Housing is the largest single challenge facing Florida Keys residents and has been for decades. With scarce buildable land, strict height restrictions, sky-high property values, second homes that sit empty most of the year and a proliferation of vacation rentals, many full-time workers no longer can afford to live or rent in the island chain, much less buy a home.

Last week, Keys Weekly defined the housing problem. This week, we examine what caused it, and how we got here. A complex blend of contributing factors has turned the Florida Keys’ longtime housing concerns into an undeniable crisis. In hours of conversations with government officials, attorneys, real estate agents, lenders and citizens closely interwoven with the issue, the following factors never failed to surface:

IT STARTS WITH THE STATE

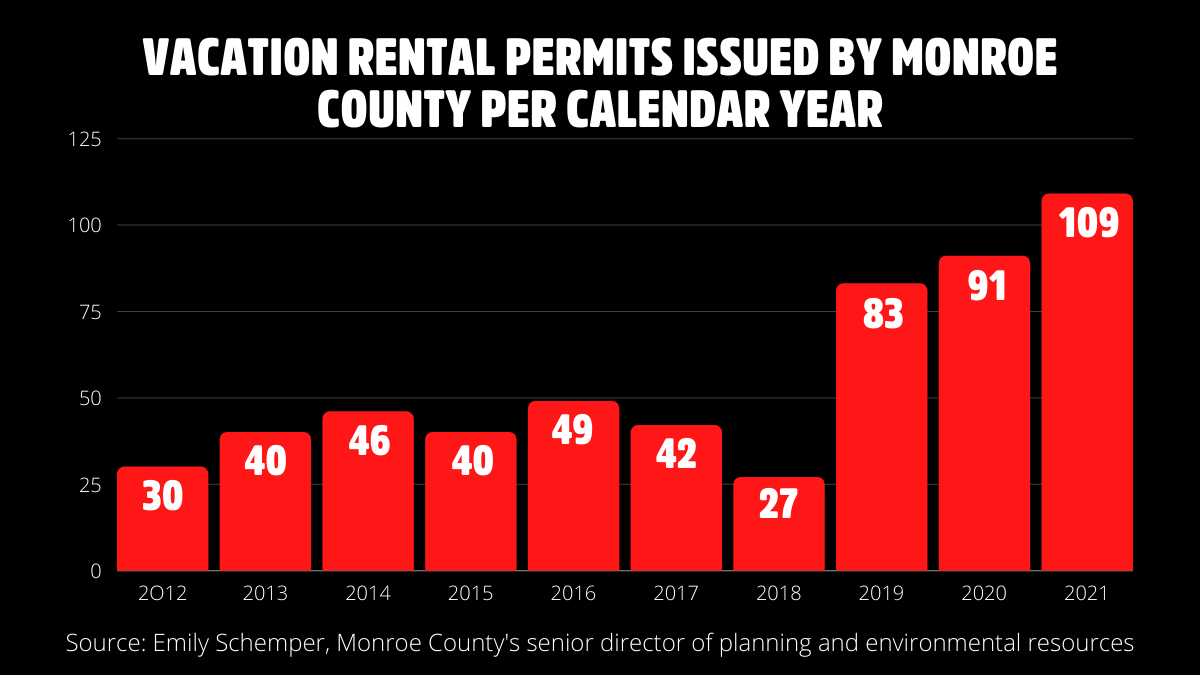

Vacation rentals are a common target of finger-pointing for those who claim the Keys community is changing, to the point that calls for changes to local rules that would restrict these rentals are practically background noise. But in most cases, the power to enact change is blocked at the state level.

State statute 509.032(7)(b) prevents a local law from restricting the use of, prohibiting, or regulating the duration or frequency of rental of vacation rentals. Codes enacted before June 1, 2011 are “grandfathered in.”

But there’s a catch: any changes made to an existing ordinance instantly remove the grandfathering. Therefore, explained Monroe County attorney Bob Shillinger, counties and cities can’t pass laws to cap or further regulate vacation rental permits. “It’s not in the county’s power,” Shillinger said. “We’re grandfathered since 1997 with an ordinance. If we place a cap on it, we lose our grandfather status.”

“We have to fight every session to keep (our code),” said Islamorada councilman David Webb. “The legislature has made it clear that if the village attempts to modify it in any way, it will be null and void totally.”

