#1 How we got to this point (Sept. 27, 2018)

#2 The hurricane evacuation model’s influence on development (Sept. 20, 2018)

#3 What the ‘takings’ lawsuit might look like (Oct. 4, 2018)

#4 Options to detour chaos (Oct. 11, 2018)

#5 In conclusion … (Oct. 18, 2018)

By Frank Greenman & Sara Matthis

In a little more than five years, new development will come to a grinding halt in the Florida Keys. At least, that is what the State of Florida has decreed for the islands it has designated an “Area of Critical Concern.” Beginning in 2023, it will no longer issue new building permits for Keys municipalities. None. Zilch. Zip. Nada. If this comes to pass, what happens next? Will landowners sue because the state (and local governments) is gutting the value of their investment by preventing them from building their dream home on their vacant lot? Will that raise taxes? What will happen to real estate values? Will builders be out of business? The ramifications are wide and far-reaching. The future starts now.

Back in 1972, Florida initiated a statewide planning and growth management law that required each county to create a “Comprehensive Plan” for land use management and to accommodate the fast population growth Florida was experiencing.

In the 1960s and 70s, the Florida Keys had become infamous for rampant drug smuggling and ineffective government. Local Keys government appeared to accommodate both smuggling and unrestrained development. One of the issues that brought the development issue to state attention was a 1972 plan to build three high-rise apartment buildings in Marathon, that led to a well-publicized campaign for “No high-rise in the Keys.” As a result of the public outcry, only one tower was built (Bonefish Towers) but development in the Keys was now on the state’s radar. Because of the Keys’ unique environment, and the risk to America’s only living reef, environmental organizations such as Friends of the Everglades, 1000 Friends of Florida and local activists such as George and Mary Barley in Islamorada lobbied the state to do more to protect the Keys from overdevelopment and inadequate governance.

In response, in 1974, the state decreed the Florida Keys an “Area of Critical Concern.” (Key West’s separate Area of Critical Concern designation would come later.) In 1979, the state passed “Principles for Guiding Development” for the Florida Keys. The state took over the heretofore local responsibility for land management and development oversight. In real effect, all development in the Keys would be run by the state until the state had confidence that local governments could be trusted to protect the valuable resource of the Keys. That lack of confidence was not misplaced. Back in the 1980s the City of Key West was dumping 6 million gallons of raw sewage into the ocean every day. In 1980, Monroe County approved Port Bougainville – a 2,800-unit development on 406 acres in the Upper Keys.

In 1982, a countywide election put new progressive leaders in the judiciary, state attorney, public defender, and county commission. A proposed comprehensive plan was presented at public hearing throughout the Keys, and in 1986 a new county commission passed the county’s first Comprehensive Plan and Land Use Regulations.

The plan evolved over 88 meetings — every single one of them attended by Ed Swift, then a 31-year-old newly elected county commissioner appointed as liaison.

“I’m not sure why the hell that happened,” said Swift. The gargantuan task was accompanied by much opposition, including that of former state Rep. Joe Allen who encouraged Keys residents to fight back against the state. Tensions were high at the meetings, and a report in a 1986 issue of Florida Trend magazine mentioned an audience member at a public hearing tried to attack a speaker with a knife.

“I don’t remember that,” Swift said, “but I was at plenty of meetings where people shook their fists and shouted.”

In 1983, Charles Pattison was a Keys field agent for the state Department of Community Affairs, charged with overseeing Keys development. (He is now director of Monroe County Land Authority.)

“The early days were contentious. Anything the county did had to be approved by DCA,” he said.

The state and the county began cooperating in land use decisions, and the state slowly transferred more responsibility to local government but retained overall control over development in the Keys. For example, in order to build, a developer must meet a number of state-mandated requirements regarding open space, size of the building, etc. However, the state Department of Economic Opportunity must still approve changes to the comprehensive plan. (Under Gov. Rick Scott, the Department of Community Affairs morphed into the Department of Economic Opportunity.)

In 1992, the state required the county commission to pass a Rate of Growth Ordinance (ROGO), which severely limited the number of buildings to be built in the Keys. No further development permits would be allowed. This restriction was based on the state’s evaluation of the limited resources available within the Keys, and most importantly, the state’s determination that the restrictions imposed by ROGO would allow all residents of the Keys to evacuate within 24 hours in the event of a major hurricane. That evacuation model has been the primary rationale for restricting growth in the Florida Keys.

