For South Florida’s commercial fishermen, the effects of red tides on their operations have become a grim annual reality.

The tides, named for when overproduction of the harmful algae Karenia brevis leaves significant swaths of red or brown water, can cause fish kills when toxins produced by the algae, known as brevetoxins, affect the central nervous systems of fish. Though usually temporary, the same aerosolized brevetoxins can cause coughing and sneezing in humans, and swimming in affected waters can cause skin irritation and burning eyes.

The blooms occur naturally, beginning in the Gulf of Mexico before moving inshore. From there, human impacts may have an effect on the final outcome – but the question of how, and to what degree, is difficult to answer and changes every year.

Reports of red tides typically start in the fall and clear out by January or February, but some can stay longer and leave greater destruction in their wake. Cold spells, like those experienced in the Keys in late 2024 and early 2025, tend to correlate with blooms staying offshore and moving farther south, while warm temperatures tend to push the affected areas north and inshore.

The algae thrive in nutrient-rich waters, such as those left in the churned-up wakes of Hurricanes Helene and Milton in 2024. But those nutrients can also come from runoff containing chemicals from farms, factories, sewage plants and other sources – leaving some pointing the finger at nitrogen-rich sources such as discharges from Lake Okeechobee.

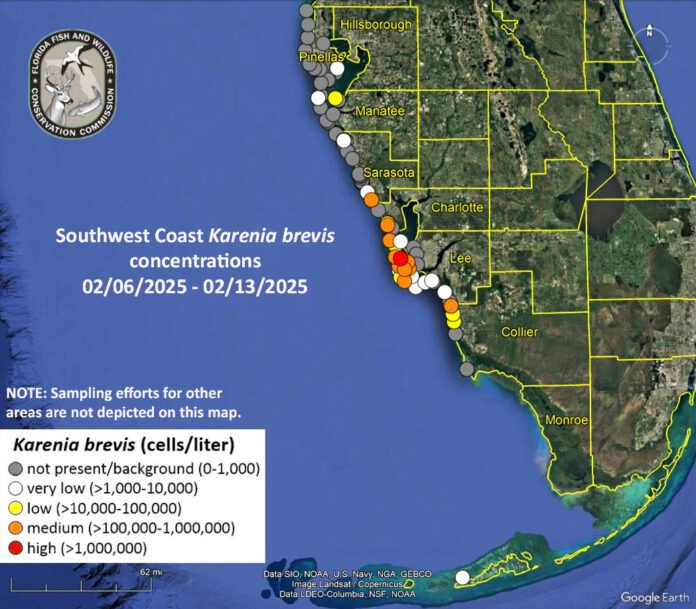

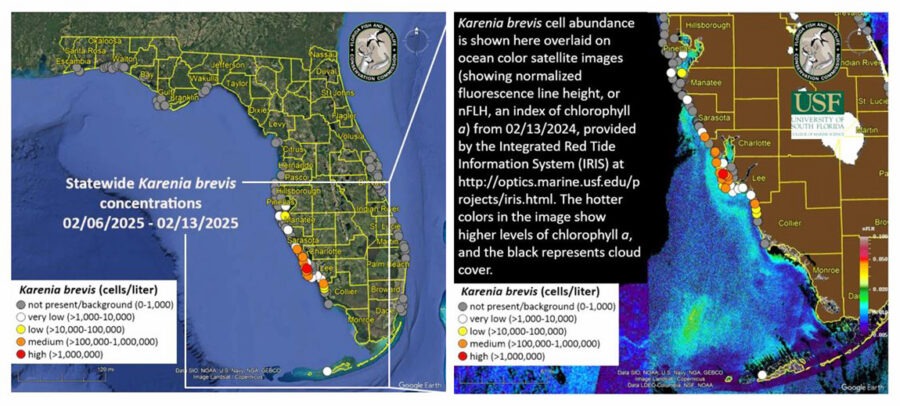

In late January, an advisory from the Florida Department of Health confirmed the presence of red tide at Marquesas and Marvin Key in Monroe County.

Water samples taken roughly 10 miles north of Content Key on Feb. 11 by FWC showed “very low” levels of the algae – between 1,000 and 10,000 algal cells per liter. Two days later, three samples taken between 10 and 14 miles north of Bahia Honda showed “low” concentrations of between 10,000 and 100,000 cells per liter.

