What was ideal was heavy rain that happened the night before, the kind of inclement weather that tends to encourage migrating birds to maybe take a break and ride things out down here, among the lowly terrestrials, at least until the storms move out of the way.

What was not ideal was it being the second week in May, kind of late in the migration, when most birds had already passed over and through and on up into North America.

It seemed worth the two-mile trip to Fort Zach, though, to see if there was any fallout.

The last time I’d been in the park, a week-and-a-half before, I’d sat at the edge of the moat with my friend Ellen Westbrook, and then my friend Lisa Morehouse, and watched as a steady parade of warblers came in to bathe on the low twigs that dipped into the water.

Warblers tend to be the bulk and the color guard of the migration. We’ve recorded close to 40 species of them in the Keys. And they are pretty fun birds to see, small things, often brightly colored, sometimes just interestingly colored, slightly larger than winged baby carrots, that spin and flit through the trees.

So I went back to the same spot, sat down in the dirt and hoped for a repeat, which is never the right hope in birdwatching.

Instead of a parade of small songbirds, there was one very large and very dark – almost black – iguana. And above him, a small concert of noisy local red-winged blackbirds.

Somewhere high in the canopy behind me I heard a soft tuk-tuk-tuk, the contact call of a yellow-billed cuckoo. I didn’t bother to turn around and look for it because cuckoos, especially cuckoos in migration, tend to be lurkers, always three or four layers deep in foliage, always heading toward the exit before you even notice them.

I got up and began to wander.

There wasn’t the level of bird activity I’d hoped for, but I could see the occasional shadow move through the trees. More cuckoos, I suspected, but nothing distinct in color or shape.

My binoculars are a well-used, nearly 20-year-old pair of Swarovskis. (Apparently they make jewelry, too?) I accidentally dropped them in a bag from a foot or two onto our tile floor a while back, and didn’t think about it until a few days later, when I went to use them and realized the right barrel no longer focused.

As with any well-used tool that you’ve had for so long, the binoculars become like an extension of the user. You lift them to your eyes and you find the bird, or whatever you were looking for, without thinking about it.

I didn’t realize how much being able to focus only one eye would stymie me. I’d see some movement, lift the binoculars, and the blurry side would somehow completely scramble the sharp side. When I would remember to close one eye, somehow my aim was all off. (I could fix all this if I just remembered to ship them off for repair.)

My suspicions about the yellow-billed cuckoos were confirmed without binoculars up behind the blacksmith shop at the park, when I stepped on a twig and three of them leapt out of the tree and flew off in different directions.

It was all silhouette, but cuckoos have a distinct shape. To me they always look a little hunched when they fly, curving downward, as if, while in the open air, they are conveying with their body language just how much they would like to return to some form of cover.

I did see a closely related and similarly shaped black-billed cuckoo in the park once, and the elusive mangrove cuckoo has been seen there, though not by me. But seeing a lot of cuckoos in the park made it more likely that I was encountering a wave of migrating yellow-bills.

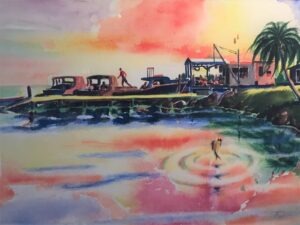

Yellow-billed cuckoos breed in the Keys, as well as in most of the eastern half of North America. They breed in the western half of the continent, too, but their numbers there crashed heavily in the 1900s. And for some reason, in my experience, the local breeders, which will be easier to find in the coming weeks, are much less skittish than the migrants. (The photo here is from a Keys breeder.)

Most of our cultural notions about cuckoos comes from Europe, where in the mid-1600s Swiss clock makers figured out how to mimic the sound mechanically, and make some very memorable clocks. And European cuckoos have been equated with craziness since the time of Aristophanes in the fifth century B.C.

For a long time I mistakenly thought that New World cuckoos, like a lot of New World bird names given by European immigrants, shared a name with the Old World cuckoos, though not a twig on the taxonomic tree. But I was wrong. The common cuckoo, which inspired the clocks, and the yellow-billed cuckoo (as well as the black-billed and the mangrove) are actually in the same family.

Besides being known as metaphors for madness, cuckoos in Europe are also thought to be some of nature’s more devious villains, at least in an anthropomorphic sense. This is most likely due to their habits of nest parasitism, meaning they don’t build nests of their own, but instead lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. Cuckoo chicks mature faster, allowing them to muscle in on the best food from the duped host parents, and to thrive at the expense of the actual offspring. The chicks also have a small bare patch on their rump that allows them to slow-motion twerk the eggs of their host parents up and over the side of the nest.

Yellow-billed cuckoos actually build their own nests, and both parents share near equal responsibility for the brooding and feeding of their own chicks. But they do also, on occasion, lay eggs in the nests of American robins, gray catbirds, wood thrushes and at least eight other species of North American songbirds.

This is likely why American robins, gray catbirds and wood thrushes will sometimes go after yellow-billed cuckoos when they see them. And also possibly why yellow-billed cuckoos are so likely to avoid attention and loiter in the shadows.