The stocky Russian with large hands named Nicholas Matcovich left Key West with his wife Eliza in 1868. He had reportedly been managing a nursery at the time but was unhappy living among the number of people adding to Key West’s growing population.

To escape, Mr. and Mrs. Matcovich moved 30 or 40 miles northeast to No Name Key. At 1,140 acres, it was less than half the size of Key West, and had a relatively small community.

In 1870, Key West had a population of 5,675 while No Name Key had only 45 – three of them were Matcovichs. Believe it or not, a population of 45 in 1870 was a pretty significant number for any island not named Key West. Outside of Key West, there were only 641 people documented living on the rest of the Florida Keys. Key Largo, the largest island in the chain, had a robust population of 61. Upper Matecumbe Key, today the heart and soul of Islamorada, had 13 residents. At 45, No Name Key had about the same number of people living on the island as it does today.

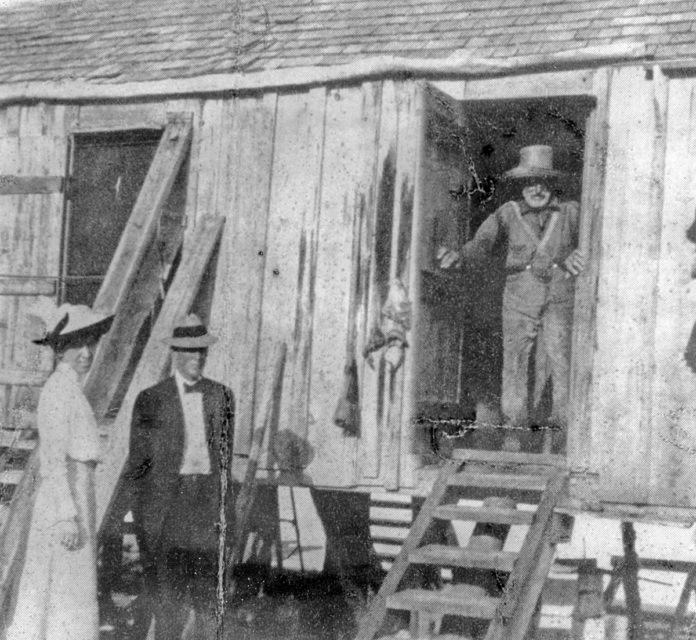

After arriving on No Name Key, Nicholas built a “home” for Eliza and their baby boy, George, who arrived circa 1869 (and home might be an extravagant word). The “house” he built was a one-room structure measuring 12 feet by 15 feet and was topped with a roof of palmetto fronds. When he first arrived on the island, he did what he could to make a dollar, including burning charcoal and planting coconuts on Big Pine Key that he later sold for five cents each.

Cramped quarters aside, by all indications, Nicholas grew to be a suspicious man, wary of those he did not know. He may have also been a hard man to live with because at some point in the early years of their marriage, around 1874, Eliza moved back to Key West, taking her children, and found work in a cigar factory to help support the family. Though the two remained married until Eliza’s death in 1917, for the last 43 years of their union, she lived in Key West while Nicholas stayed on No Name Key. Still, she would visit from time to time, and sometimes, during those visits, children were conceived. In addition to the oldest, George, six other children were born, including John, Anna, Mosby, and three others who were not long for the world.

For the majority of the rest of his life, Nicholas lived alone, like a hermit, and eventually turned to what he did best, growing things. By 1885, Matcovich was granted a 160-acre homestead where he grew to be something of an early expert in the field of Florida Keys horticulture and attracted the attention of William Krome, David Fairchild and the government.

Krome visited Matcovich’s land while working for Henry Flagler and building the right-of-way that delivered the Over-Sea Railroad to Key West in 1912. Krome was a horticulturist, too. By 1904, he had made an 80-acre homestead claim in the area of what is today Homestead, where he helped to develop Florida’s avocado and mango industry.

Krome and Matcovich developed a sort of friendship, and when times were lean for Nicholas, Krome is said to have sent packages of food to him. In 1912, Krome took noted horticulturist and namesake of Miami’s Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, David Fairchild, and his wife to meet Matcovich at No Name Key. The government, too, became interested in his farming and sent plant species to No Name Key so that he could experiment with sub-tropical growing techniques.

Reportedly, Matcovich was growing more than 5,000 trees on his land, including 50 species of fruit trees, including lemons, limes, figs, guavas, bananas, dates, peach, alligator pears (avocado), sapodilla, and even walnuts. He was also reported to be growing 20 varieties of grape vines. For freshwater, for himself and to help feed his plants, he created four wells about four feet wide and eight feet deep on his property by carving them out of the limestone substrate with a crowbar. He also scraped away steps leading down to the water.

The name Matcovich carried a warning with it, and anyone familiar with No Name Key knew to approach his corner of the island with caution. Rumors suggested that his property was booby-trapped with tripwires and shotguns. One of the details about his life on the island that was documented on more than one occasion was his fondness for guns, as he was repeatedly observed having “many” of them hanging on the walls of his one-room home with the palmetto roof.

At the edge of his property, he erected a “single plank that served as a wharf.” About 100 yards offshore, he pounded a stake into the bottom of the shallow water and tied a large horse conch shell to it. On shore, at his property line, he struck another stake into the ground and hung another horse conch shell that could be blown like a horn. On the stake, he left a sign that read, “Not one step farther, Nicholas.”

Whether or not he ever really did booby-trap his property is up for debate – it does make for a great story. Nicholas died on Aug. 14, 1919, just a month before the 1919 Florida Keys Hurricane wreaked its havoc on the Lower Keys. His son Mosby, however, would move to the family property and bring the threat of gunfire back to No Name Key – a story for next week.