Massive offshore weedlines are the stuff of Keys bluewater anglers’ dreams. But though it’s too early to say for sure, the latest mass approaching the island chain is one they might wish went elsewhere.

By now, most have heard about the massive “blob” of sargassum – an umbrella term for hundreds of species of brown algae – approaching the Keys. Stretching nearly all the way across the Atlantic Ocean, with an estimated current mass of 13 million tons, it may undoubtedly prove problematic for the Keys in the coming months, as it has done most notably in the summers of 2018 and 2022.

But regardless of the picture painted by other reports, according to those who study the macroalgae, it doesn’t mean that thousands of miles of weeds are about to wash up on Keys beaches all at once. And it’s still too early to predict the final picture for the island chain when all is said and done.

This week, Keys Weekly was fortunate to sit down with renowned Florida Atlantic University researcher Brian Lapointe and Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary research coordinator Andy Bruckner to better understand what’s driving the algae, and what the Keys can expect from here.

What is “the blob?”

First things first: This isn’t a one-time traveling mass that appeared out of nowhere, and it’s entirely separate from red tide, although the two can cause similar effects.

The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is the world’s largest recurring macroalgae bloom, often extending from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico across the southern edge of the Sargasso Sea. With air bladders that help it stay afloat and a rough, intertwining shape that helps keep large patches together, the massive floating habitat is a hotspot for biodiversity. In addition to providing vital food and protection for fish, mammals, marine birds, turtles, crabs and more, it serves as a nursery for mahi mahi and jack species.

The belt’s annual bloom usually begins in the winter and spring months, typically peaking in early to mid summer. Its distribution throughout the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea is largely driven by currents and ocean circulation.

“The ‘blob’ moves into the Caribbean … and some of that is carried up into the Gulf, and some of it is carried by the Gulf Stream around past the Tortugas along the Florida Keys up to Miami,” Bruckner said.

What’s the issue?

While the floating version of sargassum provides a critical offshore habitat, piles of the algae on beaches and in nearshore waters can prove problematic.

“Dead zones” can replace vital nurseries as large quantities of sargassum create anoxic conditions that threaten marine life. In shallow water, degrading algae masses can kill plants and animals on the seafloor, while hydrogen sulfide gas released by the decomposing organism is a toxic eye and respiratory irritant. As if that wasn’t enough, it smells like rotten eggs, an unwelcome scent for the throngs of tourists who frequent Florida’s beaches each year.

“The biggest thing is that if there is a lot of this material that comes into the shoreline, there should be recommendations that people aren’t swimming in that water,” said Bruckner.

Unfortunately, disposing of the piles of smelly sargassum when it washes ashore isn’t as simple as scooping it all up and using it for fertilizer.

With such a high arsenic content, the macroalgae can’t safely supplement any plant intended for human consumption.

How did we get here?

Lapointe has studied sargassum since the 1980s, but he said that as he analyzed tissue from algae in the belt in more recent years, one nutrient in particular stood out.

“I was analyzing data from the 1980s that I collected. … In comparing those numbers with post-2010 data, that’s where we see nitrogen levels going up 35%, and the nitrogen:phospate ratio went up by 111%. That was my eureka moment,” he told the Weekly. “This sargassum looks like it’s being fed by the major rivers like the Amazon, the Orinoco, the Congo and the Mississippi.

“It just so happens that the nitrogen and phosphorus contents are highest in the winter and spring, just when the rivers are discharging the most. … By summertime, those river discharges are actually going down, and that’s when the growth slows down as tissues become depleted of nitrogen and phosphorus.”

Over the past 12 years, a formerly limiting nutrient to the growth and biomass of the belt ceased to be a handcuff, as human population growth fueled high reactive nitrogen levels with wastewater, fertilizers, deforestation and other contributors, Lapointe said. The belt is capable of doubling its size in anywhere from two to four weeks under ideal conditions, and with the algae continuing to exhaust the amount of available phosphorus, another critical nutrient, it turns to a chemical analog: arsenate, a salt of arsenic acid.

Adding further fuel to the fire are rising sea temperatures.

“The winter temperatures are anywhere between two to six degrees higher than what we’d typically see at this time of year,” said Bruckner. “We’ve now shifted to an El Nino event … (and) because it’s already warmer than it should be this year, that could help fuel the growth.”

Where are we now?

