Holidays in the Keys tend to be a mix of traditional and tropical, with Santas in Hawaiian shirts, boat parades for the Fourth of July and SCUBA diving for Easter eggs on the Vandenberg Wreck. Halloween is no different.

Hanna Koch, a visiting scientist at Mote’s International Center for Coral Reef Research and Restoration (IC2R3) facility, and Cody Engelsma, a coral reproduction technician, showcased their three favorite “spooky” corals, while explaining a little bit of the science behind their quirky Halloween spirit:

- Zombie Corals

Zombies, a Halloween favorite, are the undead. They can walk and sometimes even talk, but they are not normal. And, you certainly couldn’t date one. Zombie corals, it turns out, are a real thing and quite similar to their unhuman counterparts.

If you remember Keys Weekly’s article from Oct. 24 on coral reproduction, Koch and her team reminded us that coral sexual reproduction is critical for the survival of the reef. Coral sexual maturity in many species is size-, not age-, dependent. Therefore, a large healthy-looking coral that should be sexually reproducing but isn’t is called a “zombie.”

Researchers around the world have noticed these freaky reproductive fakes and are working to explain why. “Chemical toxicity — some researchers believe it’s a result of developmental or reproductive toxicity attributed to chemical pollutants, like what you might find in sunscreen,” said Koch. These chemicals are endocrine disruptors, meaning they throw hormones and sometimes reproductive development or cycles out of sync. Koch adds, “It has been shown that reefs that are heavily visited by tourists also have a higher level of chemical pollutants, so there might be a connection between human activity, local chemical pollution in the water, and failed coral reproductive activity.”

Koch and her team have similarly observed some 3-year-old restored staghorn corals that aren’t sexually mature, despite being well beyond the size for sexual maturity. “These corals sit in a SPA, so it’s open to divers, snorkelers and tourists,” says Koch. “It all goes back to how we humans impact our environment in so many ways we don’t even see.”