But why 2023? How did we arrive at that expiration date? Well, in 2012, the state and Keys municipalities came together to determine how many more building rights could be given out before the hurricane evacuation model reached “capacity.” At that meeting, it was determined that there was “one hour” of evacuation time left, or equal to the time it would take an extra 3,550 households to evacuate. The 3,550 permits were split among the county (with the lion’s share), Key West, Islamorada, Marathon, etc. The entities then identified a rate at which they would dole out the building allocations … which brings us to 2023.

There is no firm count on how many lots are still undeveloped in the Keys. Some put the number at about 3,500, others as high as 10,000. The concern is that in 2023, there will be many, many property owners suing the county and the cities for compensation for the “taking” of their right to develop their property. At today’s property values, such a liability is far beyond the local governments’ ability to pay. That threat is perceived as a financial Armageddon by Keys governments.

“Back in the ’80s I think we estimated that it would cost $1 billion [to purchase the lots without allocations] that would be paid by the federal, state and local governments. It was too big a number to focus on. But looking back, and seeing what happened with sewage treatment, it could have been possible,” said Pattison, referring to the high cost of sewering the Keys.

In the mid-’80s, the Keys became a guinea pig of growth management, required to come up with a growth management plan long before it was required of other counties. Now, in 2023, the Keys will once again be first to test the “no new development” waters.

— Frank Greenman is a retired general land use attorney living in the Florida Keys. He practiced for 38 years, as well as was one of the first councilmen elected to the City of Marathon, established in 1999. Sara Matthis is the editor of the Weekly Newspapers.

Please send your thoughts and comments about this issue to sara@keysweekly.com. Comments will be gathered and published, as space permits, with the author’s name and hometown. All of the articles will be available at keysweekly.com as they publish.

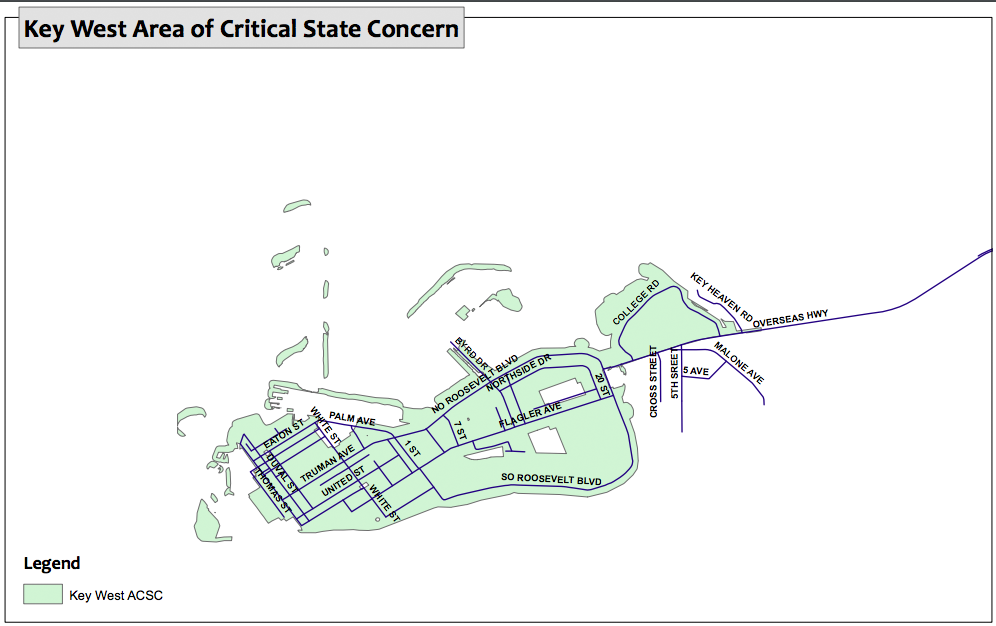

Locals are very used to living in an “Area of Critical Concern” — it’s as normal as sliced bread. But there are only five such areas in Florida — City of Apalachicola, City of Key West and the Florida Keys (counted separately), The Green Swamp, and The Big Cypress Swamp. In Apalachicola, the area measures about 12 city blocks by 13 city blocks. The Green Swamp and Big Cypress Swamps are very sparsely populated. While there are environmental stipulations that come with this designation, it only has one purpose: “to guide local government growth and development decisions related to local comprehensive plans and land development regulations.”