So what’s causing it?

Mike Parsons is the director of the Florida Gulf Coast University’s Vester Field Station. He told the Weekly it can be difficult to link the bloom events definitively to hurricanes or any other single cause.

“After Irma, we had a very big red tide event and a blue-green algal bloom event,” he said. “(But) after Ian, which was a much more damaging storm to us (in Cape Coral), we didn’t have as bad of a red tide.

“All the data we have points to these blooms naturally starting 50 to 100 miles offshore, then moving inshore,” he added. “It’s already a naturally-occurring event, but how do we then influence that bloom once it comes close enough where our activities and runoff and water quality can have an influence? If it was an easy answer, we would have figured it out a long time ago.”

Kate Hubbard is the director for FWC’s center for red tide research. In addition to increased baseline monitoring in recent years for bloom events, her team works with modelers at the University of South Florida to add increasingly complex layers to models for ocean circulation, adding in biological and eventually chemical components. But those complexities, she told the Weekly, add nuance when looking for a simplified answer for the causes behind the blooms.

“We’re able to model and say, ‘If we change these drivers, can we replicate this bloom? If not, what else do we need to think about?’” she said. “We’re making a lot of progress to be able to address that complexity, but because it is so complex, I don’t want to give a simple answer, because there really isn’t one.”

At the time of Hubbard’s Feb. 13 interview with the Weekly, circulations were expected to continue pushing the bloom north and west over the next few days.

“If it keeps moving out west, then it may get entrained in some of the currents out there, and then it may be less likely to impact the Keys,” she said. “But it could just as easily be in a situation where the opposite happens too.”

“If it lingers and potentially intensifies, we should be prepared for the consequences of that, be it the fish kills or other things,” said Parsons.

Fishermen need help

In 2019, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the Florida Red Tide Mitigation and Technology Development Initiative into law, providing $18 million over six years to aid in development of mitigation approaches and technology. In 2024, he removed the initiative’s original sunset clause to continue the funding. Still, those directly affected by the annual blooms say they’ll need more of a helping hand to survive the events moving forward.

“I have a boat, and we’re probably at a 50% reduction this year between the hurricanes and red tides,” Jerome Young, the executive director of the Florida Keys Commercial Fishing Association, told the Weekly. He said the areas of affected water inside Keys fishermen’s normal fishing grounds can be more than 60 miles across – and it’s not always feasible to put in the work and funds required to move traps.

“Most guys are probably at least 50% down, on top of all the repairs and loss of traps from the hurricanes. It’s been one of the worst lobster seasons for as long as I’ve been in the business,” he said. “Now that it looks like it’s going to continue every year, we’re hoping we can establish something for disaster relief, just like we do for major hurricanes.”

Continued reporting is key

In 2024, the “spinning fish” phenomenon saw a deluge of public reports documenting the details and locations of affected animals. Concerned that this event may have caused “reporting fatigue,” Lower Keys Guides Association executive director Allison Delashmitt said that continued submissions are vital in aiding investigators monitoring the red tide impacts in the Keys.

“It’s important to report even if you see the bloom in the same place on different days. The reporting gives us a real-time understanding of what’s happening where and the trends of movement,” she said. “But if funding is needed for additional research and sampling efforts, the reports can help give an understanding of how bad it really is, and that will help for future support.”

The quick hits: what you need to know

- Don’t wade or swim in or around areas visibly affected by red tide, or where signs note the presence of red tide.

- Wash your skin and clothing with soap and fresh water if you have had recent contact with red tide, especially if your skin is easily irritated.

- Harvest areas for filter-feeding shellfish, which can accumulate toxins, are closely monitored by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer services, and closed when necessary. Do not harvest shellfish or distressed or dead fish from affected areas.

- The filets of fish and meat of crabs and lobsters are generally safe to eat, but avoid consuming the whole fish or other organs not typically eaten, such as the hepatopancreas in lobster (sometimes referred to as tomalley or the “guacamole” in the lobster’s head).

- To view red tide concentrations in recent water samples, follow FWC’s weekly red tide updates.