- Coral Fluorescence

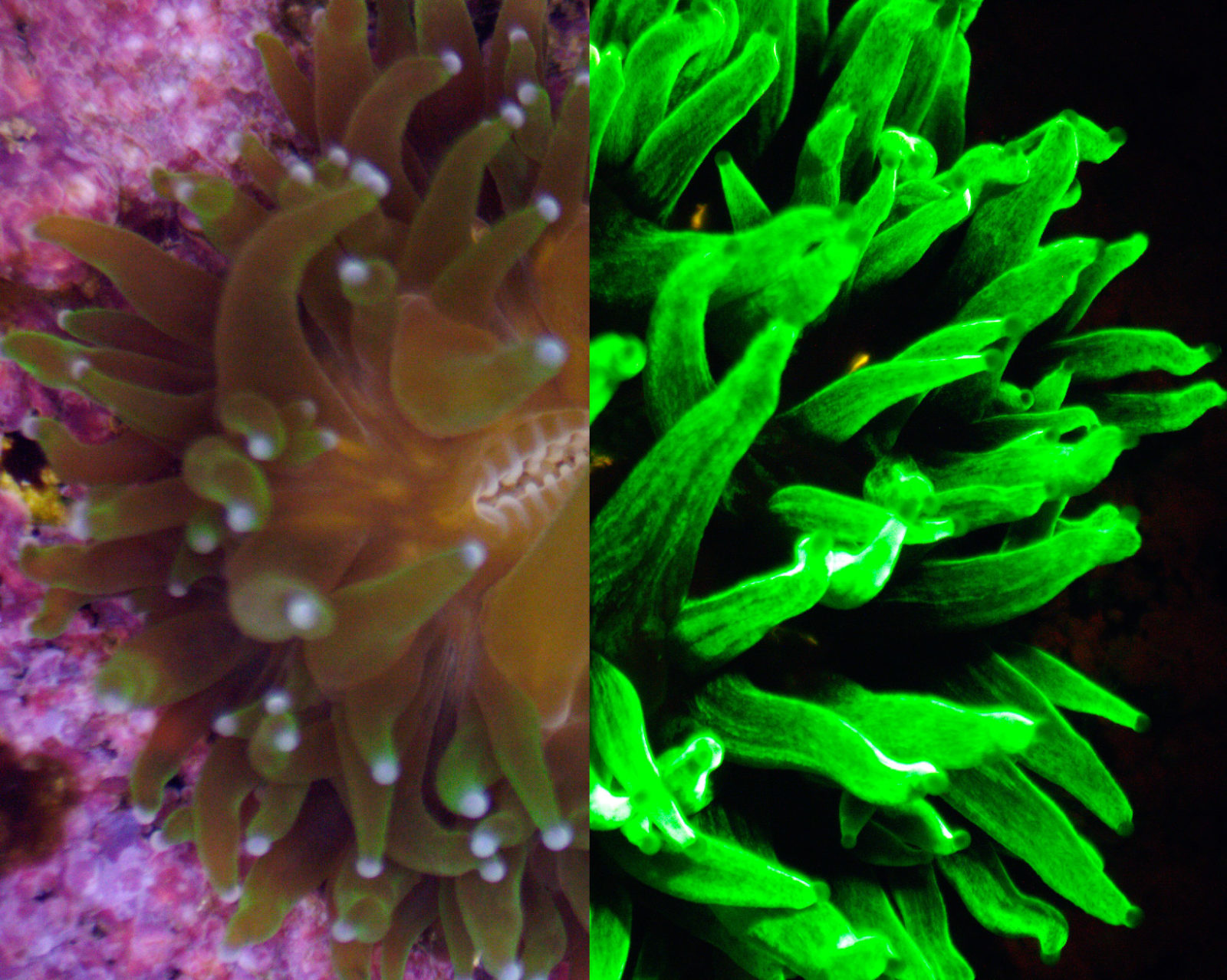

What’s Halloween without some glow-in-the-dark fun? Many corals, it turns out, glow all the time, we just can’t see it with our naked eyes. Back at Mote, Engelsma adds a blue light adaptor onto his stereoscope and shows us a whole new glowing world of corals under the magnifying glass.

It’s called “coral fluorescence,” and it happens when corals absorb light in one wavelength but emit it at another. The process leads to color change at the longer emitted wavelength, which looks like a “glow.” The blue filter just allows us to see this “glow.” Koch adds, “The first time we saw it, we were geeking out!”

Natural coral fluorescence is still being studied, but there are several ideas for the functions it might serve. In deep water corals, it likely plays some role in photosynthesis and energy production. Corals have symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae within their tissues that uses sunlight to photosynthesize and produce energy for the coral. Within the corals, blue light converts to orange, which is more efficiently utilized by the zooxanthellae for energy production.

