Editor’s note: This is the third in a four-part series on Dr. Henry Perrine. Read the first two at keysweekly.com.

Dr. Henry Perrine’s 10-year post as U.S. consul at Tabasco, Mexico, ended in 1837. Because he had followed President John Quincy Adams’ directive regarding the study of local flora and had worked to establish two tropical plant nurseries in the Florida Territory, sub-tropical South Florida was to become his new home.

After sailing away from the Yucatan Peninsula, the doctor visited Key West. During his one-month stay, he met Judge James Webb, who joined Perrine and Charles Howe of Indian Key, as partners in the Tropical Plant Company. In letters, Perrine revealed Webb “was the only reputable resident, whose character and condition combined the circumstance essential for a co-trustee of any tropical plant company.” It would not be his last jab at the people of Key West.

Perrine returned to his family in New York. Due to the second escalation of the Seminole War, escalations that included an attack on the Cape Florida Lighthouse in 1836, Joseph R. Poinsett, Secretary of the Navy and a friend of Perrine’s, advised against his return to the Florida Territory. Poinsett wrote to the doctor, “The war had again broken out and it would not be prudent to go onto the land.”

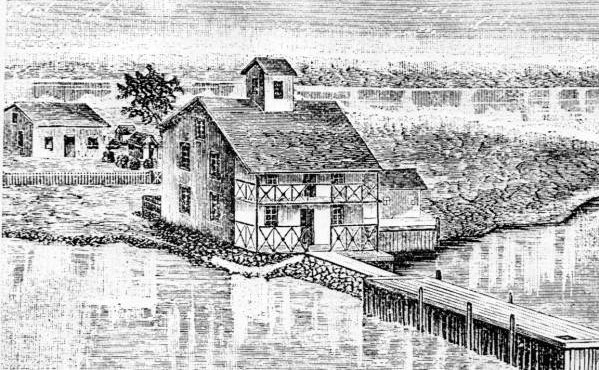

Perrine insisted. Eager to move closer to his plants, Indian Key seemed, to him, far enough away from the hostilities. When the Perrine family arrived on Christmas Day 1838, they stayed in a house owned by Charles Howe. James Egan built the two-and-a-half-story home in 1832. By April, Egan’s building was advertised in Key West as a boarding house promising to “Render satisfaction to those who may favor him with their company.” Egan would sell the house to Jacob Housman. Housman, in turn, sold it to Charles Howe, who lived in a large, single-story house close by.

In a letter to the editor of “The Farmer’s Register” dated April 23, 1839, Perrine discussed Morus multicaulis, the mulberry tree. Native to China and India, the leaves of the Morus alba, the white mulberry, are the silkworm’s primary food source. The mulberry, introduced to Mexico, was one of some 72 species Perrine shipped to the United States.

In 1833, Perrine sent a dozen mulberry trees to John Dubose, keeper at the Cape Florida Lighthouse. The trees thrived and survived the 1835 hurricane. Using his connections with Poinsett, the mulberry trees were to be dug up and returned to Perrine. Navy lieutenants Shubrick and Coste were assigned the task of delivering the trees. Neither officer fulfilled his duty.

According to a letter written by Dr. Perrine, Shubrick and his team pulled several large mulberry trees and planted them at Soldier Key, one of the nearly 50 islands located north of Key Largo. Lt. Coste, too, retrieved several mature mulberry trees at Cape Florida and sailed with them, not to Indian Key and the Tropical Plant Company, but to the nearby Tea Table Key. Perrine wrote, “Be it understood Lieut. Coste occupies and claims this Key as his own, from the fact that since September last, he has been clearing it, improving it, and building on it, with governmental means of men and materials; that he is converting said Tea-Table Key into a town-site for a rival port of Indian Key, under the apparent patronage of the inimical proprietors and public offices of Key West; and that hence, not content with speculating in town lots, he is determined to speculate also in tropical plants by the abuse of the same governmental means.”

By 1838, Key Vaca, more easily recognized as the heart of Marathon today, became home to a community of some 200 people. Known as Conchtown, it consisted of about 50 homes with half of the buildings constructed of wood and half with palmetto thatch. There was also a small school. When Perrine visited, he introduced the community to both the mulberry and Sea Island cotton. The cotton had already been growing on the islands. Perrine wrote, “these two precious staples will be able to afford ample funds for schools and churches.”

According to Perrine, the people of Key West referred to this group as “lazy konks.” According to Dr. Perrine, “I am now fully satisfied that our agricultural statesman would promptly pronounce that the humblest grower of sweet potatoes at Key Vacas is an infinitely more useful citizen of South Florida than the haughtiest of office-holder in Key West.”

Next week: In the last of this four-part series, Perrine’s decision to venture to Indian Key will prove disastrous. Evidence will also argue against the idea that, of the approximately 72 species of plants Perrine introduced to the United States, the Key lime was not one of them.