With the release of an environmental impact statement and management plan reflecting the highly-anticipated Restoration Blueprint for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), the Florida Keys are just months away from a comprehensive revision of the rules protecting the island chain’s delicate waters.

Made available to the public on the morning of Dec. 13, the document marks the culmination of more than a decade of work by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) staff and stakeholder partners, beginning in 2011 with a troubling condition report signaling the decline of several elements throughout the sanctuary.

Robust public comment periods with more than 80,000 submissions throughout 2019 and 2022, followed by a review period by a litany of enforcement, management and advisory agencies, have led to the final rule set to be published in mid-January. From there, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis will have 45 days to review the proposed regulations with, as former Sanctuary Superintendent Sarah Fangman put it, “a sledgehammer or scalpel,” deciding whether to accept or reject them in full, or veto individual items affecting state waters.

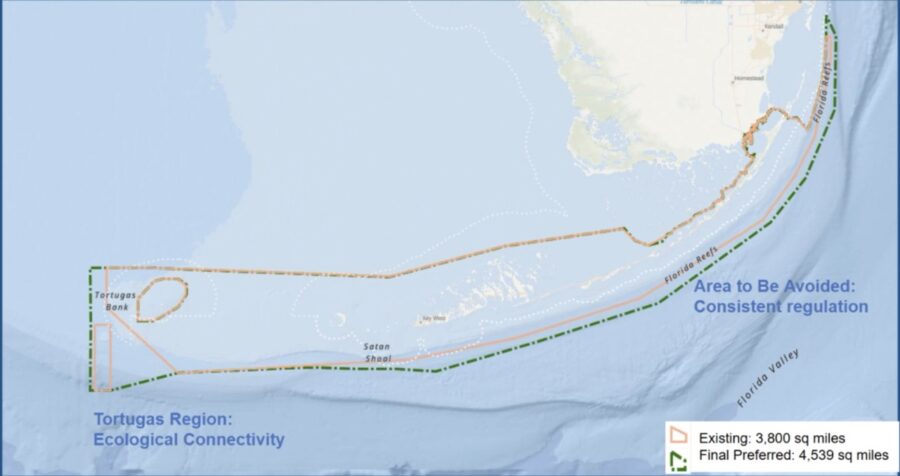

A presentation from FKNMS policy analyst Beth Dieveney to the virtually-gathered FKNMS Sanctuary Advisory Council (SAC) on Dec. 13 outlined major talking points of the final rule, including a plan to expand sanctuary boundaries by roughly 20% – primarily extending the area’s Atlantic edge and pushing south and west beyond the Dry Tortugas.

A sanctuary expansion to include Pulley Ridge, considered in the most recent Restoration Blueprint draft in order to implement a no-anchor area, is not a component of the final rule, as the no-anchor provision was already implemented by the International Maritime Organization in June 2023, Dieveney said.

Recent crises demanding rapid responses, such as the 2023 heat wave that triggered mass coral bleaching throughout the Keys, have shaped updated emergency regulation procedures, allowing temporary regulations in designated categories to remain in place for 180 days with an additional 186-day extension.

Cruise ships will be prohibited from all discharges other than cooling water within sanctuary boundaries, and attracting or feeding fish, including sharks, from boats or while diving, will be banned. Dieveney said sanctuary officials would “consider” grandfathering in existing eco-tour and fish-feeding operations, but that the rule won’t apply to traditional uses of chum and bait while fishing.

Boats entering Sanctuary Preservation Areas, restoration areas and conservation areas are prohibited from anchoring and will be required to use mooring buoys provided by NOAA after a two-year planning and installation period, with special large-vessel buoys required for vessels from 65 to 100 feet.

Sanctuary Preservation Areas at French Reef off Key Largo and Rock Key off Key West will be eliminated, while two new zones will protect patch reefs at Turtle Rocks in the Upper Keys and Turtle Shoals in the Middle Keys. Zones at Key Largo Dry Rocks and Grecian Rocks will be combined, while zones at Carysfort Reef, Alligator Reef and Sombrero Key will have their boundaries modified to protect reef habitats. Fifteen Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs), established to protect nearshore habitats and specific species, will undergo sizing or regulatory changes, some with reductions to provide greater access following public comment, and 20 new WMAs will be added.

