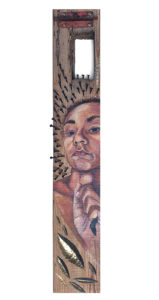

Some time after Hurricane Irma in 2017, artist Sally Binard found herself sitting on the floor of her new place, chisel in hand, staring at a two-foot chunk of Dade County pine with a mortise hole squared out at the top, trying to figure it all out.

She’d never really done mixed media before. Everything so far had been painting, sketching, pottery, maybe a little embroidery.

But so much was in flux. Her marriage had just ended. Irma had destroyed her Summerland Key studio, flooding it with 4 or 5 feet of water, destroying her kiln, her paints, brushes, blank canvases. And all those paintings, so much work, warped, stained, covered in dirt and mold. Ruined.

After years of being able to retreat to the quiet up the Keys, she was living in the never-ending bustle of Key West, renting space from Michel Delgado – a painter and sculptor who doesn’t make much distinction between his studio life and his home life. The place looked a bit like a Senegalese bazaar, she thought, or what she imagined a Senegalese bazaar looked like, anyhow.

“Things just got different. Real different,” Binard said.

She started chiseling out shapes in the wood, then hammering in nails, screwing down the slide from a deadbolt, painting a female figure that turned out to be herself – her face and her neck, her hand holding several small feathers.

“I was not at my best,” she said. “But the piece just came out so fluidly.”

On the lower half of the board, inspired by the work of Lauren McAloon, she created a series of boat shapes and lined them with gold leaf.

The result was, “Afraid to Launch,” and it marked a departure for her. It was the beginning of an exploration of her racial identity — her father was from Belgium, her mother Haiti — and an analysis of things that didn’t bother her when she was young — living in a mostly white world — but had begun to trouble her in recent years, and in the different racial context of Florida and the Keys.

A few months after the storm, Binard saw an ad on the Florida Keys Council of the Arts webpage seeking submissions from artists from Florida and the Caribbean who were affected by recent hurricanes. She applied largely because it came with a small stipend, a hotel room, and round-trip tickets to Charlottesville, Virginia, where her sisters lived. (She hadn’t seen them for a while.) But she found herself profoundly changed by the arts conference, which included other artists from St. Croix and Puerto Rico.

“I just learned so much from the other artists and saw the power of what they – and now I can include myself – were doing. It was a conversation that was not just about hanging a pretty picture on the wall. And that’s just when I was hooked on art being something bigger than aesthetics and pretty stuff, and about the function that we can play in social change or environmental change,” Binard said.

She began creating the pieces that would become the basis for her show “None of the Above,” which was on display at The Studios of Key West in January of this year.

Binard grew up in a military family, much younger than any of her five half-siblings, the only one who wasn’t blonde-haired and blue-eyed. They moved every few years: Wisconsin,

Virginia, Puerto Rico, Iceland, Washington, D.C., Belgium…

“You just learn how to entertain yourself when you’re constantly in a new environment,” she said. Mostly she did it by hiding under desks and drawing.

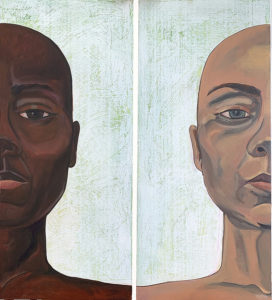

black. Eventually it dawns on the viewer that apart from skin tone and eye color, the two figures are essentially identical. SALLY BINARD/Contributed

“You could kind of drop me anywhere and I’d be fine. My dad would send me to Belgium at 13 by myself. I was running around Europe on trains and, like, Paris, at 15 by myself,” she said.

“I didn’t find anything scary because you just adapt.”

Binard came to the Keys because she wanted to make art and live on a boat. But she was also pragmatic.

“I started college as a math major and then realized that wouldn’t get me on a boat. So I switched to marine science, figuring I could work on a boat that way,” she said.

She graduated from the University of South Florida and took a contract job with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission doing fish surveys out of Marathon. She ended up buying a sailboat, but living on a different boat.

After the FWC contract, she took up graphic design and bartending, working at Rick’s on Duval Street for six years while earning a master’s degree in psychology from California Coast University.

She also began taking art classes at what was then called Florida Keys Community College – sculpture, pottery, figure drawing. She took some private classes with wildlife artist Cynthia Kulp on how to work with oil paints.

She did some illustration work – wildlife drawings for Bill Keogh’s Florida Keys Paddling Guide, scientific illustration-themed Christmas cards for Mote Marine Laboratory, technical illustrations of artifacts for the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum.

She had her first solo show at The Art of Elton, a hair salon in Bahama Village. There were six pieces, she recalls, three of which sold.

She painted portraits of chickens for a while for the Funky Chicken shop on Duval Street, and showed her work in several other Keys galleries.

She built up an Instagram account, @flamingoandflower, with close to 6,000 followers, through which she sold tiny handmade pots filled with tiny succulents, but has since let the account go fallow. (It’s hard to gain much traction in the world making tiny pots.)

“None of the Above” was booked at TSKW two years ago, pushed back on the calendar, like

so many things, by the exigencies of COVID-19, given a deeper resonance during the delay, like so many things, by the death of George Floyd and the summer’s Black Lives Matter protests.

Everyone’s work, to a degree, is about their identity. You can’t paint, sculpt, write, take a picture, sing, whatever, without leaving traces of who you are. But “None of the Above” wasn’t sidelong or incidental. It was head-on, a heterogeneous deconstruction and a reconstruction all at once.

In “One or the Other / Choose, and Choose Now” Binard paints two figures, one white, one black, and eventually it dawns on the viewer, perhaps not quickly enough, that apart from skin tone and eye color, the two figures are essentially identical.

In “Reclamation,” Binard returns the viewer’s gaze from a piece of oriented strand board riddled with neat holes, her head haloed by screws from an old hard drive, her arms wide, resting on a long bar, a posture that is simultaneously cruciform, confident and defiant.

Nails are used repeatedly throughout the works in disconcerting ways, piercing the plane of the art, piercing the skin of the subjects, their exit points sometimes encircled in more goldleaf.

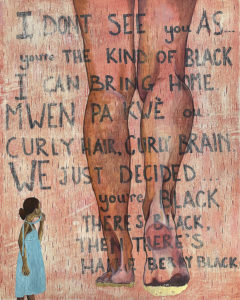

Arguably the most unsettling piece is “1000 cuts, 1001 heals,” a painting of the back of her legs overlaid with the appraisals people have made of her body, her race, her personhood.

“You’re the kind of black I can bring home,” “Curly hair, curly brain,” “There’s black and there’s Halle Berry black.” In the lower left corner a small girl in a blue dress looks on.

You can see the images on The Studios of Key West website at tskw.org, and several works are now on display at Harrison Gallery on White Street.

Binard has moved on, creating more paintings of chickens, though this time with a feminist bent. (There are a lot of roosters involved.) She’s also working on a project creating visual

Back stories for the lives of people often depicted as little more than stick figures on slave ships.

I asked Binard if “None of the Above” had been cathartic for her.

“I thought at the end, I’d be like, all right, I solved this thing. I’m good. And I know enough, with therapy and psychology, that there’s really no end. You resolve things, but they will come in another layer or in a different form and you’ll have to deal with it again,” she said.

“The realization I came to is, the inner conflict I have with this dynamic of my racial makeup– sometimes I’m cool with it, sometimes I’m not. And I just keep walking. It’s a really simple realization. But it felt good to get it out on paper. Or wood.”