One of the best early accounts of aboriginal life in the Florida Keys was in a memoir by Hernando De Escalante Fontaneda. As a boy, Fontaneda was shipwrecked on the Florida Keys and spent 17 years living with the Calusa Indians. His memoir was published in 1575.

In his work, he wrote about the Calusa: “The territory of Carlos, a province of Indians, which in their language signifies a fierce people, they are so-called for being brave and skillful, as in truth they are. They are masters of a large district of country.”

He also wrote about the Keys, noting: “On these islands is likewise a wood we call here palo para muchas cosas (the wood of many uses), well known to physicians; also much fruit of many sorts, which I will not enumerate, as, were I to attempt to do so, I should never finish. … These Indians have no gold, less silver, and less clothing. They go naked except only some breech-cloths woven of palm, with which the men cover themselves; the women do the like with certain grass that grows on trees. This grass looks like wool, although it is different from it.”

The “palo para muchas cosas” may have referred to the lignumvitae tree, which has a history of medicinal uses ranging from modern pharmaceuticals like Xanax to Viagra. For a long time, it was also used to treat syphilis. What I have always been curious about is the statement “also much fruit of many sorts, which I will not enumerate, as, were I to attempt to do so, I should never finish.”

What were the “fruits of many sorts” that Fontaneda observed? A quick search of plants native to the Florida Keys provides a surprisingly long list of scores of possibilities. The fruits of historical note that were not included on the list were pineapples, Key limes and coconuts — none of which are native to the Keys but were later introduced. Potential fruits and other edible plants that might have been among those observed by Fontaneda include berry, plum and cucumber, among others.

Quail berry, or Christmasberry, is an evergreen that bears small red berries year-round. The mildly sweet berry grows in pine rocklands and rockland hammocks. Cocoplum produces a purplish plum with a bland flavor. The seeds taste something like almonds and can be roasted or crushed and added to other dishes for extra flavor. Seagrape produces clusters of red grape-like fruits that ripen in summer.

Coral bean, sometimes called Cherokee bean, has both good and bad properties. Native Americans ate the roots to increase perspiration. The red flowers and young leaves can be cooked like string beans. However, parts of the plant are toxic, a narcotic and a hallucinogen.

The creeping cucumber’s fruit is about the size of a jellybean. It is edible when it is ripening and still green with white stripes, like a tiny watermelon. Once it continues to ripen and turns purple to blackish, it can become toxic.

The coastal ground cherry is also edible. The yellow to orange berries are covered in a papery husk like a small tomatillo.

The Florida prickly pear cactus, sometimes called the devil’s tongue, produces a reddish fruit that grows atop the cactus’ flat paddle. Once de-thorned, both the fruit and the paddle can be eaten. The fruit can be eaten raw, but the paddle is best grilled or sautéed. The paddle is sometimes found in the produce section of the local supermarket.

The gopher apple is a small fruit that grows from ½ inch to 1 inch in length and ripens in late summer. As the fruit matures, it transitions from white to a pink, purple or red color. The flavor has been reported as relatively tasteless.

Marlberry fruits grow off and on throughout the year. When the small berries first grow, they are green or reddish but turn a shiny black color when they ripen. Some people report the flavor as something like blackberry or a grape, though not everyone seems to agree, with some referring to the fruit as distasteful and acidic.

The beach bean, sometimes called seaside bean or bay bean, grows near the water’s edge and develops tough bean pods about 3 inches long and 1 inch wide. The plant’s flowers can be eaten, and the pods, when they are still young, are edible when boiled or roasted. However, as the pod matures and grows thicker, the beach bean can be toxic.

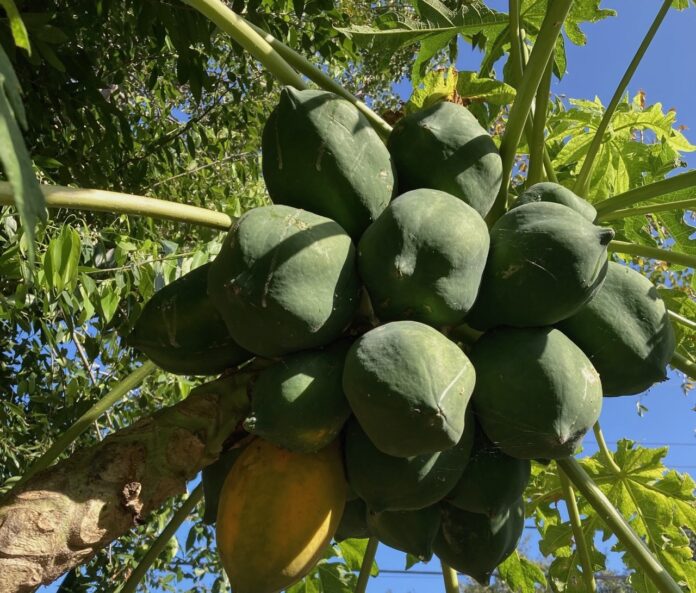

One of the more recognizable fruits that Fontaneda might have observed and possibly tasted was what early Keys pioneers called pawpaw. The more common name is papaya, and though not indigenous to South Florida and the Keys, it is considered a native species. Native species that are not indigenous need to have arrived before European discovery. Several years ago, papaya seeds dating back to circa 300 A.D. were discovered in Lee County. By the time Fontaneda was shipwrecked in the Keys, the papaya had been growing in Florida for more than 1,200 years.

The ripe fruit of the papaya is soft and juicy, with some comparing the flavor to a mango. I would disagree, as I find a mango delicious, though messy. I find papaya to be more like the mixed reviews of the marlberry that is sometimes likened to the taste of blackberry, and some not liking it all. While the historical note attached to the papaya’s story is super cool and I love that part of its history, I do not care for the taste of its fruit.