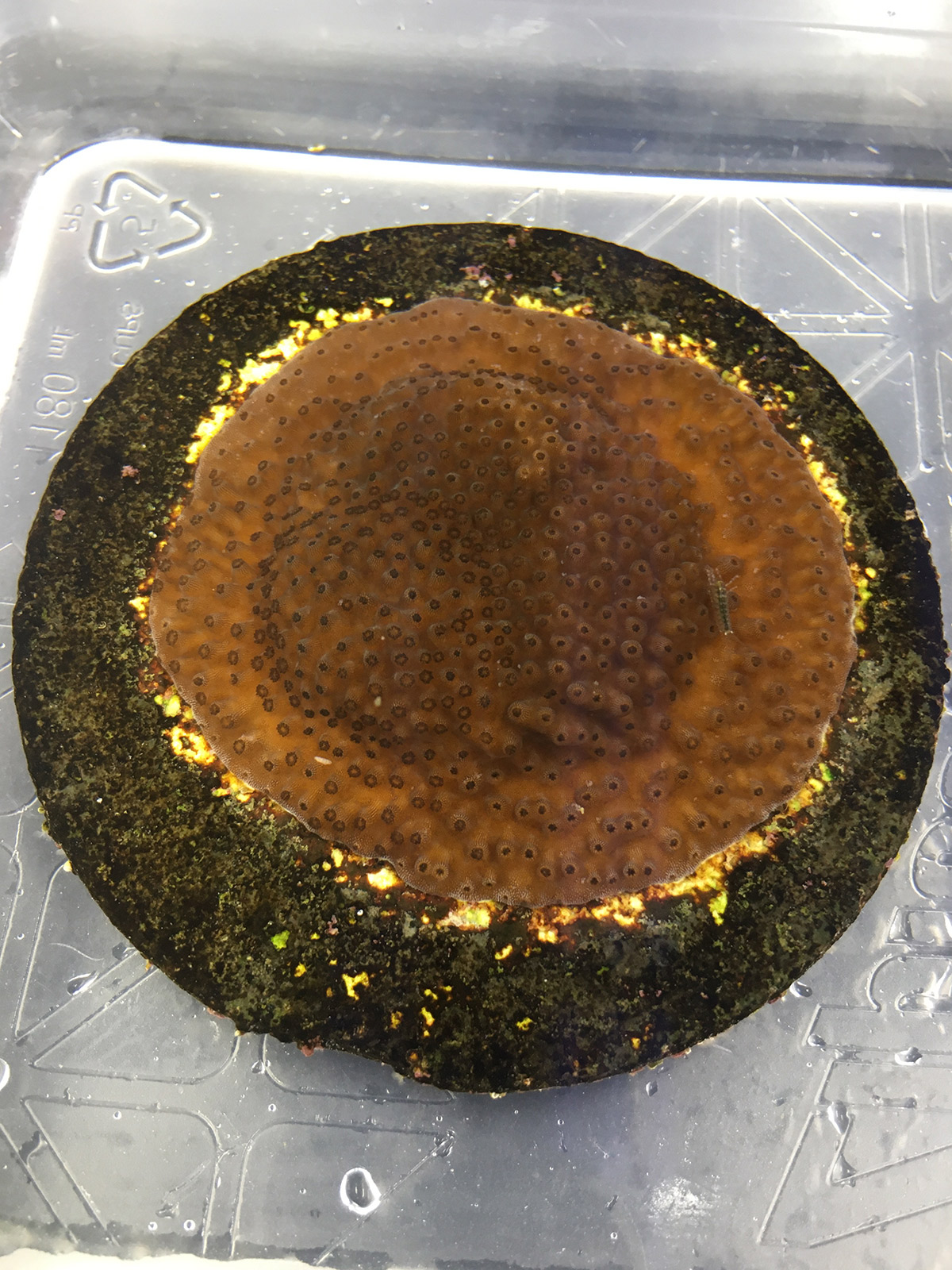

Engelsma shows a close-up of an Orbicella faveolata coral, more commonly known as mountainous star coral. He points out bright, glowing tips and a circular center. “Look at the tentacles and the polyp’s mouth,” he says. “The concentration of fluorescence there indicates it might be used to attract and capture prey.”

Koch describes one further function the cool glow might serve: as a natural sunscreen. “There have been observations that compromised or injured corals fluoresce more,” she says. “They might express these molecules to protect against toxic oxygen radicals that can lead to tissue damage from harmful UV rays.” It may be that the cool glow serves multiple functions that scientists are just beginning to uncover.

- Chimeras

Finally, Halloween would be incomplete without monsters. There are plenty of horror films out there where mad scientists fuse together body parts or combine people to create bionic villains, Frankenstein monsters, human caterpillars and everything in-between.

While corals don’t take it to that extreme, the Mote scientists have observed chimeras within their coral tanks. Chimeras are genetically distinct individuals who fuse together and become one. “You can think of them as siblings, same parents but different individuals,” explains Koch. “They’re from the same fertilization batch but were individual larvae before fusing to become a single colony.”

Koch and Engelsma observed several coral “siblings” attaching together and living as one organism. “Perhaps they decided to fuse for stress-tolerance,” explains Koch. The fused corals live as one unit, leveraging the strengths of both individuals, accounting for the weaknesses and sharing resources. While some scientists may think chimeras don’t have a significant purpose, Koch and Engelsma hope to conduct further experiments on their mashed-up monsters to explore how far the shared adaptations will go. “Who knows, maybe this will show us how corals can further adapt to a changing future environment,” says Koch.