Exceptions for catch-and-release fishing inside SPAs will be eliminated, and sanctuary officials will stop issuing bait fish permits over the next three years, Dieveney said.

The final rule will also include designated habitat restoration areas undergoing active coral restoration, protected by a 200-yard buffer, and 11 designated coral nursery restoration areas to protect underwater nursery structures and their corals.

“No one got everything, but everyone got something,” Matt Brookhart, NOAA’s eastern regional director for national marine sanctuaries, told the council. “We think we’ve landed in the Goldilocks zone of ‘just right,’ balancing a range of voices.”

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration or stress to say that this has probably been the most collaborative process in the history of the Florida Keys,” John Armor, NOAA’s director of national marine sanctuaries, told the Weekly by phone Friday morning.

“From improving water quality to collaborating on an artificial reef pilot program, Monroe County has made great strides and investments in partnership with FWC and NOAA,” said Monroe County Commissioner Holly Raschein said in a press release. “I’m excited to see the Restoration Blueprint reach the finish line, and look forward to working with all the agencies and our residents to fight for the Keys’ future for years to come.”

FWC tension carries over

While Friday’s reveal was met with near-universal celebration from council members, questions posed to sanctuary officials immediately raised the subject of regulatory concerns voiced by FWC officials this fall.

A letter sent from FWC chairman Rodney Barreto to newly-installed Sanctuary Superintendent Matt Stout on Nov. 5 took aim at a change to regulatory language within the Restoration Blueprint, criticizing a provision that would only allow the Florida governor to veto fisheries regulations in state waters.

“While FKNMS has consistently stated that it does not intend to circumvent FWC’s authority over fisheries regulations in state waters … (this change) is contrary to how fisheries regulatory authority is set up in the State of Florida,” Barreto wrote.

The letter went on to list 10 “essential” remaining items of disagreement between FWC and sanctuary officials, including: allowance of drift fishing and trolling operations in certain Sanctuary Preservation and Conservation Areas, continued allowance of catch-and-release fishing by trolling in other SPAs, continued issuance of bait fishing permits and support for Monroe County’s newly-developed Habitat Support Plan and installation of artificial reefs.

However, as noted by charter captain Greg Eklund, none of the targeted items had been changed in the final rule. Both Stout and SAC Chair Ben Daughtry attributed the omission to the timing of the letter in relation to the environmental impact statement’s issuance, but pledged to meet with state officials the following week to work through outstanding issues.

“It seems to me like there’s some issues between the state and the sanctuary that really should have been worked out before this was released,” Eklund replied.

Further pushed on whether he believed sanctuary and state officials could find common ground on fishing regulations inside SPAs and baitfish permits, Stout replied that “the federal statute we have to follow requires that we manage for conservation.”

“We do take the input, of course, of our state partners and all of our partners and users in the management,” he added. “But when the facts show that we have a primary purpose of conservation, those are the actions we do take.”

“I hear what you’re saying about how the (environmental impact statement) was already kind of put in play relative to when you received the letter,” said FWC federal fisheries section leader CJ Sweetman. “But this information has been common knowledge in working with our sanctuary partners throughout the entire process. So nothing in that letter should have been a surprise in any capacity.”

Adaptive management is key

While applauding Friday’s milestone, sanctuary staff and advisory members continually stressed a theme of adaptive management for marine regulations moving forward.

Before her departure, Fangman openly admitted to the council that while the Restoration Blueprint represents a massive leap forward for conservation, a comprehensive Keyswide overhaul of sanctuary regulations, requiring more than a decade of refinement and review, was trying to “do too much at once.”

Armor and Stout reiterated those concerns Friday morning, reinforcing the need for working groups that could provide timely and targeted responses to ever-changing issues within the sanctuary.

“We have to have systems in place where we can work to adapt in close to real time,” Armor said, praising the precedent set by NOAA, FWC and other partners in responding to 2023’s coral bleaching epidemic. “That’s kind of a model that I think we need to start doing better at. That’s a much more discrete, focused process that we were able to get through quickly.”

“I think that’s a great way to be more nimble and responsive, and show that we can work collaboratively on all the issues that face us here in the Florida Keys,” Stout said.