As the new hurricane season rolls in on Thursday, June 1, residents of the Florida Keys will likely remember Hurricane Ian, a Category 4 storm that tracked just west of the island chain last fall. At the peak of Ian, the offshore wave heights at Satan Shoal, 14 miles from Key West, exceeded 26 feet, yet the Keys did not see waves anywhere near this large. Where did all that wave energy go?

The answer lies in the offshore barrier reefs, the subject of a new research project focused on how coral restoration may enhance wave dissipation. “Without the barrier reef system, much of the Keys would be exposed to the full brunt of ocean swell,” said Jim Hench, an associate professor of oceanography at Duke University. “But the reefs, through their complex structure and frictional properties, interact with the waves, convert wave energy into turbulent energy, and then heat. That’s the dissipation mechanism.”

The physics of these processes has been studied along flat sandy beaches, but relatively little work has been done applying these theories to the steep complex topography of coral reefs along the Keys, particularly under extreme wave events — until Ian.

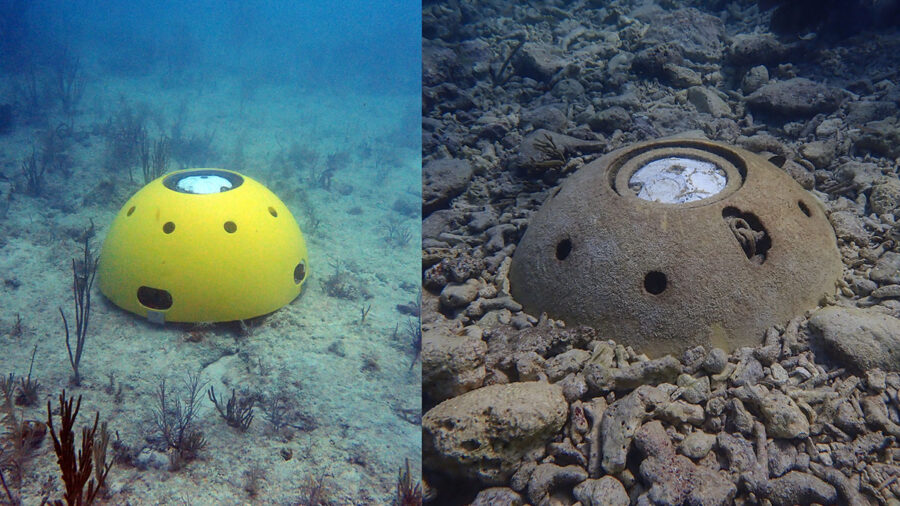

In August 2021, Hench set out an array of 26 sensors along one kilometer at Eastern Dry Rocks reef site (EDR) for the Mission: Iconic Reefs coral restoration program, which is managed by NOAA’s Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. EDR, seven miles south of Key West, is a focal site for coral outplants, and Hench’s project is designed to measure the degree to which restoration improves the reef’s ability to reduce the size of waves, or what scientists call wave attenuation. Ian provided the perfect storm for providing insights into this problem, and having an array of autonomous sensors in the ocean at the right place and time.

“It was amazing to get these data during an active hurricane and have direct measurements of how the wave energy transforms across the reef,” said Hench. “I was impressed by the size of the waves in that shallow of water.” As the waves began to interact with the shallow reef structure at EDR, the reef swallowed the energy. Hench used the new data to calculate changes in wave energy, and discovered more than a 90% reduction in wave energy over less than a kilometer of reef.

“When the water gets shallow enough, waves break,” Hench explains. “We know that, but what surprised me was the amount of dissipation across the shallow forereef. … As the waves approach the reef, the wave orbitals are really energetic while interacting with the bottom roughness — that’s a really good recipe to dissipate wave energy in a relatively small area. This has significant implications for where reef restoration might be best sited to maximize wave attenuation, taking advantage of when the waves are most energetic and using that enhanced roughness to dissipate the wave energy.”

Mission: Iconic Reefs is doing just that. The westernmost site of the seven iconic reefs, Eastern Dry Rocks has been enhanced with more than 11,000 elkhorn and staghorn coral outplants since December 2019, when the 20-year, $100-million program was launched.

“This is the first study in the Florida Keys that provides us with a quantitative value of the importance of our offshore reef system at reducing wave energy,” said Andy Bruckner, the sanctuary’s chief scientist. “Over time, as the restored elkhorn coral increases in size, we will be able to determine how much we are able to enhance the reef’s ability to protect coastlines from storms through restoration activities.”

While the reef diminished the height of Ian’s waves, the volume of water being pushed by hurricane-force winds, known as storm surge, continued to move inland and Key West experienced flooding — a reminder that reefs are not an end-all solution to hurricane protection. The sensors will remain on watch at EDR until 2025, measuring wave pressure eight times per second, in addition to monitoring water temperature and currents.

“We have long understood the ecological and economic value of the only barrier reef in the continental United States,” said Sarah Fangman, superintendent of the sanctuary. “But seeing it quantified in this way inspires us to work even harder to restore these reefs for everyone who has a stake in their survival.”

The research is funded by grants from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and NOAA’s National Centers for Ocean Coastal Science, facilitated by the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation and permitted by Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, as well as the Honda Marine Science Foundation, and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

— Contributed