In the mid to late 1800s, Captain Ben Baker was the King of the Florida Wreckers. His 13-ton, three-masted schooner “Rapid” was the pride of the Baker Wrecking Company.

In 1850, he operated out of Key West and lived in a large, two-story house on the corner of Whitehead and Caroline streets. However, shipwrecking was rarely full-time work, and most wreckers maintained alternative sources of revenue. Baker’s side hustle became pineapples.

In the late 1850s, Baker and his sons sailed for the Upper Keys where they cleared land on Plantation Key and Key Largo. When the fields were ready, Baker left for Havana and purchased as many as 6,000 pineapple slips and suckers to plant on his lands. A firsthand account of Baker’s pineapple operation, written by Dr. J.B. Holder, appeared in an 1871 edition of Harper’s Weekly: “Plantation Key has considerable good soil; many of the trees here are seventy or eighty feet in height. Here was a large plantation of cocoa-nut palms, several hundred in number, and a patch of young pineapples. A late paper gives the account of the products of his patch, which have been materially increased since the writer was there. Mr. Baker, the owner, who resides at Key West, is reported to have realized seven thousand dollars this season from his crop of pine-apples. The great drawback is the prevalence of mosquitoes, throughout the whole year, in such swarms that few persons are willing to suffer the annoyance; otherwise these keys would richly reward the cultivator.”

Today, the $7,000 Baker earned from his pineapple fields from that season’s haul would be worth about $150,000, and that seems like a pretty good side hustle. Before the fruit was shipped to market, it was picked two weeks early. The green pineapples were packed in crates and shipped below deck in cargo holds. As the ship sailed to market, the fruit continued to ripen. On an average trip, 25 percent of the cargo rotted at sea.

When Henry Flagler’s railroad pushed down the east coast to Miami in 1896, the link between the field and market was drastically reduced. The railroad provided a quicker and more reliable mode of transportation. Now fruit could be loaded on the 5 a.m. train departing Miami on Monday and appear in New York markets by Thursday.

Flagler’s train did not stop at Miami, and the line continued pushing south across the Florida Keys until it came to its terminus at Key West. The tracks and bridges took years to build. The work was done piecemeal, with railroad construction sites operating up and down the Keys simultaneously. In total, 82 work camps were established between Key Largo and Key West.

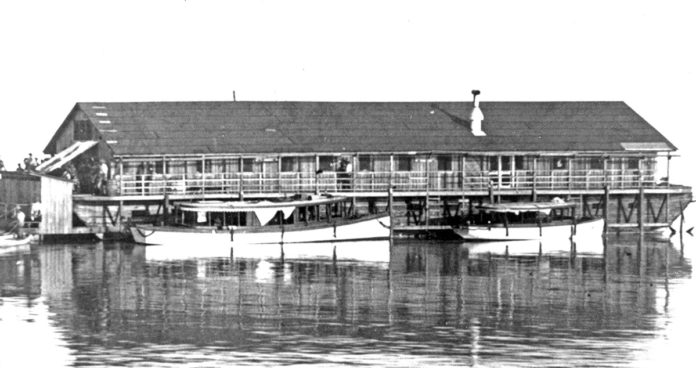

On Oct. 17, 1906, the eye of a Category 2 hurricane crossed Long Key, where one of those work camps was, housing hundreds of railroad employees. Many of the men were housed in floating dorm rooms called quarter boats. On the shores of Long Key, where the Long Key Fishing Camp would come to national attention a few years later, two of these quarter boats were secured with six mooring lines and an anchor.

When the hurricane blew ashore at about 5 a.m., the line anchoring both houseboats snapped, and the two vessels were tossed where the storm dictated. One of the houseboats washed out into the Gulf only to be pushed back onshore. House Boat No. 4, on the other hand, was blown out into the Atlantic. The vessel was pounded by wind and storm-driven swells until it began to break apart. Only 83 of the 150 men on board survived. The situation was no better at a Lower Matecumbe work camp where two houseboats, each with 45 FEC workers on board, were also carried out to sea.

The storm accounted for some 193 deaths. The hurricane also inundated the Upper Keys with a tidal surge that swamped the pineapple fields of the Upper Keys, including fields on Key Largo and Plantation Key. The 1906 hurricane also marked the beginning of the end of the island chain’s pineapple industry.

When daily railroad service was established between Miami and Knights Key, at the foot of what is today the Seven Mile Bridge, in 1908, Cuban pineapples began competing with produce grown by Keys farmers. Shipped from Havana, the pineapples were loaded onto refrigerated rail cars called the Cuban Fruit Express, capable of delivering pineapples to Chicago in 72 hours.

Salting wounds inflicted on local farmers as the result of hurricane and a subsequent pineapple blight, the Florida East Coast Railway taxed Cuban farmers at a lower rate than local farmers.

Hurricanes in 1909 and 1910 would continue to devastate the pineapple fields of the Upper Keys and swing the door open wider for Cuban pineapple exports. By 1909, cheaper Cuban pineapples flooded American markets and, by 1910, pineapple farming was on its way to becoming another failed Florida Keys industry.