Cities aren’t just fighting a losing battle to take back control of their own ordinances. Campaign contributions from the deep pockets of companies like AirBNB and VRBO regularly put municipalities on defense. “There’s almost constantly a bill at the state each year that would eliminate what we’ve got, rather than change it or make it better,” said Marathon city manager George Garrett.

Just one example: although many cities charge a fee of $1,000 or more to register a vacation rental, providing a significant stream of revenue, Senate Bill 512 could strike a blow to the funds. If approved, the bill could prevent local governments from charging more than $50 (if anything) to process an individual application. In Islamorada, annual licensing fees total $1,325. That’s less than the village Achievable Housing Advisory Committee’s recommendation of $2,500 with an additional fee of $500 for units with more than two bedrooms.

The state bill appears dead, however. Session in Tallahassee concludes on Friday, March 11.

But some changes could be possible without state interference if the city’s or county’s leadership “steps up and gets creative,” said Scott Pridgen, executive director of AH Monroe, a nonprofit dedicated to increasing access to affordable housing and health care in Monroe County. AH Monroe has built more than 100 units of affordable housing in Key West and is part of The Lofts of Bahama Village group that’s building more than 100 units of rental and owned homes at the city-owned Truman Waterfront.

“Let’s not make it so easy to make a bunch of money with these properties,” Pridgen said. “It may not be a popular move, but we as a city need to make it more difficult and more expensive, because we simply don’t have the housing inventory to support our workforce. Make the property taxes and licensing fees so high on AirBnBs and vacation rentals that it’s a less attractive option.”

NO BLAME FOR THE VACATION RENTAL GAME

It’s no surprise vacation rentals in an idyllic island chain are a profitable business venture, particularly in the wake of a global pandemic that saw Florida minimize business closures and promote tourism relative to other states. Individuals can’t be faulted for wanting to maximize the return on their investment in a perfectly legal manner.

“A guy can do vacation rentals of his place in Old Town Key West for four months a year and make all the money that he would make for a 12-month lease,” said Sam Holland, who chairs Key West’s planning board and owns the popular Conch House guesthouse.

The same holds true in Marathon. Imagine a four-bedroom house commanding $5,000 per month in rent. Contrast that house with one of the few four-bedroom vacation rentals available as of press time during 2022’s lobster mini-season. The price tag for a single week: $12,300.

Governments and real estate agents are aware of the rentals’ proliferation. “One of the very first questions we were asked as Realtors when people start researching the Key West housing market is, ‘Can I AirBnB this?’ Like the word ‘Xerox,’ AirBnB has become a verb,” said Key West native and Realtor Bascom Grooms, who owns Bascom Grooms Real Estate.

