends have two of them. The Brick Barge has only one, which tells the sanctuary team that divers are looking at only half of the vessel on the seafloor. The original ship was probably twice the length of what is still visible. The barge likely ran aground and sank close to where the wreckage sits today. Then, Lawrence suspects, the owners raised half the vessel – the half containing the precious brick cargo – leaving one pointy end and half a vessel at the bottom of the sea.

Finally, using old newspaper reports, the sanctuary team has pieced together a spotty history. There is news of a barge breaking free from a tug and drifting inshore before sinking. That aligns. There are also stories of a father-son duo who were on the barge and who clung to a mast overnight to survive. The son eventually swam to shore to find rescuers to come back for his dad.

Chronologically, here’s where the discrepancies begin. While the bricks did make it to Key West, a different newspaper report claims they did so on said barge. Because at least half of it is still sitting on the seafloor, we know “that’s just not jiving with what we see here, so there’s a hidden history we’re trying to uncover,” Lawrence said.

“What happened thereafter is a mystery. It’s just an unusual situation,” the archeologist added. “But, once we map it, we can get a better idea of when it was built, what it might have been and, ultimately, what happened to it.”

Sadiki, tasked with drawing the bow section of the ship as it sits on the seafloor, took special care to document everything in exquisite and exact detail. You never know what small detail might lead an archeologist like Lawrence to learn something new about the vessel, he said. The data will be compiled and converted into a shipwreck map, which is made available to the public and which helps shed light on the origins of the wreck.

In the end, it’s really the stories behind the shipwrecks that matter, and uncovering those allows us to appreciate who they were and how they connect to us now, Sadiki said. Lawrence agreed, noting how a rewarding part of his job is to “reveal the people’s stories that didn’t make it into history books” and to “connect people here in the Keys to their history.”

As for the Brick Barge, we’ll have to wait for the map, the history and the stories to reveal just how those bricks got to Key West in the end.