Dr. Douglas Wartzok, provost emeritus and professor emeritus of biological sciences at Florida International University (FIU), will present at the monthly Ocean Life Lecture Series on Thursday, Oct. 24 at Murray Nelson Government Center. His talk will focus on the issue of noise in the ocean, especially in terms of sonar, seismic, and marine mammals.

“Jacques Cousteau once talked about the quiet ocean. Well, it’s not really quiet,” explains Wartzok.

“The ocean is reasonably noisy, and the animals have learned to adapt to that,” he says. However, in the 1960s, the navy began to use sonar to locate things and to explore the ocean floor. Unfortunately for many whales and marine mammals, the frequency and sound of sonar is similar to the sounds of their predators – killer whales, explains Wartzok.

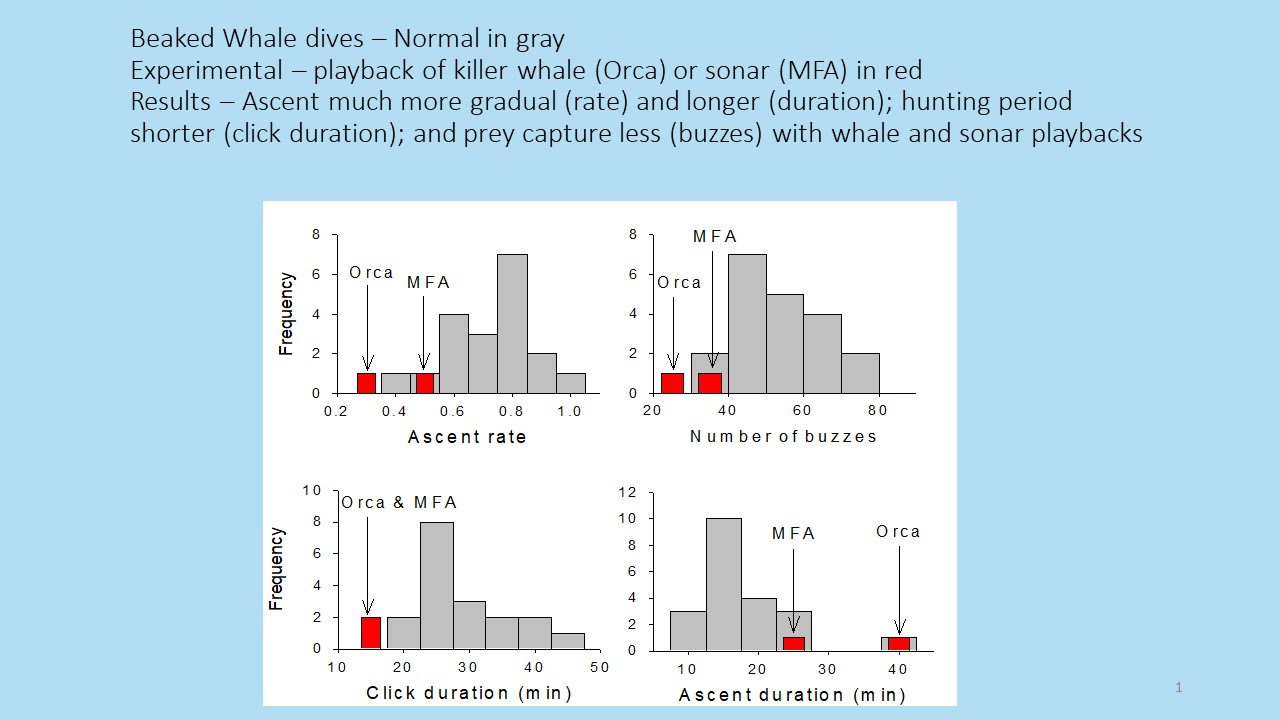

“The emerging hypothesis is that sonar is viewed by these animals as a super-predator. That’s why they respond as they do,” continues Wartzok. He explains how whales will ascent and descend more slowly than in cases where no sonar interferes with their diving. And, he adds, whales will change their behavior to try and move away toward beaches. Then, they get stuck. “Deep-diving whales don’t know what to do, and when they encounter a gently-sloping beach they don’t have experiences to know how to extract themselves,” he explains. “Then, in some cases, when they swim rapidly they end up overheating themselves, if they can’t dump all that heat into colder, deeper water, they basically die of heat stress at the surface.”

Wartzok also examines seismic activities, wherein sawed-off air guns send a strong pulse through the earth. Trailing a hydrophone behind the ship, researchers are then able to get an idea of whether there are any oil pockets at the sea floor. “There is no evidence of animals dying after seismic, but the technology has caused animals to forage less and swim at reduced speeds. Wartzok offers a metaphor. He says, “It’s like having a music festival in your backyard. It doesn’t kill you, but it will annoy you extensively. That’s what the whales are experiencing.”

He concludes by trying to keep it all in perspective. While roughly 100 whales total have been injured by sonar since began in the 1960s, somewhere close to 600,000 die every year as fishermen’s bycatch. “I think it’s important that people realize that worldwide, fisheries contribute close to 1,000 times the deaths,” adds Wartzok.

He also brought up these points on a national committee, not to discount the effects of sonar and seismic, but rather to view them within a broader context of harms done to the oceans. This concept is referred to as the cumulative impact over multiple modalities and over time. “Look at the cumulative effect of all we’ve done,” he says. “Sound alone won’t drive these animals to extinction, but sound plus pollution plus fisheries bycatch? For some populations, the impact of all three might not be something they can survive.”

Wartzok’s lecture was held at 7 p.m. at the Murray Nelson Government Center in Key Largo on Thursday, Oct. 24.