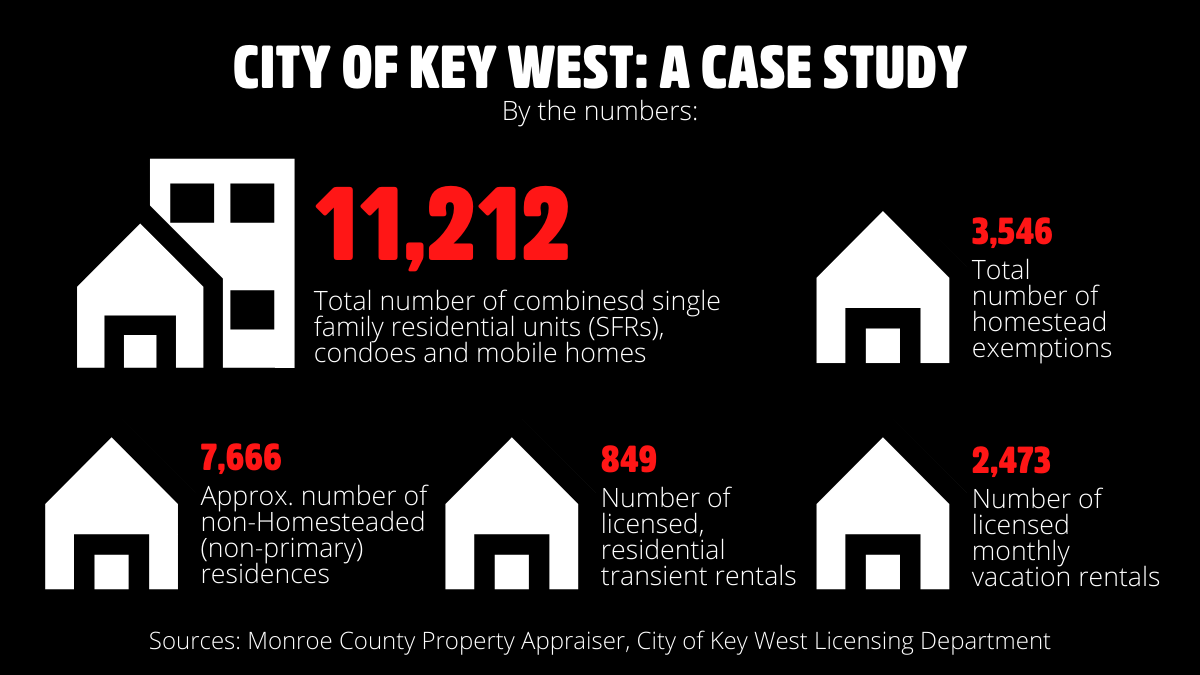

In Key West, the number of transient licenses, which are required for rentals of fewer than 28 days, was capped more than a decade ago, and the city enacted zoning restrictions that moved short-term rental properties out of residential neighborhoods. No new short-term licenses are being issued, and a property owner must buy an existing transient license, Grooms said, adding that the going rate for a transient license in Key West is about $250,000 to $275,000, but they’re rarely available for sale.

But almost anyone can turn their Key West property into a monthly vacation rental. There’s no cap on those licenses, and no zoning requirements that restrict where they can be located. The city of Key West charges $21 per unit per year for a non-transient rental license, said Amanda Brady, Key West’s licensing director.

Mallory Pinto is in a uniquely well-rounded position in the Middle Keys: she serves on Marathon’s planning commission, is a real estate agent for Ocean Sotheby’s International Realty, and manages both short and long-term rental properties. And while she says her customers are evenly split among full-time residents, investors and “countdown” buyers who look to rent a property until they make it their eventual home, she stays conscious of community dynamics when categorizing properties for potential buyers who get “a little crazy” about vacation rentals.

“Our local government cannot limit the number of vacation rentals, but local management companies can choose to not represent those properties as vacation homes and push for long-term leases,” said Pinto. “Part of the sales and property management process down here is education and managing expectations. I take the time to explain why a property wouldn’t be desirable as a vacation rental and that it should stay as long-term housing for our locals. We are turning away homes that don’t fit the vacation rental mold, but also trying to educate those buyers about what the best use of the home is and the dire need for long-term rental properties in our community.”

Marathon planning director Brian Shea said the city has definitely seen an uptick in vacation rentals, but not in the ways that some believe. “It’s not affordable housing being turned into vacation rentals,” he said. “Of the people going through the building permit allocation system, only about 20-25% become vacation rentals. A lot of rentals are built as replacement buildings after something else gets demolished.”

And as building allocations in the Keys rapidly dwindle, cities see the same “swap” over and over again: a potential long-term housing option for working individuals or families is sold or demolished, and either the transferable building right is used in another location or a vacation rental claims the site.

EMPTY HOMES

Marathon Realtor Josh Mothner does believe the vacation rental situation has affected the city’s quality of life, but isn’t as quick to peg it as the main culprit for the affordable housing crisis in the city.

“Other parts of the Keys don’t have vacation rentals, and they still have a problem,” said Mothner. “I think it’s incredibly important to look at the number of second homes that may not be used for months out of the year. They take up needed housing as well.”

Islamorada resident Jim Doran moved to the Keys from South Florida in the late 1970s. A retired Key Largo School teacher, Doran is vice president of the homeowners association at Venetian Shores in Islamorada. There were only a quarter of the houses that stand today when he arrived several decades ago. Doran said Venetian Shores still has community with people who live year-round, but he’s seeing homes sitting vacant most of the year.

“They might be here for the winter or they might be here for a couple weeks, or they’re rentals,” Doran said. “But we don’t know the people at all. Some of the issues we have with them is they don’t have ownership in Venetian Shores.”

Part-time residents and absentee owners have varying degrees of connection to their local Keys communities. Some are involved and care deeply about the same issues as full-time residents, and many of the “countdown” owners Pinto described intend to make the Keys their full-time community eventually, using rentals during parts of the year to pay off mortgages and speed up the relocation process. On the other end, the extent of some owners’ involvement is the cash they throw sight unseen at investment properties.