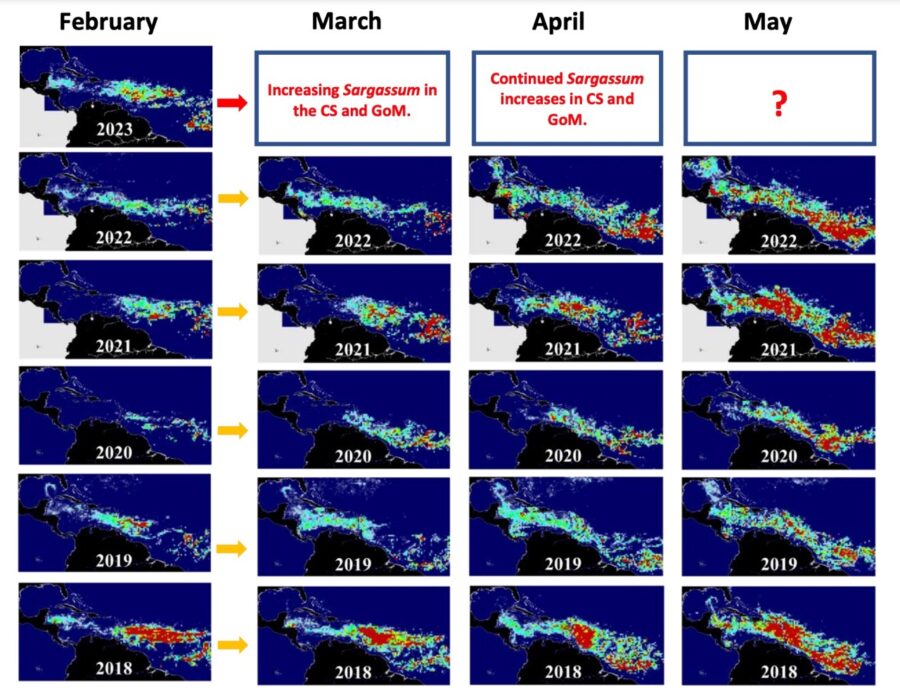

Researchers began actively tracking the size of the belt with multiple methods, including satellite imagery, during the first bloom in 2011. Since then, the 2018 bloom has been the record-setting standard, with 2022 as another severe event.

Thus far in 2023, the blob had an early start to its annual growth. But the final impact is yet to be seen. A sargassum outlook summary published by the University of South Florida’s Optical Oceanography Lab noted that “although the overall sargassum quantity in the central Atlantic Ocean decreased from January to February … this abundance (6.1 million tons) is still the second-highest amount recorded for the month of February. … (And) within the Caribbean Sea, sargassum quantity nearly doubled.

“The decrease in sargassum quantity from January to February is uncommon, and presents a glimmer of hope that the overall 2023 bloom may not be as large as previously feared, although 2023 will still be a major sargassum year,” the outlook concludes.

Though beaches throughout South Florida are already starting to see sargassum arriving as March gives way to April, Bruckner said it’s too early to define the severity of this year’s event.

“One of the fears, I think, is that it’s a little earlier than normal,” he said. “And, you know, there is the potential for it to get much, much worse than it is, but it’s sort of hard to predict that.”

Where do we go from here?

With sargassum research a growing priority over the last decade, further work using satellites to track fine-scale current data should prove crucial in accurately predicting movements of algae within the belt.

Physical barriers and collection apparatuses are important pieces of the puzzle to combat large accumulations of the algae on shore, but with the belt affecting so many diverse areas, there’s no single defense method that’s perfect for all.

One possible solution may rest with SOS Carbon, a spinoff organization from the mechanical engineering department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that engineers solutions for sargassum collection and disposal. A net-based Littoral Collection Module developed by the organization can continuously collect the algae, while a second Sargassum Ocean Sequestration of Carbon process periodically sinks large collections of sargassum to depths that collapse its air bladders, preventing it from resurfacing and continuing to absorb buoyant nutrient plumes from rivers. As Lapointe noted, such a process would also chip away at environmental carbon dioxide levels by sending CO2 absorbed by the macroalgae to the ocean floor for years.

For a health briefing on sargassum produced by the Florida Department of Health, visit https://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/beach-water-quality/_documents/sargassum-factsheet-appr-final.pdf.

To visit USF’s live sargassum watch system, including an interactive map, visit https://optics.marine.usf.edu/projects/saws.html.