“The biggest threat in this community is so many second and third homeowners who don’t live here, and only spend a month or two here a year,” said Holland, the Key West planning board chair. “Why wouldn’t they rent the place out monthly the rest of the time? They hire a property management company, or now there’s even virtual innkeeper services that further reduces labor costs. The owners don’t need full-time staff on the property. The people get a key and are on their own. The owner sits back and collects a check every month.”

NOT IN MY BACKYARD (NIMBY)

Few would openly oppose affordable housing solutions for the Keys’ workforce. But a tiny island chain has limited land, and when these solutions involve developing areas just next door, or a few feet away, even full-time Keys residents change their tune, and workforce housing developments can face fierce opposition.

How often have residents heard some version of the following sentences: “I support affordable housing 100%. But our neighborhood already suffers from (traffic congestion/ overcrowding/ limited parking). This just isn’t the right location for it.”

A recent post on a Marathon community Facebook page perfectly summarizes the “NIMBY” sentiment. “I want to let everyone know what is going on with properties in Marathon,” the post reads. “We have an empty double lot by me, and we just got a notice for a variance. … Seems it will be affordable housing, which I am not against, but instead of one unit on each lot, they are going to squeeze in two on each. … So sad they are cramming houses together. Really is ruining the neighborhoods.”

Many city and county officials have come to understand that the Keys’ previous density and height restrictions make the additional affordable housing next to impossible. In Key West, measures have been proposed to increase the allowable height and density for developments in which at least 70% of the units are affordable. Such easing of restrictions would enable apartments to be built atop the island’s three main shopping plazas along North Roosevelt Boulevard and in other areas of town.

EFFECTIVE ENFORCEMENT

Finally, not all rental property owners play by the rules. On the contrary, a number of property owners simply view fines for illegal rentals or code violations as a cost of doing business. And once again, state statutes oppose the efforts of county and city officials. Under Florida statute 162.09, a first-time code violation in municipalities with populations less than 50,000 carries a maximum fine of $250 per day, while repeat violations carry a $500 per day price tag and an “irreparable or irreversible” violation can run up to $5,000.

In Marathon, the month of February saw a total of 16 code cases opened across all categories of violations. “The point is that you have to make it painful to break the rules,” said Marathon Realtor Josh Mothner. “Right now, it’s not.”

Key West Code Compliance Director Jim Young told the Keys Weekly his department had 55 complaints of illegal rentals in 2021. “And the new rule that says complainants can’t be anonymous has not affected those numbers at all. People are absolutely willing to turn in suspected illegal rentals.”

Larry Fox is a homeowner in Big Pine Key’s Eden Pines neighborhood, where he says illegal rentals are taking over. “There are currently seven Eden Pines homeowners who have been collecting information related to our concern about so many illegal short-term rentals in our immediate vicinity,” he said. “Commissioner Michelle Coldiron referred us to Cynthia McPherson in the county’s code enforcement office and we have provided her with documentation and photographs regarding the known illegal short-term rentals, but we don’t know where or how we can help from this point on. … What can we do from this point to stop this craziness?”

Before an owner can be fined or held accountable for tax penalties for properties not legally registered as vacation rentals, they must be effectively caught in the act. And investigations into unlicensed vacation rentals and AirBnBs, whether rented short-term or monthly, are tricky, time-consuming and costly.

Though proper tax collection is arduous, it remains a top priority for Monroe County Tax Collector Sam Steele. Steele said his staff does go through vacation rental apps such as VRBO and AirBNB to look for noncompliant properties that have not taken out tax receipt accounts. Once a property is verified as noncompliant, the owner receives a letter from his office. Eventually, enforcement gets tough. “We have filed a total of 344 tax warrants and have issued 34 bank freezes,” Steele said. “The number of tax warrants and bank freezes issued represents an individual action, whether it is a repeat on the same property or another property.”

Code enforcement fines, meanwhile, can accumulate in some areas to tens and hundreds of thousands of dollars in recent years as property owners repeatedly violate rental regulations and other codes. For decades, elected officials in Key West have allowed violators to pay only a fraction of the amount owed, and in some cases have waived the fines entirely. That trend may be changing, though, as Key West city commissioners earlier this month refused to accept an owner’s offer of $10,000 to clear up $570,000 in code enforcement fines. (Those fines were for unpermitted construction, not illegal rentals, but the commission’s refusal to accept the offer showed its frustration with meaningless penalties.)

“You have to have a strong deterrent. The real issue is enforcement, and a $500 fine just becomes a cost of doing business,” said Holland. “The money is so big, the fines right now are no deterrent.”